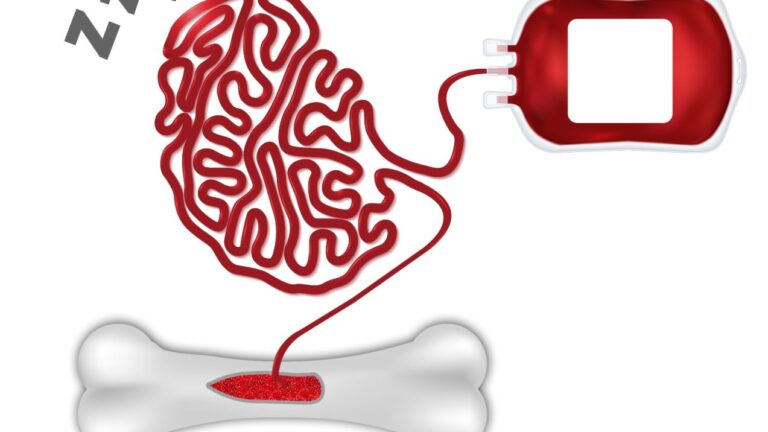

We all know that sleep deprivation can slow down reaction time, but now Israeli researchers have discovered it doesn’t just slow down our reactions, it also slows down individual neurons in our brain.

The neural lapse, or slowdown, affects the brain’s visual perception and memory associations, leading to delayed behavioral responses to events taking place around us.

“When a cat jumps into the path of our car at night, the very process of seeing the cat slows us down. We’re therefore slow to hit the brakes, even when we’re wide awake,” says lead researcher on the study, Dr. Yuval Nir, of Tel Aviv University’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Sagol School of Neuroscience.

“When we’re sleep-deprived, a local intrusion of sleep-like waves disrupts normal brain activity while we’re performing tasks,” he says.

The study, recently published in Nature Medicine, was an international collaboration led by Nir; Prof. Itzhak Fried of the University of California (UCLA), Los Angeles, TAU and Tel Aviv Medical Center; sleep experts Profs. Chiara Cirelli and Giulio Tononi, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Thomas Andrillon of the Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris; Amit Marmelshtein of Tel Aviv University; and Nanthia Suthana of UCLA.

Investigators recorded the brain activity of 12 epilepsy patients who had previously shown little or no response to drug interventions at UCLA. The patients were hospitalized for a week and implanted with electrodes to pinpoint the place in the brain where their seizures originated. During their hospitalization, their neuron activity was continuously recorded.

After being kept awake all night to accelerate their medical diagnosis, the patients were presented with images of famous people and places, which they were asked to identify as quickly as possible.

“Performing this task is difficult when we’re tired and especially after pulling an all-nighter,” says Nir. “The data gleaned from the experiment afforded us a unique glimpse into the inner workings of the human brain. It revealed that sleepiness slows down the responses of individual neurons, leading to behavioral lapses.”

In over 30 image experiments, the research team recorded the electrical activity of nearly 1,500 neurons, 150 of which clearly responded to the images. The scientists examined how the responses of individual neurons in the temporal lobe — the region associated with visual perception and memory — changed when sleep-deprived subjects were slow to respond to a task.

“During such behavioral lapses, the neurons gave way to neuronal lapses — slow, weak and sluggish responses,” says Fried. “These lapses were occurring when the patients were staring at the images before them, and while neurons in other regions of the brain were functioning as usual.”

Investigators then examined the dominant brain rhythms in the same circuits by studying the local electrical fields measured during lapses. “We found that neuronal lapses co-occurred with slow brain waves in the same regions,” Nir says. “As the pressure for sleep mounted, specific regions ‘caught some sleep’ locally. Most of the brain was up and running, but temporal lobe neurons happened to be in slumber, and lapses subsequently followed.

“Since drowsy driving can be as dangerous as drunk driving, we hope to one day translate these results into a practical way of measuring drowsiness in tired individuals before they pose a threat to anyone or anything,” Nir concludes.