“There’s magic here. If you want to dance, you can find someone to dance with. If you want to make music, you can find that, too.”

Not many towns in Israel appear in popular songs, but Pardes Hanna-Karkur is one of them. Ehud Banai sings about the town’s “eternal bliss” in “Canaanite Blues,” while Hanan Ben Ari’s song “Pardes Hanna” touts it as a good place for raising children.

According to many of its 43,000 residents, Pardes Hanna-Karkur has a special charm, an artistic feel and a down-to-earth quality.

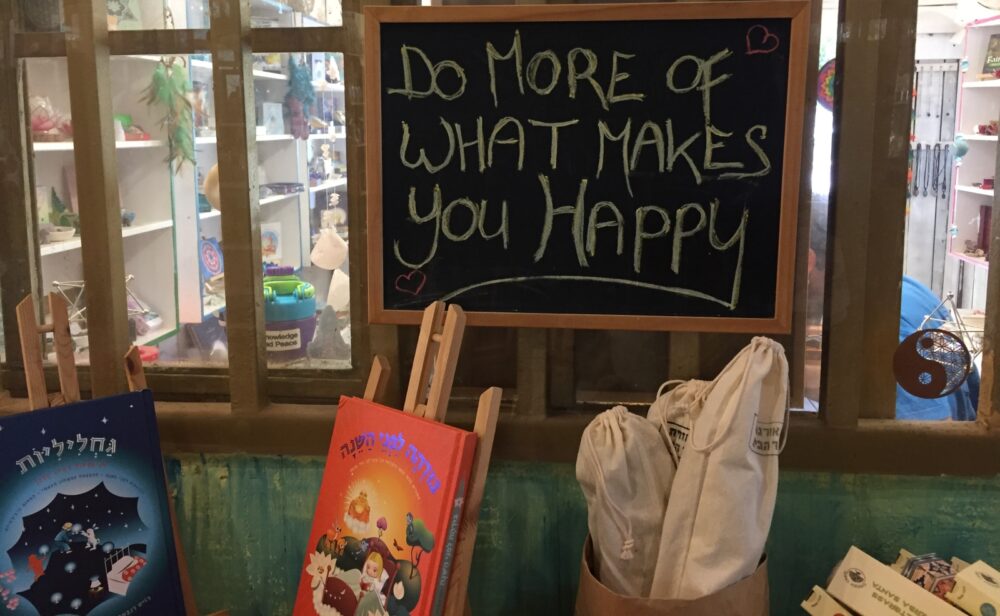

“I could live anywhere in the world, but I chose to live in Pardes Hanna-Karkur,” said Miri Tal, owner of Tatanka, a shop that sells colorful leather shoes, jewelry and accessories in what’s known as The Artists’ Stables.

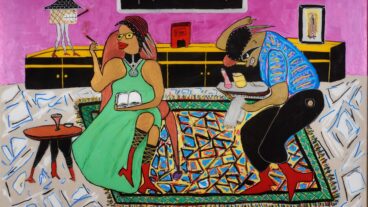

The stables used to house horses; now they are home to artists’ boutiques, cafes, restaurants and even spaces for therapists.

“There’s magic here,” Tal said. “There’s spiritual community and lots of love. If you want to dance, you can find someone to dance with. If you want to make music, you can find that, too.”

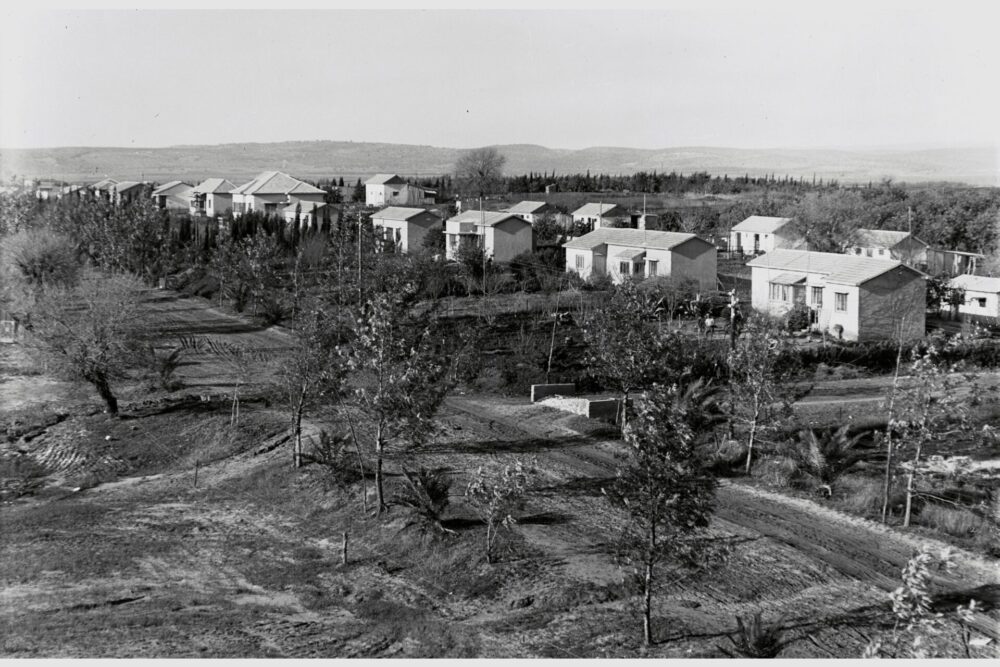

Situated in the Haifa district, Pardes Hanna-Karkur began in 1929, named after Hannah Rothschild, granddaughter of Nathan Rothschild of the banking dynasty. “Pardes” (pronounced par-dess) is Hebrew for orchard.

It joined with the village of Karkur in 1979 to become a joint municipality but it still has a small-town feel.

Though it’s become known for its hipster vibe, Pardes Hanna-Karkur manages to balance people looking for an alternative lifestyle with those who are traditional.

Visitors will find a variety of restaurants including Indian, Japanese and Italian, a high-quality delicatessen like HaMezaveh with overstuffed sandwiches, and coffee shops like Nuni veFortuna, which is packed with vintage clothes and tchotchkes.

There are shops selling wind chimes, homemade soaps, art, jewelry, handmade bathing suits and lingerie, and Hebrew calligraphy by the scribe Yaeer Suissa.

Alternative milk

Yael Or-Shalom, who teaches yoga when she isn’t working for a high-tech company, said her local grocery store owner accommodates the range of shoppers.

“He told me that he can tell what a customer is like just by the milk they buy,” Or-Shalom said. “When I bought rice milk, he said, ‘Oh, you’re getting alternative milk? Then you won’t take a plastic bag.’ And when I bought spelt flour, he said, ‘You definitely don’t want a plastic bag.’”

The town is known for attracting hundreds of artists, Tel Avivians looking to get out of the city, as well as Ethiopians and long-timers like Rina Radai, now 80.

She and her husband, who worked as a welder, raised nine children on their farm in Pardes Hanna along with sheep; they grew pecan, lemon and orange trees. Today, only the egg-laying chickens remain along with stray cats who, said neighbor Tomer Shimshoni, “like to think they’re chickens.”

Radai, who was born in Yemen, came to Israel when she was eight. Her family lived in a tent and a chicken coop for a while “because there were no houses.”

After she and her husband married and moved to Pardes Hanna, “it was quiet, we knew everybody, we used to leave our houses open and never had to lock our doors. There were orchards everywhere.”

As with everywhere else in Israel, orchards and fields are giving way to apartments. On a tour through the neighborhood, Shimshoni pointed out decades-old four-story apartment buildings; behind them, there are high-rise apartments built recently for another influx of residents.

Juggling in Pardes Hanna

Guy Lev, a web designer who is also a juggler, moved to the area 20 years ago. What drew him was the choice of schools, and then “I found myself in the midst of a dynamic community of artists.”

Lev is one of the leaders of Shikshuk, a popular open market that ran the first Friday of every month until Covid interrupted it; Shikshuk will start again in September. It operates on several principles, Lev explained: “You can only sell what you make or what you got secondhand and there should be ‘community-friendly’ prices.”

Lev also is involved in Festival HaNadiv (hanadiv, “the benefactor,” refers to Baron Rothschild), which will be held this year November 10-12. All the events are free, and anyone can create an event.

“That’s our way to broaden the meaning of culture,” he said. “People can organize an event that revolves around theater, food, arts, music, or they can give a lecture.”

He said the idea is not to “bring the show to people; we want people to be part of the show.” Lev created an app that connects people who want to lead an event, and those who offer their homes as hosts.

People who grew up in Pardes Hanna-Karkur often go away for a while and then return, such as Avner Vaknin. His father had a carpentry shop; after he passed away, Vaknin returned to take over the shop and add his own artistic touch.

“There have been a lot of changes since I was little but there are still the trees, the sea is nearby and the people are amazing,” Vaknin said. “I love it.”