An Israeli billionaire businessman with a social conscience is building a technology park in an Israeli Arab city, hoping to develop the residents’ entrepreneurial spirit.

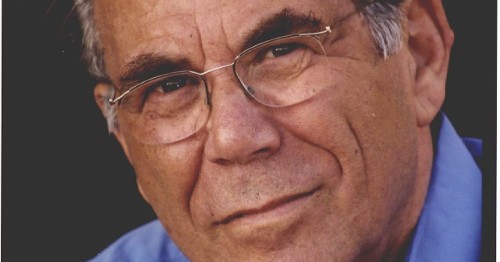

One of Israel’s richest men also happens to be one of the country’s most socially aware businessmen. Renowned for his modesty, industrialist Stef Wertheimer made billions in the metal industry and is now building his sixth technology park, this time in the Israeli Arab city of Nazareth.

Wertheimer has already built five tech parks, one in Turkey and four in Israel – including the model park Tefen that also provides opportunities for Israel’s Arab minority. But his vision for Nazareth is different; this time the park will be based inside an Israeli Arab population center.

Nazareth, a predominantly Muslim city with a significant population of Christian Arabs, was a natural choice for Wertheimer, especially because the area around Nazareth caters to a large population of both Arabs and Jews, he tells ISRAEL21c.

“My purpose is to keep people busy and out of mischief – to create good and interesting jobs for them that help families stay together. I want to get [the population around Nazareth] away from religion, and olive oil, and land and water – which have been the main issues – so they can be part of the free world,” Wertheimer relates.

In a way, the latest park may be a replacement for the one Wertheimer was hoping to build for the Palestinians before the second intifada broke out, shattering the deal. “I want the Arab and Jewish sectors both to be successful each in their own way,” he says.

Thinking globally, acting locally

Wertheimer’s original vision called for the building of a technology park in Gaza, to grow trade and industry for the Palestinians. “I was just days away from getting all the ‘okays’ from everybody and then the intifada made the whole thing impractical. I had signed letters and agreements in place.”

But focusing inside Israel proper is important for peace in the region, too, Wertheimer believes. And it may even help to curb terrorism. He dares to hope that the new technology park may go some way toward bridging the divide.

“There is mistrust on both sides,” he says, referring to allegations of land expropriation and water theft. He suggests that this lack of trust may be overcome not by coercion, but by allowing the two sides to be successful together.

Wertheimer thinks globally: “We must change the attitudes. Land and water are not the issues. We need to make this area a successful industrial area. The real problem will be how to get the word out in the market.”

Don’t ask him if he’s a social revolutionary. Wertheimer balks at the description. What he’s doing, he says, is just following a global trend: “The Irish made peace. Singapore is a successful place. South Korea is very successful after its independence. The Balkan area is relatively quiet now. All these places used tools that helped them to update modern industry.”

Equal entitlement to entrepreneurship

These countries, he continues, became successful because of their willingness to be part of the global market. That’s his vision for tech park number six in Nazareth. “We copied everything from other countries,” he says, referring to Tefen in the Galilee where, “The fact is that we created 10 to 20,000 jobs for Arabs and Jews and Druze, which has made the Galilee a very positive place.”

Eighty percent of Wertheimer’s family business Iscar was sold to American investor Warren Buffet in 2006 for $4 billion. But well before that his reputation and panache for social entrepreneurial projects was already in gear.

The success of his technology park Tefen, built in 1982, is “a result of not being successful in the Knesset (the Israeli parliament),” says Wertheimer. In the late 70s and early 80s he tried and failed to convince the government that it should differentiate between paid jobs and skills in the Arab labor force: “I wanted to educate the people,” he says, stressing that the Arab community has the same entitlement to entrepreneurship as its Jewish counterpart.

That failure pushed him to take matters into his own hands with Tefen, and he’s been going full steam ahead ever since. While the new technology park’s official status is that of a for-profit endeavour, Wertheimer says that despite its location on a site just over three acres in area it won’t be a real estate investment. “We’ll probably lose money,” he says ruefully.

However, in this case, that’s not the point. The park will include space for a combination of established and emerging industries and will also offer technical education in line with the European “Berufsschule” model (an economic model that encourages close relationships between the financial and industrial sectors to cultivate economic prosperity). If his track record in the Galilee is anything to go by, Stef Wertheimer will go some way toward transforming Nazareth into “a very positive place” as well.