Researchers in Israel are warning that stem cell treatments could raise cancer risks.

Using a patient’s own stem cells to replace diseased or damaged tissues might expose the patient to the risk of cancer, according to the results of new research at the Hebrew University (HU) of Jerusalem released this month.

The discovery raises a cautionary flag in the advancing field of stem-cell therapy. For years, embryonic stem cells were the focus of this field because they are undifferentiated and therefore have the potential to develop into any cell type in the adult body.

In 2007, Japanese scientists innovated a method for creating embryonic-like stem cells from mature human cells. The idea of obtaining a patient’s own cells for treatment became an attractive alternative to the controversial harvesting of cells from human embryos.

Chromosomal changes readily identified

The problem is that stem cells must be raised in lab cultures for an extended period before being used for therapy. Research carried out under Nissim Benvenisty, the Herbert Cohn Professor of Cancer Research at the Silberman Institute of Life Sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has now shown that during this period the adult stem cells (also called induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells) undergo chromosomal changes. Some of these changes characterize cancerous tumor growth.

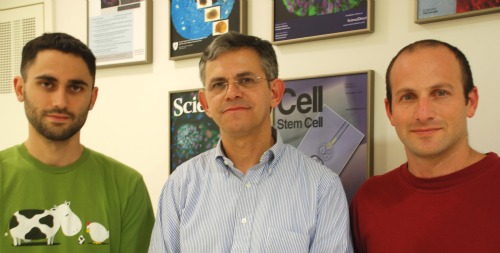

Benvenisty, together with his post-doctoral fellow Yoav Mayshar and his doctoral student Uri Ben-David, developed a new analytical method for determining the genetic structure of the chromosomes of 100 cell lines from 18 different laboratories around the world, in addition to some from their own lab.

They discovered that, over time, some iPS cells develop an extraneous copy of a particular chromosome and begin to overpower the normal cells in the culture. This phenomenon is known to underlie abnormal tissue development, including cancerous growths.

Danger may hinder pace of research

In an article published in the October issue of Cell Stem Cell, the journal of the International Society for Stem Cell Research, the Hebrew University researchers noted that the chromosomal changes appeared systematically in genes on chromosome 12.

This discovery is likely to hinder progress in developing human iPS cells in future therapy.

“Our findings show that human iPS cells are not stable in culture, as was previously thought, and require reassessment of the chromosomal structure of these cells,” said Benvenisty, who recommended taking “great care in continuing to work with them.”

The discovery has been patented by Yissum, Hebrew University’s technology transfer company, which is currently searching for commercial partners for further research and development.