When Apple introduced Face ID with the iPhone X in 2017, it was meant to make opening your phone faster and more secure. That’s not how Gil Perry sees it. Face recognition, he says, is “now a threat to the fundamental human right of privacy.”

What’s so alarming to Perry? Photos, like passwords, can be hacked. Advances in face-recognition algorithms, in the wrong hands, can allow bad guys easy access to your personal data.

And unlike an easily updated password, “you can’t change your face or leave it at home,” Perry points out. Nor can you delete all your photos from the Internet. Pictures of you that are posted online, whether by you or by someone else such as your employer, can never fully be scrubbed from the web.

Generally, that makes it easier to function in the digital age. Biometric passports, for example, allow faster passage at border control.

Perry founded D-ID in 2017 to prevent the other scenario, the one where photos are used unscrupulously. The company’s software – D-ID is short for “de-identification” – subtly alters a photo in ways that fool face-recognition algorithms without changing how the image appears to human eyes.

In that way, your photo can still appear on the company directory without making you vulnerable the next time you tap your profile picture to log into Facebook.

D-ID’s technology, says Perry, was the first one able to confuse the machine without ruining the photo by pixelating or blurring images. The changes are sometimes as nuanced as increasing the distance between a person’s eyes in the picture.

“The algorithms will be looking for a close or exact match. Human viewers won’t notice the difference,” Perry tells ISRAEL21c.

Still, the de-identification process needs to be generalized “since we don’t know exactly what the algorithms will be looking at each time.”

FindFace fiasco

The most infamous example of how face identification can breech privacy involved NtechLab’s controversial FindFace app that could track people on VKontakte, Russia’s equivalent to Facebook.

A Russian photographer demonstrated how the app could blast past privacy restrictions and posted the results as part of a project dubbed “Your Face is Big Data,” claiming that software like FindFace “could be used by a serial killer or a collector trying to hunt down a debtor.”

In 2016, FindFace generated even more controversy when it was used to de-anonymize Russian pornography actresses and alleged prostitutes. The consumer-facing site has since been shut down but FindFace has found a new niche providing face recognition software to governments, banks, retail stores and casinos.

The growth of advanced face-recognition software and the cloud connecting everything everywhere has made the issue of cameras capturing our images on the streets, in buildings and stores without our knowledge particularly acute now.

“Anyone with access to a database of photos can track you wherever you go, sometimes hack your device and even steal your identity,” Perry says. “We prevent against that.”

Introduced at TechCrunch Disrupt

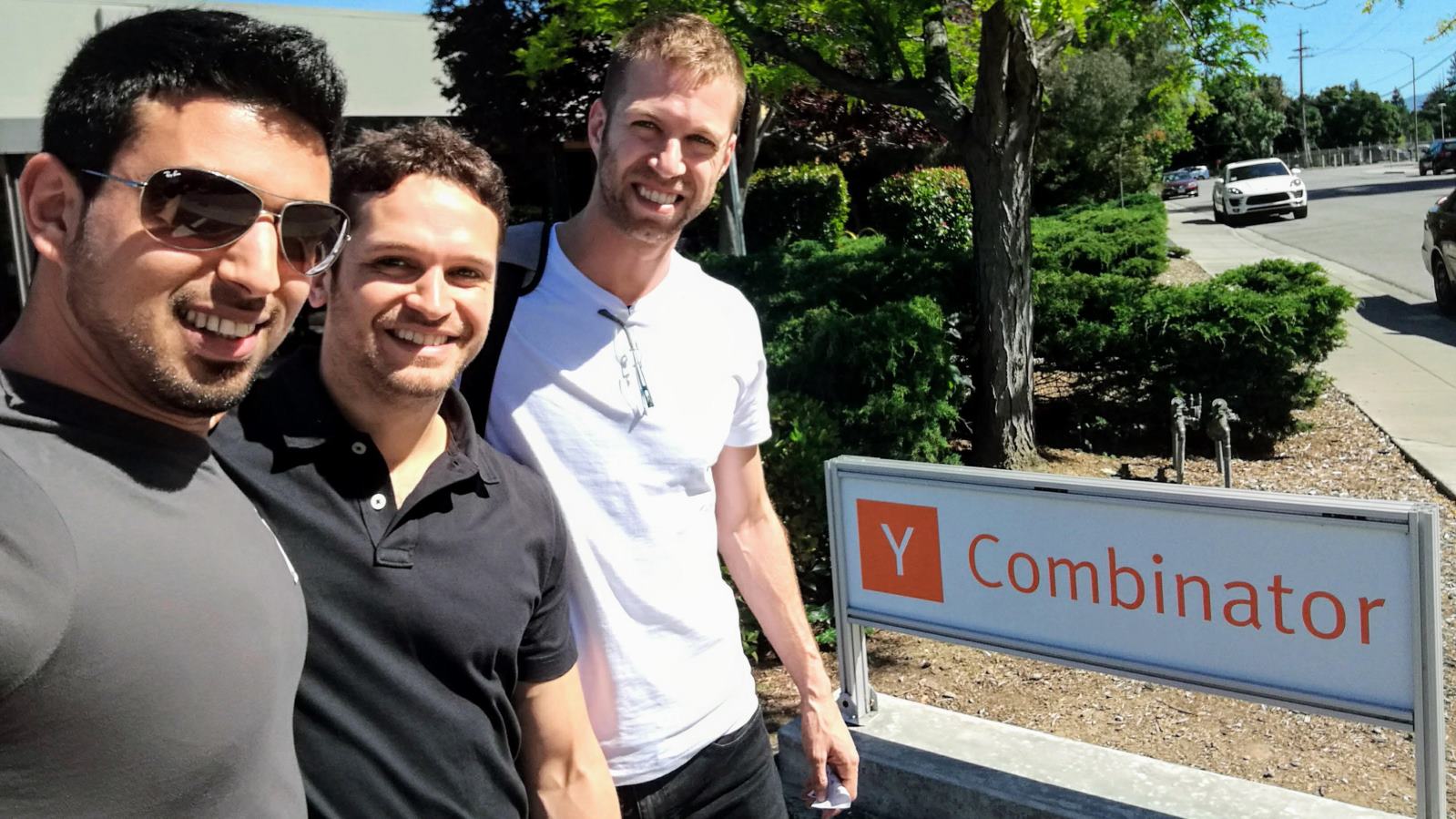

D-ID was incorporated in 2017, but Perry and his partners – COO Sella Blondheim and CTO Eliran Kuta – have been working on the concept for a half dozen years.

They came up with the idea while on a post-army trip to South America. They had served in the IDF’s 8200 intelligence unit and were prohibited from sharing photos online due to the sensitivity of their previous military positions.

“Everyone else was taking photos and uploading them. We like to socialize, too,” Perry recalls. “So we started researching. This was before face recognition was being used, before deep-learning algorithms were being integrated, when the identification wasn’t yet so accurate.”

The company formally launched its product at September’s TechCrunch Disrupt conference and already has “one big customer and commercial agreements with top players in the cloud image storage market,” Perry says, without revealing specifics.

Of the company’s 17 Tel Aviv-based staff members, five have PhDs in subjects ranging from data science to artificial intelligence.

In January, D-ID raised $4 million in a seed round led by Pitango Venture Capital with participation from US-based Y Combinator seed accelerator.

If you now share Perry’s alarm and want to buy privacy protection from D-ID, you’ll have to wait. “We don’t protect consumers – for now,” Perry says.

He realized D-ID could have a greater impact by courting the big organizations that store your photos, whether that’s government, a phone manufacturer or a social network. “If demand grows from consumers, we’ll give it to them as well,” Perry promises.

Carmakers are also shaping up to be key D-ID customers. “Autonomous vehicles capture photos of pedestrians without their consent,” Perry explains. “They need these photos in case something happens,” but the companies also want to avoid compromising an unsuspecting sidewalk stroller’s privacy.

With new data scandals being uncovered daily, online privacy has long since been a fringe topic limited to cybersecurity geeks. It’s also at the heart of the European General Data Privacy Regulation (GDPR) that went into effect in May. That’s given a significant boost to D-ID’s public profile.

In life, love and face-recognition software, it seems, timing can be everything.