Sometimes, when it comes to depicting the period of the British Mandate, Jerusalem gets it wrong. Take, for example, the Pillbox, the cylindrical cement outpost at the junction of Tchernichovsky and Azza streets, currently decorated with images of red-coated, bearskin-helmeted Queen’s Grenadier Guardsmen. Historically inaccurate and just plain wrong.

But when Jerusalem gets it right, it is spectacularly so.

A new experiential exhibition at the Tower of David Museum, “London In Jerusalem: Culture on The Streets of The City 1918-1948,” brings to life the brief but critical 30-year period when, under British rule, Jerusalem was transformed from a sleepy Ottoman backwater into a modernized city whose vibrant cultural activity was shared by Brits, Arabs and Jews.

The exhibit recreates several important cultural touchstones: living room teatime soirées, Mandate-era cinema complete with daily movie screenings, radio broadcasts, and a reconstruction of the legendary Fink’s Bar with original furnishings — all to give visitors a chance to experience the sights and sounds of everyday life in Jerusalem of the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s.

Although a mere moment in the history of this ancient city, the period between December 11, 1917, when General Edmund Allenby entered the Jaffa Gate, and May 14, 1948, changed Jerusalem for the ages.

According to exhibit curators Liat Margalit and Inbar Dror-Lax, “By establishing Jerusalem as the administrative center of Mandatory Palestine, the British gave the city a status it did not have during Ottoman rule… Jerusalem enjoyed financial and cultural prosperity and the city’s population grew.”

In 1918, the city’s first British governor, Sir Ronald Storrs, established a public committee aimed at the “rehabilitation and preservation of the historical heritage of the city, encouragement of arts and handicrafts, and support of local artists.”

Storrs took on a major project: to restore the citadel known as the Tower of David and convert it from a military fortress into a cultural center. In 1921, the Tower of David hosted its first concert, and in 1923, its first exhibition: paintings by artist Reuven Rubin.

In the late 1920s, a wave of middle-class immigrants – mainly European Jews escaping persecution and Arabs from what had been the Ottoman Empire — joined the city’s Muslim, Christian and Jewish populations. This influx, the curators say, “introduced new spices into the melting pot that was Jerusalem.”

Under British patronage, the city’s residents were able to enjoy cultural innovations like restaurants, cafes and pubs, movie theaters, art exhibitions and galleries, concerts and sports activities such as tennis, bowling, cricket and polo.

By the 1930s, Jerusalem’s concert scene was in full swing, hosting artists ranging from tenor cantor Zevulun “Zavel” Kwartin, entertainer Josephine Baker, and Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum, to Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini.

The Jewish Artists Association, a group of young artists that rebelled against the Bezalel School style, held several group and solo exhibitions in the citadel between 1922 and 1927. Original posters advertising events in this “Tower of David Period” are included in the present exhibition.

As in any other city, Jerusalem formed its own version of a high society that held tea parties and dances. The exhibition includes a reconstructed living room typical of a 1930s Rehavia neighborhood, with original cabinets, china, radio and furniture.

In 1936, the words “This is Jerusalem calling” marked the first transmission of the Palestinian Broadcast Service. The PBS broadcasts in Arabic, English and Hebrew included news, live music, language lessons, radio plays, segments for children and youth, and morning calisthenics.

This British-controlled programming mix, the exhibition curators say, “played a significant role in fostering local culture.” A PBS studio installation allows visitors to listen to live recordings of Mandate-era radio shows.

The importance of cinema between the wars cannot be overstated and Jerusalem was no exception, with no less than 10 movie theaters operating by the end of the Mandate. The exhibition offers a glimpse into the movie-going experience with a tiny classic cinema installation where visitors can watch newsreels from early 1930s and 1940s, along with daily screenings of Tarzan and The Wizard of Oz – the most popular films of the day.

The exhibition has represented the era’s café culture by providing chairs and tables, like those of the famous Café Atara, each topped with an interactive educational kiosk to provide more in-depth information.

The King David Hotel’s guest book from the Mandate period is also on display, signed by diplomats, politicians, world leaders, artists, movies stars and public figures.

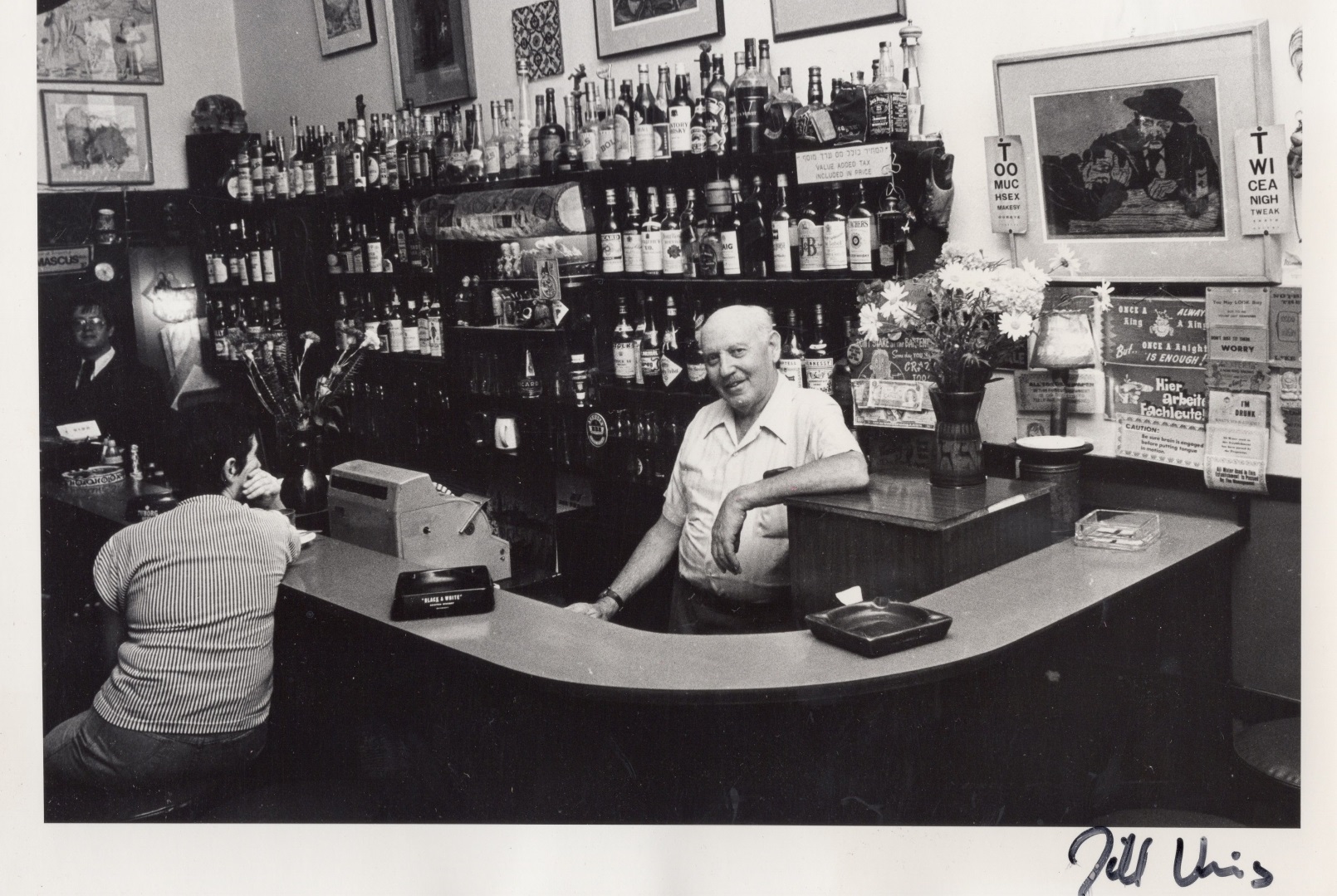

But perhaps the most emblematic of all Mandate-era establishments was Fink’s Bar and Restaurant, which continued serving up equal parts of whiskey, intrigue and goulash to officers, spies, politicians, journalists, artists and intellectuals from its establishment in 1932 on through its closure in 2005.

Curators Margalit and Dror-Lax were fortunate enough to discover that Fink’s original proprietors, Mouli and Edna Azrieli (daughter of the legendary owner David Rothschild), had saved most of the bar’s original furniture and decorations. Bottles, framed pictures, records, humidor and guest book are now on loan in an accurate reconstruction within the Tower of David’s Crusader Hall.

For more information, click here

“London In Jerusalem: Culture on The Streets of The City 1918-1948” runs concurrently with “A General and A Gentleman – Allenby at the Gates of Jerusalem” about the dramatic events that unfolded during the week of December 11, 1917, marking the beginning of a new era for Jerusalem. Both exhibitions are open until December 2018.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)