A young man walks into the Barsheshet & Ribak shofar factory in Tel Aviv a few weeks before Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year.

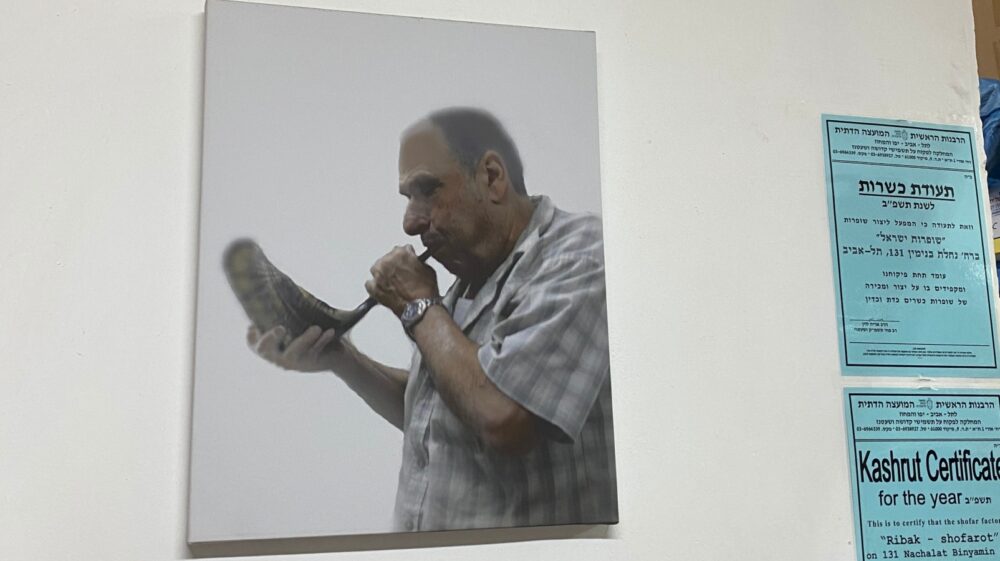

It’s nearly five o’clock and the workshop is shutting soon. But Eli Ribak is staying late anyway to talk to ISRAEL21c about his rare craft, and he welcomes the visitor and his wife, who schlepped by bus from a southern suburb of Jerusalem.

Before I could ask the customer why he didn’t simply buy a ram’s horn (shofar) at any Judaica or souvenir shop close to home, he answers that question.

“My father bought his shofar here 30 years ago, so I’ve come here too,” he tells Ribak.

The owner smiles. He hears this all the time.

Especially before Rosh Hashana, which the Bible calls “Yom Teruah,” the day the shofar is sounded.

Rosh Hashana is considered a day of divine judgment. In the synagogue, 100 blasts of this natural trumpet punctuate the long Rosh Hashana liturgy as a wakeup call to repentance and a fanfare for the King of Kings.

The designated shofar-blower needs a kosher horn, meaning it has no cracks or holes and no added materials such as glue or paint.

It must have the right shape and mouthpiece for the individual shofar-blower to be able to fulfill every congregant’s obligation to hear a specific series of sounds — the long tekiah, three short shevarim and nine staccato teruah blasts, finished off by an extra-long tekiah gedola.

And that’s why this young man is here today, seeking expert guidance in purchasing the right horn.

Ribak, 52, and Zvi Barsheshet, 67, are among very few craftsmen producing shofars in Israel. Their families have been turning animal horns into sacred musical instruments since the 14th century.

The 15-generation business has an extraordinary story.

A Polish-Moroccan partnership

Ribak’s great-uncle immigrated to what was then Palestine from Poland in 1927 and set up shop in Tel Aviv, later handing the business down to Ribak’s father.

Barsheshet’s father emigrated from Morocco via France in 1947 aboard the Exodus ship that was seized by the British and the passengers diverted to Cyprus. After his release from internment, he established a shofar workshop in Haifa.

“My father and my partner’s father were competitors. Thirty years ago, they decided to work together,” Ribak tells ISRAEL21c.

Ribak initially took a different career path: He has a master’s degree in materials engineering from the Technion and worked at Motorola for 17 years.

“Nine years ago, when my father died, I quit high-tech and joined Zvi,” he says.

He shakes his head with a wry smile. “I don’t believe a normal person would go into this business. It’s very hard work.”

No two identical shofars

Ribak observes how his customer holds the horn and which part of his mouth he blows from as he begins testing a variety of ram’s horns piled in cardboard boxes.

“You have to adapt the shofar to the person,” Ribak explains.

“And each shofar is individual. Every day, I get customers who want the same shofar their father had, or the same shofar they had when they were younger. But there are no two identical shofars just as there are no two identical people.”

Sheep, goat, antelope

The tradition of using a ram’s horn as a sound machine dates from biblical days.

Perhaps the most famous shofar story is in the book of Joshua, when the Israelite priests circled Jericho while blowing their horns, and the city’s walls came tumbling down.

Today, shofars can be heard at special occasions such as weddings. Many Jews sound the shofar every morning (except Shabbat) during the month preceding Rosh Hashana and at the end of the Yom Kippur fast.

And people of all faiths collect natural and decorative shofars as souvenirs. Often made in Morocco, China or India, they are easily available in Israel and abroad.

Although Barsheshet & Ribak’s factories also make shofars embellished with painted designs or precious metal coatings, only the unadorned natural ones get a sticker certifying that they’re kosher for Rosh Hashana use.

“Hearing the shofar is the only mitzvah associated with the Jewish New Year,” says Ribak. “The responsibility for the whole congregation rests on the validity of the shofar that is used.”

The animal from which the horn comes — typically a ram (adult male sheep) and sometimes a goat, oryx, kudu, gazelle or other antelope – has to be a kosher variety but does not have to be slaughtered according to kosher food regulations.

In fact, Ribak informed me, “We import the ram horns from suppliers in Arab countries.” That’s because mutton is a staple of the Muslim diet (“In Israel, we eat mainly chicken,” Ribak says).

How do the horns arrive from countries that don’t have diplomatic relations with Israel?

“We bring them in through a third country,” Ribak says. “It’s never a problem.”

Stages in the making of a shofar

Every horn in each shipment is inspected at the factory for cracks or holes. Only about 30 percent meet the conditions to be kosher shofars, according to Barsheshet.

Trained workers begin the manufacturing process by extracting the bone inside the horn to create a hollow interior.

Ribak explains that the word shofar (pronounced “show-FAR”) signifies a hollow object. It has a deeper meaning as well. The verb form from which it derives, l’shaper, is Hebrew for “to improve.”

“When you blow [or hear] the shofar on Judgment Day you are expressing that you want to be a better person in the new year,” he says.

After the horn is hollowed, a mouthpiece must be created in the sealed narrow end. This requires trimming and drilling.

Different traditions, different tones

There are many styles of shofar, reflecting the differing traditions that developed among Jews in the far-flung diaspora over 2,000 years: Ashkenazic, Yemenite, Moroccan, Babylonian, Italian and others.

Some traditions forbid altering the horn’s natural shape or texture. Other traditions allow the horn to be polished and the mouthpiece area to be heated so that the curve can be straightened for easier drilling.

“If you heat it too much or straighten it too strongly, it will crack,” says Ribak, showing us an overheated horn that looks like a toasted marshmallow. “The more you practice the less you damage the horns.”

Sanding and polishing a ram’s horn thins it somewhat, resulting in a higher pitch. How an individual shofar sounds also depends on the degree of its curve and the strength of the air being blown into it.

Rybak says that as people age, their lung power can diminish so that the same shofar sounds a bit different.

Plain and fancy

Barsheshet & Ribak’s Tel Aviv and Haifa locations produce approximately 1,000 shofars per month, on average. They’re sold to Judaica shops and wholesalers in just about every country except China.

“We start sending out our Rosh Hashana inventory right after Passover because we ship by sea and it takes time,” says Ribak.

A small shofar retails for about 60 shekels ($18), while a large, custom-made shofar can cost 2,000 shekels ($615). Most customers spend in the range of 500 to 900 shekels, says Ribak.

Jews of Yemenite descent usually use an unpolished ram’s horn for Rosh Hashana. But it’s the long, spiral Yemenite antelope-horn shofars that many customers crave as a showpiece or collector’s item, and these fetch the higher prices.

The longest antelope horn currently in the Tel Aviv shop measures 57 inches.

“People order custom designs painted on them,” Ribak says, showing us a kudu shofar embellished with pictures of Israeli and American flags, and another with a lion motif. “We have tons of different designs.”

The shofar that Ribak blows on Rosh Hashana for the congregation he belongs to in Shoham is Moroccan style, a polished ram’s horn with delicate carvings.

Is it difficult to learn how to coax sounds from a shofar?

“It is a technique,” Ribak replies, “and once have the technique it’s very easy to blow. Of course, you need a good shofar.”

For more information, click here