Dr. Hagai Levine worries about four-year-old Abigail Edan, who saw her parents murdered by Hamas terrorists before she was kidnapped to Gaza on October 7 and released on November 26.

He worries about 84-year-old Alma Avraham, deprived of essential medication for the seven weeks she was captive in Gaza.

He worries about each of the remaining approximately 160 hostages, from the youngest baby to the oldest octogenarian.

But Levine isn’t just sitting around fretting.

While national leaders are working out the difficult details of getting hostages released back to Israel, Levine is working out the difficult details of their medical care.

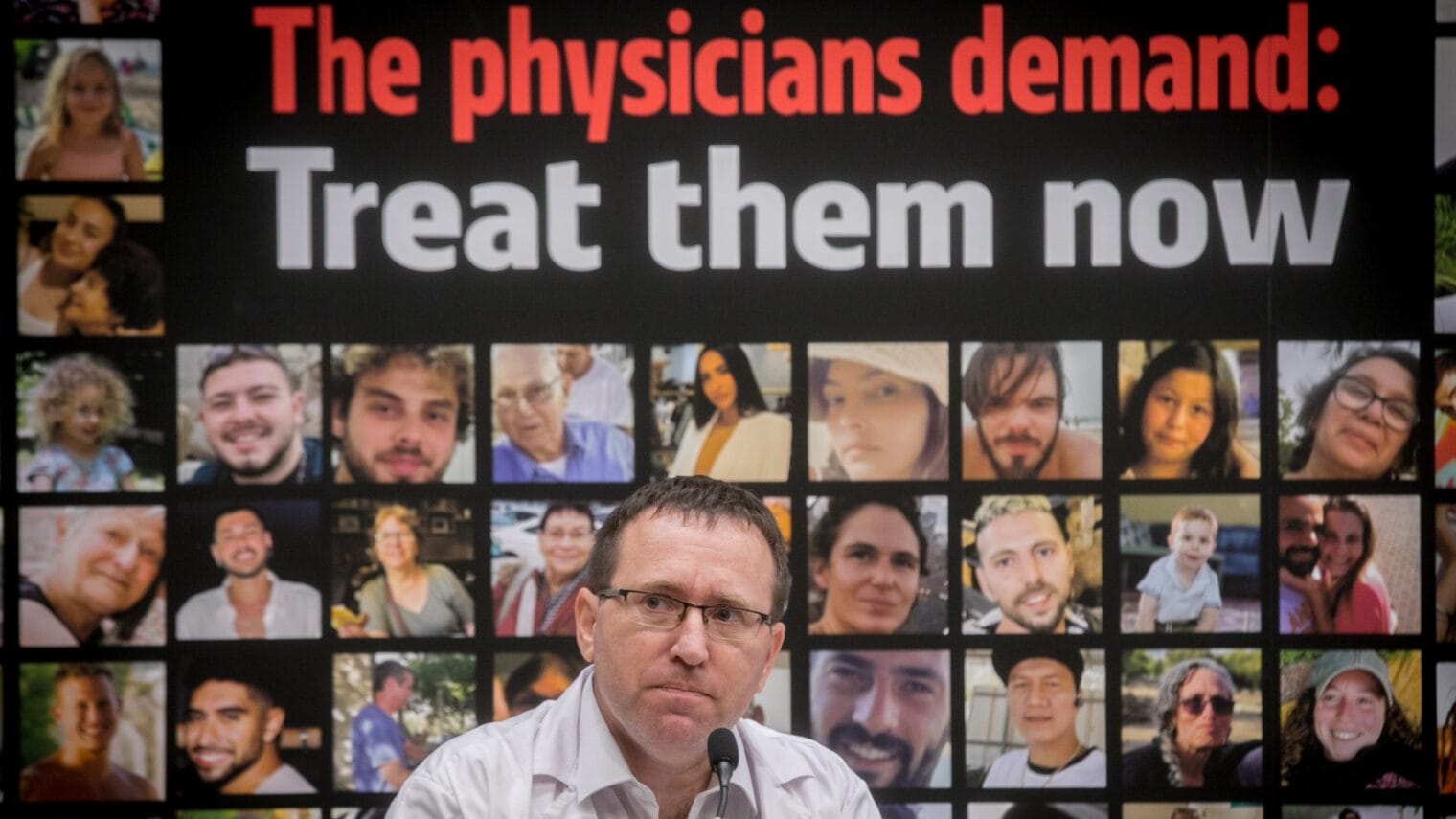

Levine, chairman of the Israeli Association of Public Health Physicians, volunteered to head the medical team of the Hostages and Missing Families Forum established by the families of the approximately 240 abductees less than 24 hours after the deadly Hamas attacks and kidnappings of October 7.

“This is an unprecedented event,” says Levine.

“Hostages ranging from a nine-month-old baby to an 85-year-old woman with dementia and Parkinson’s were taken and held underground in inhumane conditions. Hamas did not allow them access to the Red Cross or connection with their families,” he says.

“Very early on, we established a medical and resilience team with the aim of bringing them home now, safely, and protecting the health of the hostages and their families.”

Levine and the forum worked with the Health Ministry to innovate new guidelines for treating released hostages.

“We are writing a textbook that wasn’t written before because nothing like this has ever happened before,” adds Orna Dotan, head of the forum’s resilience team comprising hundreds of mental-health professionals.

The doctor of 70 hostages

Levine was a leading figure in medical policymaking during the pandemic.

Over the past year of massive protests against the government’s proposed judicial overhaul, he led the White Coats – Healthcare Professionals for Democracy protest group.

When the October 7 Hamas rampage turned the entire nation’s attention to the trauma of the dead, wounded, kidnapped and missing, Levine jumped in to guide Israel through yet another public-health crisis.

“We combed the literature about how to treat released hostages. I met with the Red Cross, the World Health Organization and many diplomats around the world. I spoke with two hostages released earlier to see how we can best prepare to treat the next ones,” Levine says.

He also gathered personal medical information on the hostages. Among those he consulted was Dr. Sharon Kleitman, a family physician in the Negev who counts 70 of the captives among his patients.

“All the hostages need medical care,” Levine emphasized to reporters in a presentation organized by MediaCentral.

“At least a third of them have chronic conditions for which they need medication. Some hostages are severely wounded, with amputated limbs. We don’t know if and how they were treated.”

He noted that Yagel Jacob, 12, has a peanut allergy. In a photo released 34 days into captivity, Yagel “looks pale and lost weight –maybe he’s afraid to eat,” Levine speculates. (Editor’s note: Yagel was released on November 27.)

“We need to hope for the best and prepare for the worst,” is the philosophy guiding his task.

To feel human again

The forum works with the Ministry of Health and with the hospitals designated to receive released hostages to make sure they get sensitive and proper treatment immediately and throughout the long recovery period.

“It’s very challenging. Our recommendation is to be professional, personal and patient,” says Levine, who advocates a multidisciplinary, holistic, step-by-step approach.

“After all they have been through, including the many-stage experience of returning home, first of all the hospitals must provide a protected and calm environment where they can recover,” he says.

Providing that kind of environment begins with how best to examine the released hostages to make them feel safe.

Should children be examined only with a parent in the room? Should released family groups be examined together or separately? Should female hostages, who may have been sexually assaulted, be examined only by female healthcare professionals?

“The hostages were used by Hamas as objects and now they need to feel human again,” says Levine.

“For some, the most important immediate need is hugging their mother. The bigger issue is for them to gain back control over their lives, and this is a process,” he explains.

Needs of hostages and families

“We have to prioritize their needs, such as dental care, eyeglasses, hearing aids, even proper shoes because many were abducted barefoot,” says Levine.

“They may have vitamin deficiencies — especially the children and the elderly — and we know that we need to address nutrition slowly, step by step.”

The families, too, will receive tailormade treatment, says Dotan.

“The families are in the most challenging circumstances in their lives. They waited for many weeks without knowing if their loved ones are dead or alive. Now they have to wait longer to see how they are after their release.”

For the loved ones of hostages still in Gaza, including families where the mother and children have been released but not the father, the emotional turmoil is unimaginable, Dotan says.

With every hostage and family member treated, the forum plans an ongoing assessment to learn lessons from each one and do better for the next ones, pledges Levine.

“It is a process of taking them from darkness to light.”