Researchers in Israel have unlocked the complex mystery of why viruses sometimes stay friendly with their hosts and sometimes turn nasty.

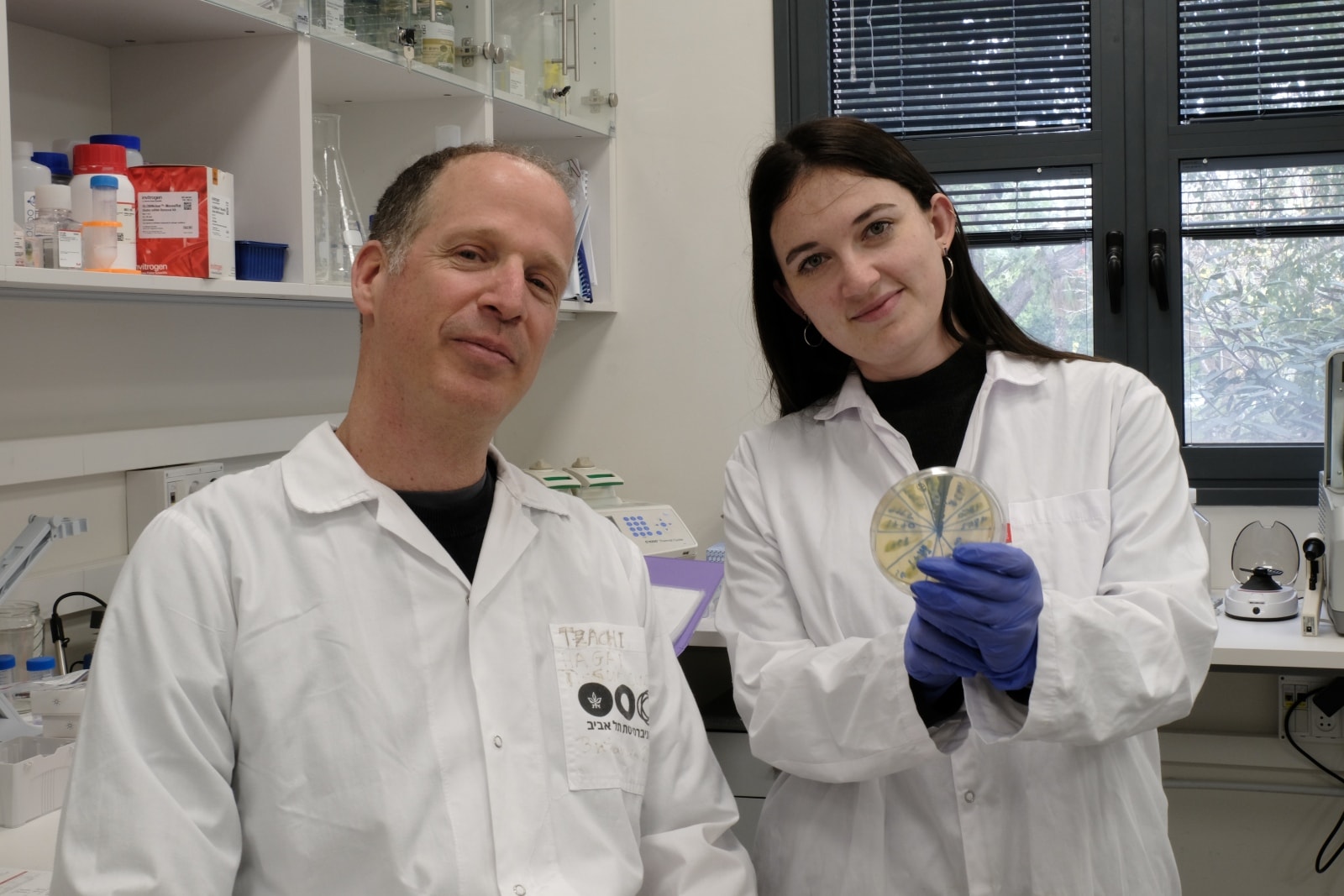

Their work at Tel Aviv University’s (TAU) Shmunis School of Biomedicine and Cancer Research reveals a new level of sophistication in what they call the “arms race” between a virus and its enemy.

They found that viruses – also referred to as bacteriophages or phages — succeed by lying dormant while weighing their options.

The phage effectively goes undercover, behaving in a friendly manner and even doing favors for its host as it bides its time; but what it’s actually doing is working out how healthy its host is, and whether it’s already under attack from a rival phage.

Though phages generally prefer to lie dormant, when they sense weakness they go for the kill.

“A phage can’t infect a cell already occupied by another phage,” said Avigdor Eldar, professor in molecular cell biology at TAU.

“If the phage identifies that its host is compromised but also receives signals indicating the presence of other phages in the area, it opts to remain with its current host, hoping for recovery,” he said.

“If there is no outside signal, the phage ‘understands’ that there might be room for it in another host nearby and it’ll turn violent, replicate quickly, kill the host and move on to the next target.”

“Some bacteria, such as those causing the cholera disease in humans, become more violent if they carry dormant phages inside them — the main toxins that harm us are actually encoded by the phage genome,” Eldar said, adding that it’s conceivable that phages could serve as replacements to antibiotics against pathogenic bacteria.

In addition, there are many human-infecting viruses that can alternate between dormant and violent modes, so phage research could lead to better understanding of viruses in general.

Understanding how phages reach their decisions could have far-reaching consequences for future research. A new study led by Polina Guler, a PhD student in Eldar’s lab, deciphers the mechanism that enables the virus to make these decisions.

“We discovered that in this process the phage actually uses a system that the bacteria developed to kill phages,” said Guler.

It turns that system to its advantage. If the phage doesn’t pick up a signal from any other phages — indicating that it has a good chance of finding new hosts — it switches to violent mode. It replicates and kills its host.

If, on the other hand, it senses high concentrations of signals — indicating a lower chance of success — it remains dormant.

Eldar concluded that “The research revealed a new level of sophistication in this arms race between bacteria and viruses.”

“Most bacterial defense systems against phages were studied in the context of viruses that are always violent. Far less is known about the mechanisms of attacks and interaction with viruses that have a dormant mode.”