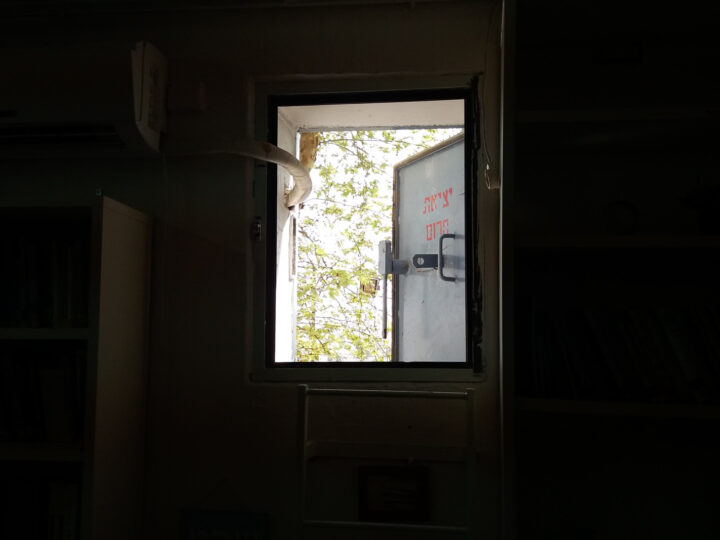

“The door is locked,” I say out loud to myself, looking at my apartment door in Athens, Greece around 6am on Friday, October 6. I repeat it as I check my pockets (wallet, headphones, phone, keys, inhaler, repeat).

I say again out loud in Hebrew, naool – LOCKED — and proceed down the stairs.

If I don’t perform this little ceremony aloud, I might have to go back up, and I can’t. I’m on the way to the airport, later than planned as usual, fueled by lack of sleep and anxiety. I’m going home.

Where is home? I asked myself on October 5, the night before returning to Israel, to a place I haven’t lived for a few years. Who cares where home technically is? Falafel, here I come.

For the past five years, I’ve been calling Athens, Greece, home. Whenever visiting Israel, after a few days of the humidity and prices, I am usually ready to go home.

So where is home?

In the airport, I get a Greek coffee, do a quick check-in, a seatbelt, a nap and two hours later, I’m in Tel Aviv.

My body is first shocked by the immediate, eminent presence of summer in October. I sweat my way to the Hagana train station and walk over to my friend Hila’s place.

My little sister soon arrives, then later returns with food (Iraqi kibbeh and rice) and I spend the afternoon with her, then a bit with Hila, who will later go to Haifa, and should be back on Sunday.

As for me, a disco nap, and then I will head out as planned to a 90s party at the Barby, a legendary Tel Aviv live music club where I spent many hours at shows, when this was home. I already have tickets for the final December shows there before it moves to a new location.

I could sleep through World World III

Not having slept the night before, under emotional jet lag and that surreal feeling of being back and continuing a conversation with the city, the country, as if you never left, my disco nap before the party turns into deep sleep.

The next thing I remember is war.

I always said I could sleep through a missile attack, having done so for three years while being a student in Sderot and having lived through the Gulf War as a child. If you need PTSD — as Sebastian says in The Little Mermaid — I’ve got plenty.

I did not wake up at 6:29 when bloodthirsty monsters broke through the fence, but at some point I did wake up from my internal clock buzzing combined with light and the increasing sounds of notifications pouring in. Eleven unanswered calls. Half asleep, I call Hila first.

“How are you still sleeping?” she says, “there’s an attack, look at the news. Hamas.” I call my sister. She can barely speak. “Did you hear?” she finally says.

“Hear WHAT?”

Your worst fears come to life

The next days are a blur of sirens and the sound of bombs hitting the ground, not too close but definitely not far enough.

But mostly — terror. Not ketchup film horror you can click away, but real, live-action terror, gut-turning, heartbreaking, nerve-tearing, up-your-spine-crawling type of terror.

We all grow up too soon in Israel, confronting horrors as we’re being taught at very early ages of our history. They save the harder imagery for fourth- to sixth-graders, but you know even before. No one stops you from finding the visual truth of it all, at the school library.

I vividly remember in first grade, on Holocaust Memorial Day, the teacher put us in the middle of the room, built a “ghetto” of chairs around us, and told us to imagine how Jewish children felt during that period. You know, when they and their parents were burned alive.

I had nightmares about that chair ghetto for years after that. That image and feeling still comes back to me sometimes — more so over the past days. The creeping horror after reading about fedayeen terrorist murderers infiltrating Nahariya when you were a child living up north, the pogroms in Europe you learn of around the same time you get your first Disney videotapes.

Your worst fears have now come to life and despite knowing your horrid history, it’s worse than you could ever imagine.

Collective fear

Walking down empty Tel Aviv streets, it feels a bit like the 1990s when taking a bus could cost your limbs or life.

Had I been in Greece when the gates of hell opened, I would be devastated but it would not be the same. There’s nothing in the world that could make you understand unless you’re there, unless you see the look in people’s eyes, taste the air as the windows shake, smell the collective fear in the air.

In Israel, we say, “Zar lo yavin,” a stranger would not understand.

I can’t stop thinking that if this is how I feel only being under missile and psychological attack, how do the people feel who survived death in the outskirts, in places where some of the best years of my life occurred? How can they stand to even be conscious right now?

My flight, of course, got canceled. I threw myself into work, calming down my friend and my sister as best as I could, even cooking for Hila a few days after, not allowing more than crumbs of reality infiltrate me. I was naturally and quickly in full survival mode.

I’m not okay

Seeing I’m not back, friends from Greece contact me to check what’s up. I say I’m okay but I realize I’m lying.

I try not to read or see certain pictures and words so they don’t fuel my anxiety even more, but the bits I did see and hear are already there, and the mind vividly completes the rest.

I’ve been here for days and still haven’t had falafel. This alone should signify the severity of events.

My new flight is finally scheduled for Friday, three days after my cancellation. I focus on technical things that need to happen: blood tests, grocery shopping, when do I need to get to the airport, what did I forget to pack.

On Friday at the airport, I realize I’ve left my phone in Tel Aviv. Is part of me trying to miss the second flight on purpose?

I go get it, frantic, and strangers try to calm me on the train. I get back in time to the messiest, busiest version of Ben-Gurion Airport that I’ve seen in my life. The security lines are insane, but somehow it ends on a plane.

Everything is quiet on the plane, it’s not even packed — as if we are not escaping a warzone. I go back to get my own row.

The Cypriot crewmembers are smiling but there’s no smile in their eyes. They seem tired and sad as they look at us. I try to sleep, I listen to music for the first time in a week, half-falling asleep and in no time, I’m in Athens.

Where is home?

Barrage of guilt

As soon as I get home, all I want to do is shower and sleep.

The next morning, while logging into work after waking up too early to refresh the news sites, tears that did not come out of me all week long in Israel finally fall down like rain onto my keyboard.

Relief. My dome of protection has melted. Guilt is worse since I am safe now. My sister is not. So many of the people I grew up and lived with and alongside, and helped me become who I am, are no longer.

It’s so quiet here that you can hear a car passing two blocks away. I am under a heavy barrage of guilt.

I think of Sderot and of my parents, glad they are gone and unable to see this. To live through this. I think of being an orphan, I think about surviving and living on to tell the tale. I think of revenge and the bitter, fruitless tree it is.

Faces haunt my thoughts. I can’t sleep until very early in the morning, when it’s more like passing out. Now none of us can sleep, it seems.

I need to know

How am I still alive when others who deserved to live much longer, others so much younger, are physically no longer? Because I was in a different Zip code that morning?

An hour and a half drive, max, from the monsters, with the light traffic of 6:29am. As much as my mind, heart and body disagree at this moment — I know for a fact, I was lucky.

While in Israel I mostly read headlines, and did not allow myself the full details. But this defense is gone now. I need to know I did not close my eyes. I need to know the truth, the stories. And I need to say it out loud.

I’m not sorry that I was there, I don’t regret having lived through it. Though I managed to land 15 hours before the gates of hell opened, after a year of not being there, I was reminded once again of the question: Where is home?

Is home where you run to? Is it who you run away from? Is it where people love you or where people wish to do you harm?

No more illusions

Just like when my parents passed, then again during Covid, time itself seems to have melted into one big unit of space unknown. “Days” and “months” and “years” mean nothing now, especially for a child withering away in the dark.

I keep thinking of Sderot with a creeping sense of dread. Of the desert silence, the absolute peace of Shabbat. For three years I lived there under the complete illusion that there was no real risk — despite the rockets, despite having a student killed on campus once — that we were safe there, minutes away from slaughter.

Why does the world continue to tilt so sharply towards apocalypse, like a supermarket cart whose wheels have gone berserk? Does it not know how dangerous all of this is?

It’s so quiet in Athens. As I finish writing this around 4am, I hear a cat walking on my neighbor’s balcony. No alarms and no surprises.

Since I came back, well-intended people who couldn’t possibly understand — and why should they? — ask “How are you?”

Well. Apart from the lack of sleep, horrible images in my mind, the unexpected bursts of crying, the incessant refreshing of news sites, the general inability to watch or listen or read or do anything other than sleep, which I can’t, the pop-up windows of panic and guilt filling my mind about my sister and friends, the flashbacks of every type of PTSD I’ve ever encountered, the self-isolation at home since arriving, the inability to even go out to get a Coke Zero, well.

Apart from a deep fear of the near future, and complete disbelief in the far future — I am totally fine. And thank you so much for asking.

Sderot / Shimon Adaf

(translated by Ben Suissa)

It took me twenty years to love

This hole-in-the-middle-of-nowhere.

Cotton tubers have spread a white blaze

And the wind was against each cypress,

Until I could finally see

Clearly

The simple homes under the roof of clouds

Until I heard

The wondrous hum of the street.

A last breath of asphalt waves

Intertwined

With the sound of evening meeting the ground,

As the voice of a woman forgotten, that betrayed her

Giving away a truth

She had tried to hide in her face.

Years of breaking down

Have taught children to caress rock with water,

Puddle paper boats in ridiculous hope.

The girls’ circusy past had flown up with a flip of a skirt

As the crowd cut through it with its gaze.

Only loveless places gain your absolute love.