Israeli typography designer Liron Lavi Turkenich has created a revolutionary writing system that merges Hebrew and Arabic letters in such a way that readers of either language can read the mashed-up words.

She calls her typographical system Aravrit, itself a mashup of the words for Arabic (Aravit) and Hebrew (Ivrit).

“I believe Aravrit sends a message that we’re both here, and we might as well acknowledge each other,” Turkenich told JTA. “We can do something caring for the other side just by reading, without having a solution.”

Lavi Turkenich, 32, is a lifelong resident of Haifa, Israel’s third-largest city, which has a mixed population of Jews and Arabs. Many signs in Haifa are printed in both Hebrew and Arabic, and most residents can only read their own language.

During her student days at Shenkar College of Engineering and Design in Ramat Gan, Lavi Turkenich thought it would be cool to find a way for the two related languages to “live together.”

She hit on a solution by studying the work of French ophthalmologist Louis Émile Javal. In the late 19th century, Javal discovered that people can decipher words in the Latin alphabet by seeing only the top half of the letters.

Lavi Turkenich did her own research and found that Arabic-readers also can read words by looking only at the top half of letters, while Hebrew-readers can understand a word by looking only at the bottom half.

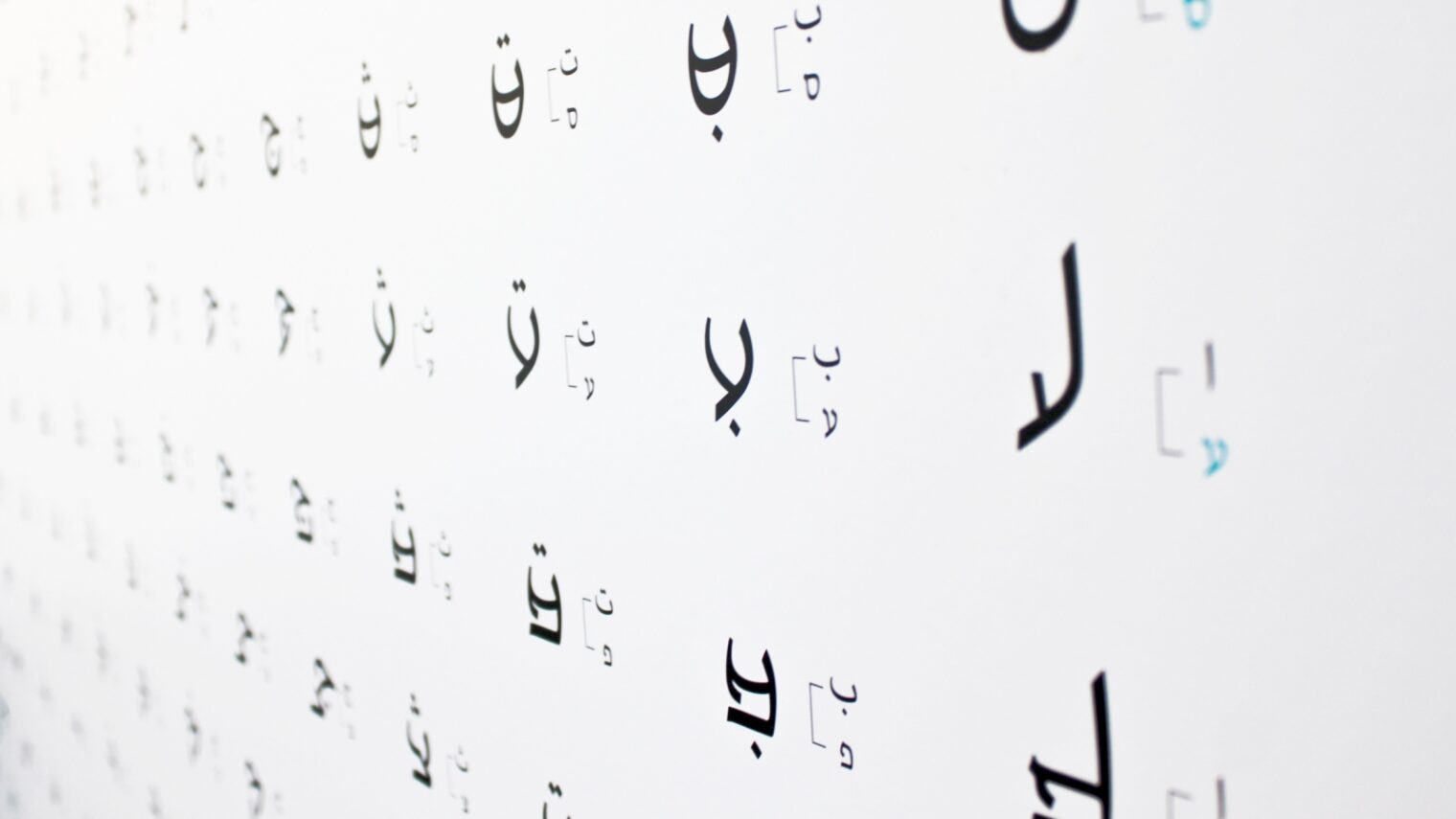

With input and advice from both Jews and Arabs, Lavi Turkenich eventually combined the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet with the 29 letters of the Arabic alphabet to come up with 638 characters in Aravrit.

“Aravrit is a project of a utopian nature,” Lavi Turkenich writes. “It presents a set of hybrid letters merging Hebrew and Arabic.”

She did her best to retain the characteristic features of each letter. “However, in both languages the fusion required some compromises to be made, yet maintaining readability and with limited detriment to the original script. In Aravrit, one can read the language he/she chooses, without ignoring the other one, which is always present.”

Lavi Turkenich gives lectures about her work around the world and is exhibiting Aravrit at the Museum of Islamic and Near Eastern Cultures in Beersheva, through the end of August.

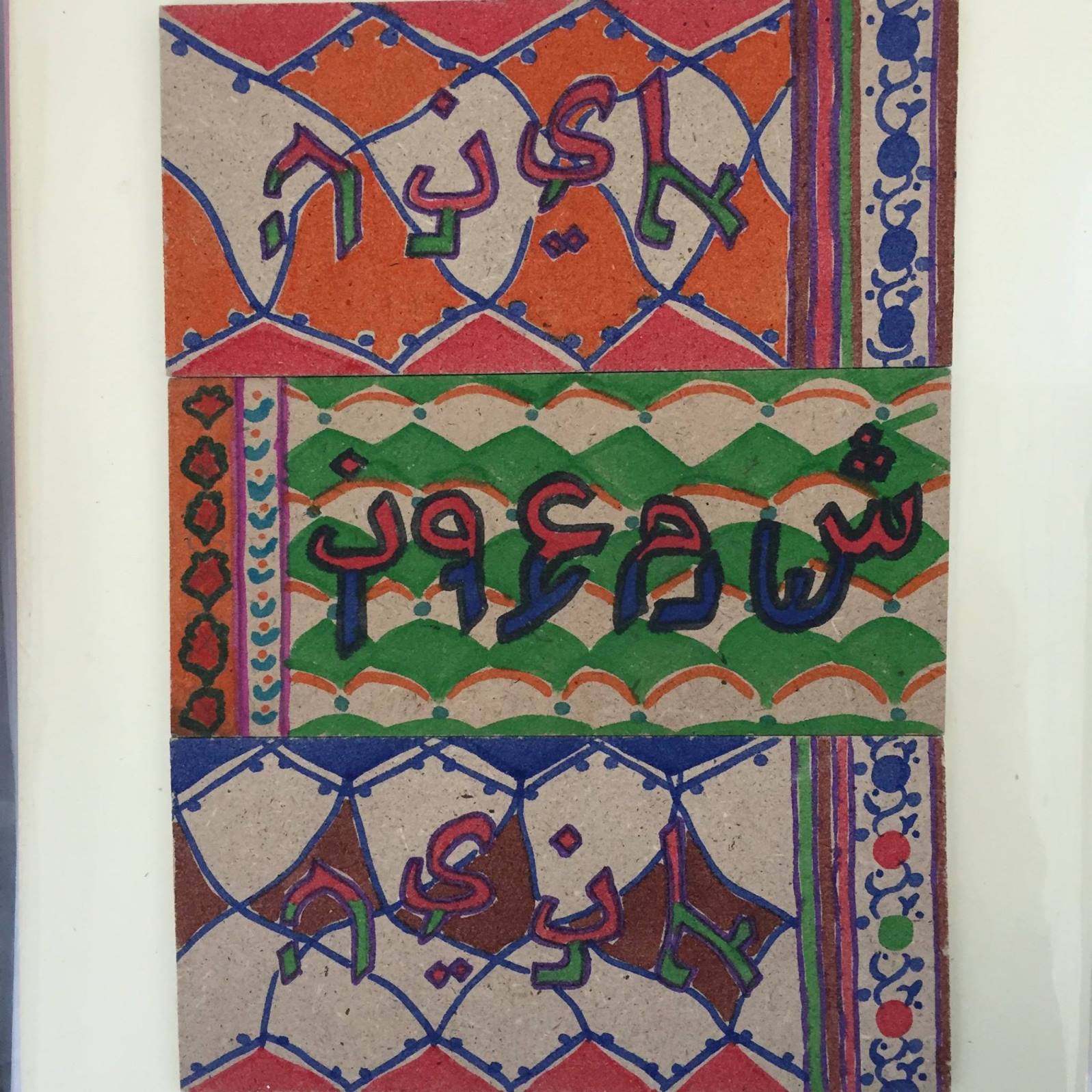

At the museum, she led a workshop showing children how to use Aravrit letters to make a name sign for their room. She hopes that one day Aravrit will be used for public signs as well.