Positive expectations improve the effectiveness of the immune system.

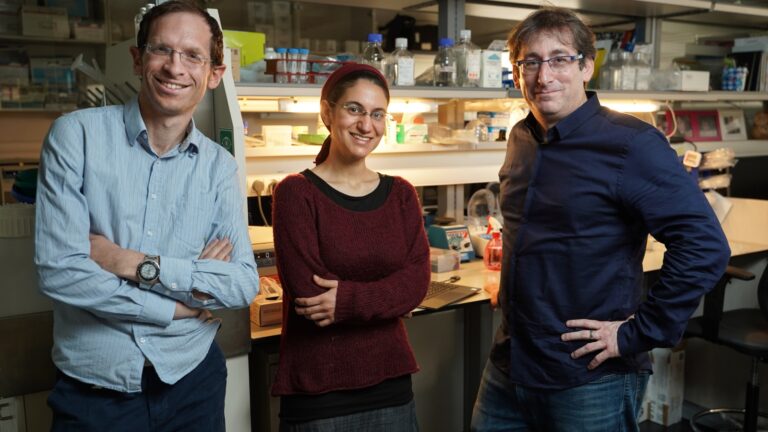

That is the conclusion of a study by Israeli researchers published July 4 in Nature Medicine.

Although the effect of one’s mood and attitude on the immune system is well documented – including the “placebo effect” in which patients feel better after taking a sham medication — this study suggests a specific mechanism of action of the placebo effect.

The findings potentially could lead to the development of new drugs that utilize the brain’s ability to cure through positive messages.

“Our findings indicate that activation of areas of the brain associated with positive expectations can affect how the body copes with diseases,” explained lead author Asya Rolls, assistant professor of immunology at the medical school of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa.

“Placebo is a complex phenomenon in which the patient’s expectation of recovery affects his state of health,” she continued. “Expectation of improvement and arousal of positive emotions are reflected in the activity of neurons in the brain. So we decided to understand, at the molecular level, how areas of the brain associated with positive expectations affect the functioning of the immune system – the body’s main defense system.

“Understanding the mechanisms connecting the brain to the immune system could lead to significant medical applications that can potentially improve the prognosis of diseases.”

Reward system

The research, carried out by doctoral student Tamar Ben-Shaanan, examined the effect of the “reward system” — a brain region triggered in anticipation of a positive experience, and stimulated during the placebo effect.

Using innovative technology, the researchers triggered the reward system in the brains of mice and examined the behavior of the immune system following this intervention. They found that the immune system operated more effectively and eliminated bacteria more quickly. And it caused the immune system to create a more robust memory against the bacteria to which it was exposed so that it could be more effective in future exposures.

“Our breakthrough was made possible thanks to two new technologies,” explained the paper’s other lead author, Assistant Professor Shai Shen-Orr. “One is DREADD (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) technology, which enables precise activation of specific neurons, and the second is CyTOF (mass cytometry) technology, which enables high-resolution characterization of hundreds of thousands of cells in the immune system.

“By coupling these two technologies, we were able to demonstrate the connection between the activation of specific neural circuits in the brain and the increased activity of cell populations in the immune system.”

Only the beginning

The researchers also mapped the sympathetic nervous system, through which messages are passed from the brain to the immune system.

According to Rolls, other pathways and hormones may also be involved in this interaction between the brain’s “reward system” and the immune system.

“This is only the beginning,” she said. “It is important to remember that these experiments were done in mice, and that it will be some time until we can translate this to humans.”

In conclusion, she said, “We know that our mental and emotional state impacts our health but in order to be able to use this potential of the brain to cure in modern medicine, we need to understand how it works. Understanding that activation of the reward system in the brain triggers the immune system will allow us to optimize existing therapies against infections and boost the effectiveness of vaccines.”

In a study published last year, Rolls revealed that a good night’s sleep boosts the success of bone-marrow transplants.