Are sexual function and satisfaction affected by exposure to disturbing wartime images?

Does the stress of living through a war cause changes in sexual behavior? And do those changes vary by gender?

Three weeks into Israel’s war with Hamas, Israeli experts embarked on an unusual study to find out. They believe this data is crucial for developing comprehensive mental-health interventions for people in conflict zones.

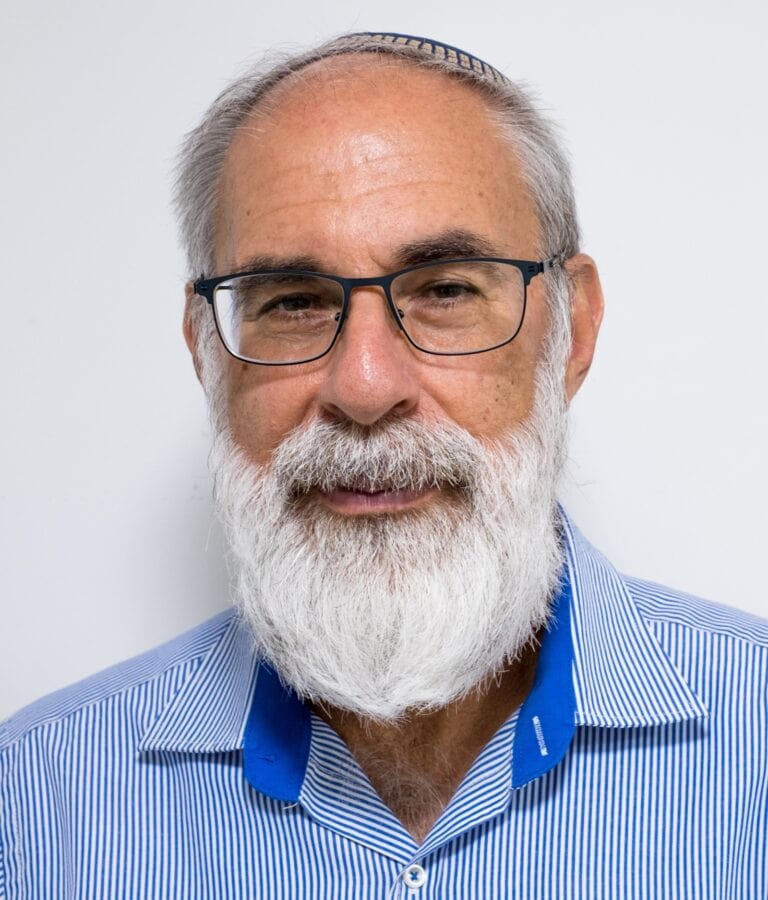

“I initiated this study to understand how war affects intimacy,” says industrial and organizational psychologist Aryeh Lazar, an associate professor at Ariel University, which funded the study. He is a researcher in the psychology of religion, spirituality and sexuality.

Lazar designed the survey with two experienced trauma and sex therapists: individual and couples therapist Talli Rosenbaum; and University of Haifa School of Social Work Associate Prof. Ateret Gewirtz-Meydan, head of the university’s sex research lab.

“I was interested in what happens in acute stress situations,” says Rosenbaum, who normally deals with post-traumatic stress.

“What happens to people’s need for connection, vitality and sexuality when there are horrible existential things going on that can affect their intimacy: going away to war, worrying about sirens, thinking about a disturbing video clip?”

The trio sent their questionnaire to 1,200 Israeli civilian adults who have been in a steady relationship at least six months. With an average age of 44, respondents represent a cross-section of religious, ultra-religious, traditional and secular Jews, mainly married heterosexual couples.

They’ve compiled their findings into two academic papers currently under review for publication.

Media images affect sexual function

Nearly half of respondents reported watching disturbing videos from the Hamas attacks several hours per day.

“They were almost addicted to watching war-oriented content,” says Lazar.

The amount of viewing time correlated with a self-reported decrease in sexual desire, arousal and orgasm.

“And we did not even include exposure to images of sexual violence, which became more known after we started our study,” says Gewirtz-Meydan. “But in our clinical practices, Talli and I hear a lot of people had difficult thoughts related to those images.”

Surprisingly, they found that media exposure to violent images was more predictive of decreased sexual functioning than was actual presence at the events or living near the areas where they took place.

Gewirtz-Meydan hypothesizes that this is because “our data is about people who were home, not people who were out there fighting.

“Soldiers are in a ‘doing’ situation and they come back home with a lot of sexual desire. The people on the home front are not in a doing place. They are getting pessimistic messages from television. So they have much more sexual inhibition. When you are in a doing situation, probably your mechanism for dealing with trauma is different than if you’re watching videos of it.”

Stress and sexual behavior

Regarding the war’s effect on sexual activity, survey results challenged assumptions that there would be a universal decline.

“We asked people to retrospectively report their frequency of sexual acts before and after, and if there’s been a change, why they feel it changed,” says Lazar.

“About 40 to 50 percent said their sexual behavior is unchanged, about the same said there was a decrease, and 3-5% said there was an increase.”

There weren’t significant differences between male and female respondents regarding changes in partnered behavior.

However, men were more likely than women to report changes (both increase and decrease) in solitary sexual activities – primarily masturbation and pornography.

Gewirtz-Meydan speculates that men could be “more sensitive to the effects of external stressors, or maybe tend to use this ‘sex channel’ to regulate their stress or to express it.”

Practical and psychological

Those reporting decreased partnered sexual activity cited both practical and psychological/emotional reasons. Emotional reasons were cited more often by both genders and especially by women.

Practical reasons included the possibility of an air-raid siren in the middle of having sex, or sleeping together with children in the safe room.

“We are in a state of hypervigilance, of being on guard, and these states are dissonant with intimacy,” says Rosenbaum.

Emotional reasons included sadness, depression, low desire, or feeling it’s wrong to enjoy sex when loved ones in uniform are fighting for their lives and hostages are still being held in Gaza.

“Each individual in the pair might react differently — one doesn’t feel right having sex at this time while the other really needs the intimacy,” Lazar says.

“That kind of clash can be very problematic but it’s important to know there are different legitimate normal ways of reacting to the situation and the partner shouldn’t take it personally.”

Gewirtz-Meydan wants people to know that it’s okay to decide to increase or decrease sexual activity in reaction to the war.

Increased sexual activity may be motivated by “a need to use sex for self-regulation or a way to cope with anxiety or just a need for intimacy and attachment in times of crisis,” she says.

Rosenbaum notes, “In previous studies of war veterans, we see a difference between desiring sex with a partner and using sexuality as a self-soothing mechanism. Many war veterans in our data report having a lot of difficulty with the vulnerability and connection necessary for partnered intimacy. They may be in a testosterone-driven place while their partner is looking for connection.”

Normalizing sexual health

Rosenbaum believes it’s significant that the study was approved and carried out so soon after the war started.

“We in Israel really value family and marriage. We are sexual-positive people. It’s important that we are normalizing the idea that sexual health is part of overall health.”

Rosenbaum cites longitudinal studies showing that after the Yom Kippur War 50 years ago, veterans and their spouses suffered greatly in reestablishing intimacy but never talked about it.

“Now we have an opportunity to talk about sexual health just as we talk about walking after a limb amputation,” she says.

Gewirtz-Meydan says the study is significant also for raising awareness of the link between trauma and sexuality.

“Trauma is very closely related to sexuality and sexual function,” she says, “yet people treated in trauma centers are never asked about sexuality. If people do experience difficulties in those areas, therapy is very effective and they should not feel guilty or embarrassed to raise sexual issues.”