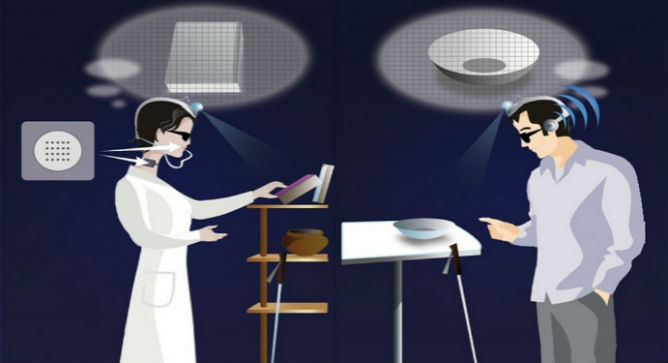

People born blind can be trained to visualize objects using sensory substitution devices (SSDs) programmed by scientists at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences and the Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada.

SSDs are non-invasive devices that provide visual information to the blind through their existing senses. For example, a visual-to-auditory SSD converts images from a miniature video camera into “soundscapes” that activate the visual cortex of the blind person, who listens through stereo headphones hooked up to a laptop or smartphone.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

Individuals trained in the laboratory of Dr. Amir Amedi can use SSDs to identify complex everyday objects, locate people and read letters and words.

After the SSD training period, researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study the organization of the visual cortex in the brains of the test subjects. The results were published several months ago in the journal Cerebral Cortex.

Seeing without eyesight

Previous studies already revealed that visual processing happens in two parallel pathways of the brain. The ventral stream, or the “what” pathway, apparently takes care of processing form, object identity and color. The dorsal stream is considered the “where/how” pathway, allowing a person to analyze visual and spatial information.

Amedi’s PhD student Ella Striem-Amit wanted to learn more about the role of visual experience in shaping this functional architecture of the brain. She theorized that maybe eyesight isn’t necessary in order for the dual processing mechanism to kick in.

Various kinds of SSDs developed in Holland and programmed in Amedi’s lab allowed her to test her theory. One of the devices is a tiny virtual cane, a patented invention whose sensors help blind people estimate the distance between themselves and the object at which the cane is pointing. The virtual cane emits a focused beam towards surrounding objects, and transmits the information to the user via a gentle vibration. This allows users to identify obstacles of different heights and to create a spatial mental picture to help them navigate between the objects.

“The use of the device is intuitive and can be learned within a few minutes of use,” said Amedi.

Using fMRI following sensory substitution, the Hebrew University researchers discovered that the visual cortex’s two-pathway division of labor was indeed activated by sounds that convey the visual information. Striem-Amit was correct: The complex system isn’t dependent on eyesight.

The brain is a ‘task machine’

Amedi’s team and other research groups have suggested that many areas of the brain find ways to accomplish tasks regardless of the format of the information coming in.

“The brain is not a sensory machine, although it often looks like one,” said Amedi. “It is a task machine.”

This newest study further supports such a notion, and shows that the brain of a congenitally blind person could be trained to process visual information with the aid of visual rehabilitation devices – including, perhaps, an SSD hybrid prosthesis.

“The exciting view of our brain as highly flexible task-based and not sensory-based raises the chances for visual rehabilitation, long considered unachievable, given adequate training in teaching the brain how to see,” summarized Amedi’s students Lior Reich and Shachar Maidenbaum in Current Opinion in Neurology.

In the future, SSDs could not only help scientists assess the brain’s functional organization, but could also serve as aids for the blind in daily visual tasks. The devices could even be used to visually train the brain prior to eye surgery, and to augment vision after the surgery.