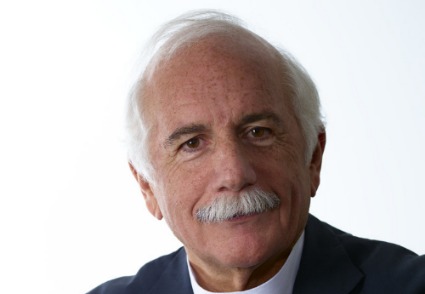

Israel-born Moshe Safdie is firmly rooted in the soil from which his ‘humane designs’ rise above the landscapes of the US and Asia.

The architect of some of Israel’s most iconic structures, from Yad Vashem to the Mamilla and David’s Village compound that links the Old City with modern Jerusalem, has created housing, hotels and museums – even a mosque – that dot the globe.

Yet to his surprise, Moshe Safdie is usually described as a Jewish or Israeli architect. “For better or worse, it’s part of my identity,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

It’s not that these adjectives aren’t accurate. Safdie was born in Haifa in 1938 to a Jewish family with roots in mystical Safed (hence the surname) and later in Aleppo, Syria. He maintains a branch office in Jerusalem and votes in every Israeli election. The modifiers are, however, a bit limiting for a world-renowned urban planner, theorist, educator and author who is a proud citizen of three countries.

Growing buildings instead of crops

Safdie was 15 when his parents decided to immigrate to Canada. After a carefree childhood raising bees and chickens and going on scouting expeditions with his friends in the gestating state of Israel, the change was traumatic.

“When we were 13 or 14, we all pretty much figured we’d go to Nachal [the Fighting Pioneer Youth infantry brigade] and then form our own kibbutz,” he says, recalling that he was an ardent Zionist and socialist even as a teen. “I was going to study at Kadouri Agricultural School, where Yitzhak Rabin had studied. Now, I had two years of high school left, and agriculture had vanished as an option.”

An aptitude test revealed the young man’s strengths in math and art, pointing toward a career that would combine both. “Had I not left Israel,” he reflects now, “I might not have been an architect.”

Safdie studied for six years at Montreal’s McGill University. His groundbreaking thesis on experimental prefabricated housing formed the basis for his first major project — the master plan for the 1967 Montreal International and Universal Exposition.

Habitats in Montreal and Modi’in

“I proposed a habitat — a sort of a fairy tale — and it got approved and built. That was the beginning of my professional practice,” he says. Many years later, he would put some of the same “humane design” principles into play when designing Modi’in, one of Israel’s first planned cities.

However, every Safdie creation is uniquely specific to place and culture. “A building cannot be experienced as independent of the land in which it is rooted,” Safdie says.

Before pulling out his sketchpad to begin a new project, he spends considerable time at the site and with the client, absorbing the subtle messages of physical context, culture, past and symbolism.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes Remembrance Authority museum complex that Safdie had a hand in creating from 1987 to 2005, was one of his most challenging assignments “from the point of view of coming up with architecture that can resonate with the charge of memory and history.”

An avid student of biology and physics, he endeavors to harmonize his structures with their natural setting. “I am interested in how nature evolves designs to respond to the survival of an organism and in applying these principles and sensibilities to architecture,” he says.

Indigenous materials are key to this approach. For the new Ben-Gurion International Airport near Tel Aviv, completed in 2004, Safdie incorporated Jerusalem stone and rainwater elements “to show the significance of water in our culture and ecology.” Mindful that this building represents Israel to millions of visitors, he designed its central rotunda “as a gateway to the country where passengers arriving and departing pass each other in a celebratory way.”

Global citizen

Safdie says he maintains “a trilogy of loyalties” to Israel, Canada and the United States.

Safdie and his wife, Jerusalem-born photographer Michal Ronnen Safdie, moved to Massachusetts shortly after he became director of the urban design program at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design in 1978, a position he held for 12 years until his practice left him little time for academia. Safdie Architects is based near Boston and has offices in Toronto and Singapore as well as Jerusalem.

He returned for the first time to his native country after the 1967 Six-Day War, with an assignment to mastermind restoration projects in and near the ancient quarter of the capital city.

This commission turned into the most monumental, and often frustrating, accomplishment of Safdie’s 40-year career. Due to myriad logistical and bureaucratic hurdles, 35 years went by from the time he began renovating the first structure, Yeshiva Porat Yosef opposite the Western Wall, until completion of the blockbuster final piece, the Mamilla residential and shopping complex and luxury hotel.

Several other plans were conceptualized but never built, including housing in the Jerusalem Forest, which was scrapped in the face of overwhelming public disapproval. Political problems have plagued Safdie’s vision for the renovation of the City of David, which he formulated partially with the aim of regularizing and legalizing the status of the neighborhood’s many Arab squatters.

Safdie, who speaks Arabic, says he maintains close relationships with Palestinians and often receives inquiries from students and faculty in Muslim countries. He has designed projects in Senegal and Iran, a mosque in Dubai and the Asian University of Women in Bangladesh, where he was feted by the prime minister and foreign minister.

“Global Citizen: The Architecture of Moshe Safdie” premiered at the Safdie-designed National Gallery of Canada in October 2010 and will travel around North America over the next two years.

The exhibit’s curator, Donald Albrecht of the Museum of the City of New York, said Safdie is “especially adept at realizing the aspirations of a surprisingly diverse group of clients.”

Urban to rural, small to mega

Safdie’s completed works run the gamut in terms of setting and scale.

Among his many well-known designs are the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Harvard Business School master plan, the Ford Center for the Performing Arts and Vancouver Library Square in British Columbia; Exploration Place Science Center in Wichita, Kansas; the Salt Lake City Main Public Library, Utah; the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts; the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia; and Pearson International Airport in Toronto.

Now 73, Safdie has five new projects opening this year: Marina Bay Sands Resort in Singapore; the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts in Kansas City, Missouri; the United States Institute of Peace Headquarters, Washington, D.C.; the Khalsa Heritage Center in Punjab, India; and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Also under construction are an addition to Safdie’s Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles; the National Campus for the Archaeology of Israel, in Jerusalem; and a high-density residential development in Qinhuangdao, China.

The would-be farmer has certainly cultivated the land, even if not in the way he had expected.