Millions of Christian pilgrims visit Israel every year to walk in the footsteps of Jesus. They follow tour guides on Jerusalem’s Via Dolorosa, hike the Abraham and Jesus trails in the Galilee, and visit Nazareth, where Jesus gave sermons to his followers.

Now there may be a brand-new pilgrimage stop to witness where one of the biggest New Testament miracles took place: where Jesus walked on water.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

To date, the exact location of this miracle out at “sea” is not known.

Israel’s newest archeological discovery, practically a stone’s throw from the baptismal site of Jesus on the River Jordan, may provide a clue, though nobody really knows yet what it is.

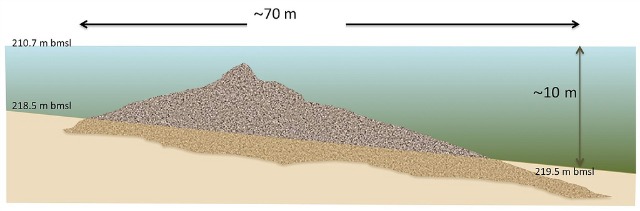

Israeli researchers led by Prof. Shmulik Marco from Tel Aviv University, who recently reported this discovery in the Journal of Nautical Archaeology, uncovered a third-century BCE mound of stones out in the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret to Israelis).

Come summer, the top of the mound almost pokes out of the water, lending enough space for birds to rest several hundreds of meters out in Israel’s only freshwater lake.

While the mound of stones, conical in shape, and about 70 meters from side to side certainly pre-dates Jesus, Marco tells ISRAEL21c, one of the theories is that the stones may have provided the platform for one of Jesus’ miracles out in a stormy sea where he walked on water and was able to rescue followers.

This platform would have provided a small pedestal upon which Jesus could have stood, Marco points out.

This theory, and others about how the stones got there and why, are some of the unanswered mysteries that led Marco to publish the research this year on the submerged stones. The stones were originally unearthed by his underwater team using imaging technology to survey the southwestern tip of the Sea of Galilee for evidence of tectonic shift and ancient earthquakes –– his specialty.

Marco says that remains of 20,000-year-old fishing huts near the mound indicate that the lake was an important source of income and food for earlier people in the region, while the mounds themselves probably correspond to an ancient city nearby, called Beit Yerah.

After intense prodding from the archeological community about the potential significance of these stones ––likely a cairn to protect ancient remains, Marco postulates –– he and his team went ahead with publishing the news.

Messing with the bottom of the lake

“Upon discovering the mound, we immediately realized that it was manmade,” says Marco. “But honestly, we didn’t think that we’d come across something that was that important. Going into the Sea of Galilee, we were mainly interested in the composition of the bottom of the lake, so we didn’t focus on the archeological aspect. Out of our focus range, we decided to ‘give in’ to the archeologists after significant prodding from their side.

“So we went ahead, and said let’s publish this news even if we don’t understand its meaning or importance.”

This news has sparked many exciting international debates in the archeological, scientific and theological communities around the world, says Marco.

Now he and his team, and other specialists in the field, are seeking research funds to continue exploring this underwater mystery, but there will be hurdles ahead.

They face immense bureaucratic challenges, as local authorities are extremely protective over the Sea of Galilee and its bounty of hidden archeology remains.

“The administration there is very touchy about anyone messing with the bottom of the lake,” says Marco.

And for good reason: The Sea of Galilee and what lies there unearthed is not only significant for the Christians. The surrounding city of Tiberias was a religious center for Jewish scholars in the Second Temple period.

But there are technical problems, too.

“The water is very murky,” says Marco. When diving, I could only see about one-and-a-half to two meters in front of me, making it hard to excavate such a large structure.”

Marco says that the stones of the ancient cairn are wedged together tightly with sediment, so it’s not likely that they could send a probe down into the stones — which probably were assembled on land and shifted into the lake after a powerful earthquake, he surmises. He could prove this theory if he could take samples of the sediment below the stones, from the edges of the mound.

If Marco were able to date sediment from land, and connect it to a past earthquake or abrupt tectonic shift after the time of Jesus, he would be able to say with confidence that Jesus did not walk on water at that site.

And if the stones were already out in the water at the time of Jesus? Then this question will remain open and yet another Holy Land mystery will be ready for debate.