A significant link between behavioral stress and the effectiveness of vaccines was demonstrated for the first time, in a study published in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity by researchers at Tel Aviv University.

They found that acute stress in mice nine to 12 days after vaccination increases antibody response to the vaccine by 70 percent compared to a control group.

However, the diversity of antibodies in the stressed mice was reduced, resulting in diminished protection against the pathogen’s variants.

“The prevailing assumption is that the effectiveness of a vaccine is determined mainly by its own quality. However, over the years, professional literature has reported influences of other factors as well, such as the age, genetics, and microbiome of the outcomes of vaccination,” said clinical microbiologist and immunologist Natalia Freund, in whose lab the study was done by PhD student Noam Ben-Shalom.

“Our study was the first to investigate the possible effects of acute stress. We found that this mental state has a dramatic impact – not only on the vaccine’s effectiveness, but also on how it works,” said Freund.

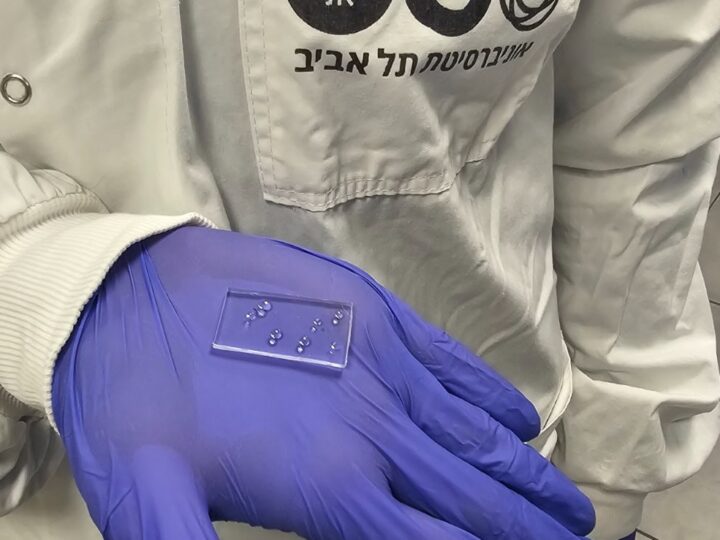

The team gave mice two different vaccines: the model protein Ovalbumin and a fragment of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein also used in the Covid-19 vaccine. Nine days later, just as the adaptive immunity became active and the production of antibodies began, the mice were subjected to a widely used behavioral paradigm simulating acute stress.

“Initially, we were surprised to find out that the response to the vaccine was much more effective in animals that had experienced stress,” Freund said.

“We would have assumed just the opposite – that stressful situations would have a negative impact on the immune system. Nevertheless, with both types of vaccines, we observed a stronger immune response after stress, both in the blood and in B cells [the lymphocytes that produce antibodies] derived from the spleen and lymph nodes of the immunized mice.”

At the same time, she said, “to our great surprise, the breadth of the immune response generated by the vaccine was reduced by about 50% following stress. In general, the purpose of vaccination is not only protection against a specific pathogen, but also creating a long-lasting immunological memory for protection against future mutations of that pathogen. In this sense, the vaccines appeared to lose much of their effectiveness after exposure to stress.”

The researchers then studied whether humans also display the post-stress immune impairment observed in vaccinated mice. For this purpose, they cultured B cells obtained from blood of people who had contracted Covid-19 in the first wave, and induced stress in these cultures using an adrenaline-like substance.

“We discovered that just like in mice, human cells also exhibit a zero-sum game between the intensity and breadth of the immune response,” said Freund.

“When the adrenaline receptor is activated during stress, the entire immune system is stimulated, generating antibodies that are 100-fold stronger than antibodies produced in cells that had not undergone stress. But here too, the response was narrower: the diversity of antibodies was reduced by 20-100%, depending on the individual from whom the cells were taken.”

She explained that physical illness causes a form of stress.

“When the body contracts a virus or bacteria it experiences stress, and signals to the immune system that the top priority is getting rid of the pathogen, while investing energy in long-term immunological memory is a second priority,” Freund said.

“Therefore, stress nine to 12 days after vaccination, at the time when B cells are generating high affinity antibodies, enhances short-term immunity and damages long-term memory.”

The other PhD student involved in the study was Elad Sandbank from the neuro-immunology lab of Prof. Shamgar Ben-Eliyahu.