When the Israel-Hamas war broke out, Lany Ilana Dekel Rosenberg was sure that the operation she leads to locate wounded wildlife and transport them to the hospital would grind to a halt.

After all, who had the time or mindset to worry about stranded animals with war raging around them?

But to her surprise, the rescue activity didn’t dramatically decrease.

“The numbers are almost similar to those of 2022, and a lot of it is thanks to civilians and to the army, which really emphasizes protecting wildlife. In the middle of fighting, soldiers care enough to pick up animals and to call our hotline,” Rosenberg tells ISRAEL21c.

“Even when all they want to do is eat or sleep, they still care. It’s amazing, and every time it moves me to tears to see how much they care about taking care of us and of our environment. It warms my heart and gives me so much strength.”

Rosenberg leads a project called Haibulance – the name is a mashup of the Hebrew words for “animals” and “ambulance” – that sees some 400 volunteers respond to calls of stranded wild animals.

They drive the creatures in their own cars to receive veterinary care at stations set up around the county or at the Israeli Wildlife Hospital at the Ramat Gan Safari.

The Haibulance project operates under the auspices of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, and arose when Rosenberg, who had already been working at the organization for years, was asked around seven years ago to help inspectors during the bird migration season.

“The help was appreciated, and we expanded our aid to the wildlife, focusing on extracting them and transporting them,” Rosenberg explains.

“Volunteers joined us along the way, and we opened WhatsApp groups based on geographic locations, eight groups in all. What started out as me and another few volunteers has grown to about 400 volunteers, and we also managed to establish cooperation with veterinary services in certain cities, zoos across Israel and different foundations. We’ve turned – and I say this fondly – into a monster.”

Rosenberg says she loves her job. “I have wonderful managers, and without their backing and care none of this could have happened.”

Better chances of survival

In the first year, Haibulance volunteers rescued some 1,500 animals. In 2021, the number rose to 9,000, and in both 2022 and 2023 there was an average of 7,000 calls from citizens reporting wounded animals.

“Their calls reach our hotline, and from there it moves to the geographic WhatsApp groups, where we ask who is free to volunteer. We have volunteers who go out on a call five times a year, and we have others who do it for 80 hours each month.”

Rosenberg stresses that the volunteers only transport small, non-dangerous mammals, birds and reptiles.

“We don’t allow the collection and driving of dangerous animals such as badgers or porcupines, or of … endangered species. Those type of animals need a special, straight-to-the-hospital ride, also in order not to pose danger to people,” she says.

“Our biggest challenge is to transport animals as quickly as possible under somewhat difficult conditions – after all, people are doing this on their own free time and at their expense,” Rosenberg notes.

Transit stations

For greater efficiency, the Haibulance project has established over 20 “transit stations” at the homes of volunteers who have received first-aid training and medical equipment.

“It really increases nicely the animals’ chance of survival,” Rosenberg tells ISRAEL21c.

“Let’s say you have a pelican from up north, they first reach a transit station where they get first aid that provides them with the boost they need. Sometimes all the animals need is simply water or food, or they’re exhausted from migration.”

But in some cases, the transit stations form the first station in a relay race all the way to the wildlife hospital in the center of the country.

Volunteers pick up and drive the animals a certain part of the way, before dropping them off with other volunteers who take them on the next stage of the journey.

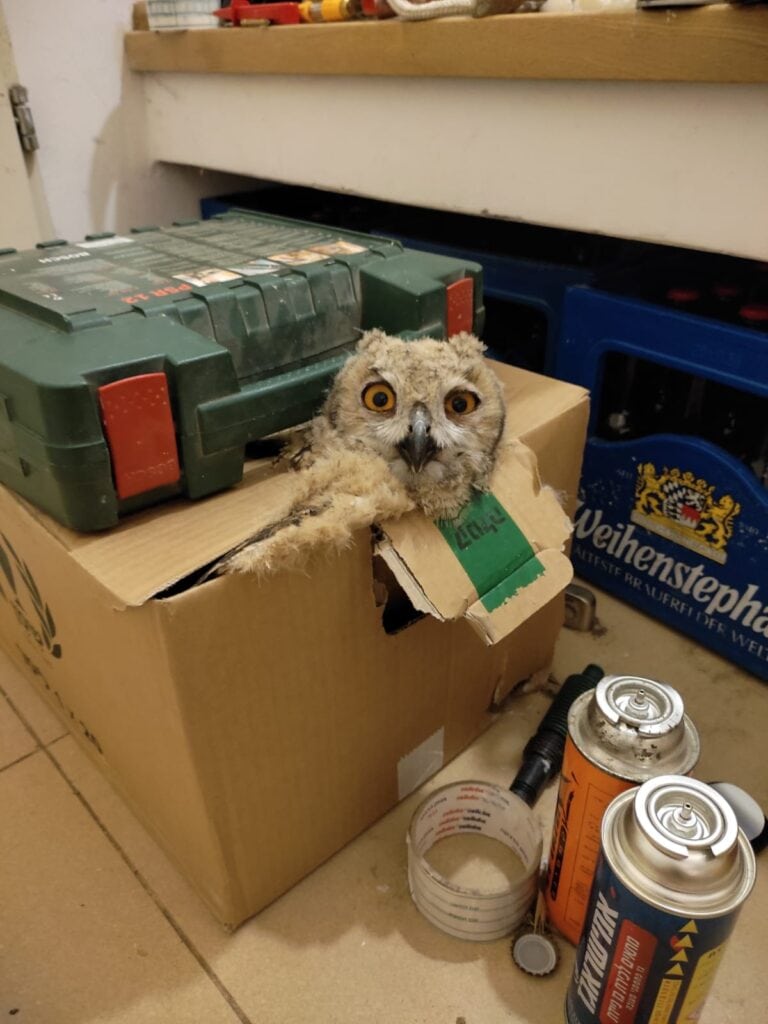

The animals travel in cardboard boxes that are easy to transport and to discard after housing sick animals.

The stork and the owl

Rosenberg’s very first case still stands out as the strangest one yet.

“I was sent up north to pick up a wounded stork. But I didn’t know how to approach her. The funny thing was that it attacked me and chased me – instead of her running away from me, I ended up running away from her,” she laughs.

Another strange experience, she says, involved rescuing an owl stuck between two lanes on Route 6 – Israel’s fastest highway.

“Our volunteers are not allowed to stop on the road, but I work for the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. In coordination with Route 6 workers, I stopped the Haibulance vehicle safely and stepped into this little traffic island and managed to catch the owl. I was so excited, because it was amazing that someone even noticed her, considering where she was stuck. She must have been hit by a passing car.”

Other animals are injured by explosions, fires, shooting or electrocution, not to mention war.

“The more we grow and develop, the bigger cities get, the more people, cars and buildings there are, and the more wildlife is hurt,” says Rosenberg.

“We as people are, reluctantly, harming nature, so the least we can do is return a favor.”

At the end of each year, when she contemplates having helped some 7,000 animals, Rosenberg says she feels “a very great satisfaction. There’s nothing better than feeling you’re doing something good and that you have a purpose.”

For more information, click here.