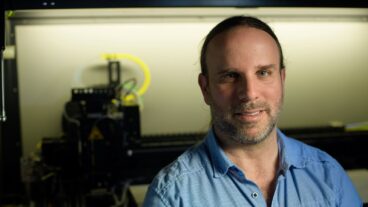

“Stroke is a pandemic,” says neurobiologist Lior Shmuelof of the department of cognitive and brain sciences at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU).

“In Israel, every year about 18,000 people have a stroke. A third die within a year, and most survivors suffer motor and cognitive impairment.”

And yet, he adds, “There is nothing new in recovery rates from brain damage like stroke. Rehab facilities look the same as they did 50 years ago.”

Part of the reason for this stagnation is a lack of translational research. This means scientific advancements at the academic lab level rarely make it into actual treatment protocols.

That was the motivation for establishing the Lillian and David E. Feldman Translational Neuro-Rehabilitation Research Lab about five years ago by BGU (the academic partner providing the basic science) and ADI Negev-Nahalat Eran rehabilitation village (the practical partner that identifies unmet needs and can test new approaches).

“Our idea was to do research that has an impact on the near future,” says Shmuelof. He now heads the multidisciplinary lab, whose first director was Simona Bar-Haim of BGU’s department of physical therapy.

Inspired by the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab in Chicago, the Israeli lab gets international requests for collaboration due to several unique features, says Shmuelof.

First, the Israeli medical system enables inpatient research during the critical months immediately after the stroke when recovery is most achievable.

“Unlike in the United States, where people are hospitalized for a maximum of two weeks after a stroke because of the insurance structure, in Israel they can be hospitalized two to three months and we can develop interventions that cannot be delivered elsewhere,” says Shmuelof.

Another unique feature is geographic. The lab won a US-AID grant to participate in the Middle East Regional Cooperation Project, which will help it scale its activities in Palestinian territories and neighboring countries.

Why do animals recover faster?

An essential question that has intrigued the lab is why post-stroke recovery is so much faster in animal models.

Monkeys, for example, regain full use of their limbs after only a few weeks, says Shmuelof.

The likely reason is that animals resume movement immediately after the injury, while human stroke patients spend a week to 10 days lying in a hospital bed and then two to three hours a day of rehabilitation.

Partly because hospitals are designed to prevent falls and partly because of a lack of personnel, “patients don’t get enough treatment and activity immediately after the damage,” says Shmuelof, who recently returned to the lab after several months of military reserve duty.

Technology = extra treatment hours

The Feldman Translational Research Lab did a study showing that 40 extra hours of post-stroke treatment improves upper-limb function.

Because hospitals and home rehab settings don’t have enough physical and occupational therapists to deliver those extra hours, the lab used innovative technologies to deliver and document the treatment under the guidance of Adi Tayer Yeshurun, head of research at ADI Negev.

“The technology needs to be highly engaging if [patients] have to practice for five hours at a time, focused on repetition and intensity,” emphasizes Shmuelof.

Some of the technologies were developed in collaboration with Switzerland-based MindMaze and Prof. John Krakauer, director of the Center for the Study of Motor Learning and Brain Repair at Johns Hopkins in Maryland.

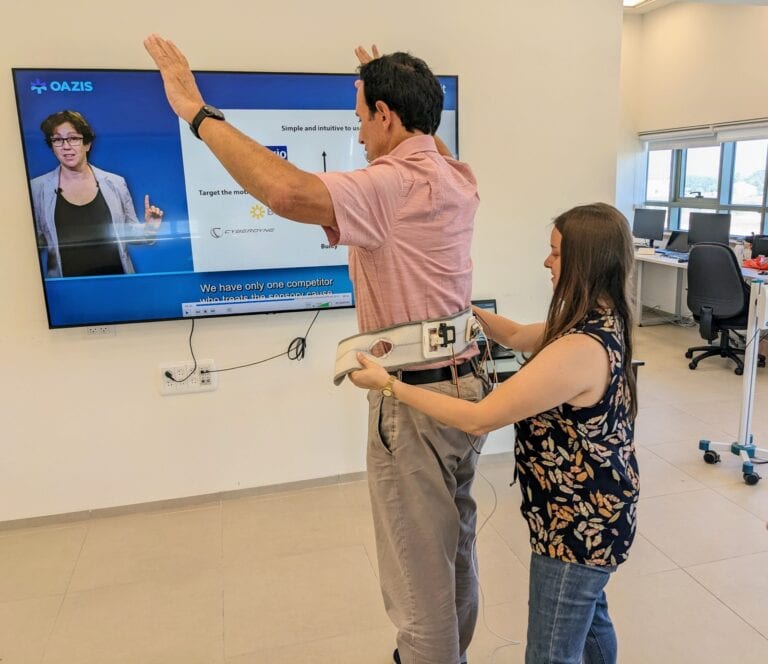

Other technologies were created inhouse, such as SenseGait, an AI-powered lightweight multisensory substitution belt that provides tactile stimulation on the lower back to help stroke patients regain walking ability.

Bar-Haim is the CEO and cofounder (with Prof. Ilana Nisky of BGU’s department of biomedical engineering) of SenseGait, which received funding from the Israel Innovation Authority.

Evaluation and monitoring

“Another aspect we work on is understanding the physical or cognitive deficits that underlie the impairments after stroke,” says Shmuelof.

“These impairments can keep people from going back to work and social activities. The most essential thing is to know what is driving the impairment — is it weakness, loss or motor control, muscle tension or cognitive deterioration? We use innovative approaches to better differentiate these components and find the right treatment.”

To more precisely evaluate impairment of upper limbs, the lab is validating its new method of taking a video of the subject and applying deep learning algorithms to quantify motion and coordination across the elbow, shoulder, wrist and fingers.

“Based on that, we can better capture their impairment and then in rehabilitation, use the same platform to read body posture in real time and provide gamified feedback.”

Sensors such as an acceleration meter, gyroscope and magnetometer gather data on how and how often patients move affected limbs during the majority of the day that they are outside the lab.

“Monitoring has always been complicated,” says Shmuelof.

“Smartwatches can track steps but not movements used in eating and other activities of daily life. The concern is that patients can show recovery in the lab but avoid using their affected arm in their daily activities.”

The lab is now studying the connection between cognitive impairment, motor learning and motor recovery in post-stroke patients to improve rehabilitation services.

Results so far indicate that a link between executive functions and language abilities in the immediate post-stroke stage isn’t seen in the later recovery stage.

Another current study aims to understand how sensory input – especially visual input — helps plan and guide the complex act of walking when an individual is in a healthy state and in impaired states.

Enriched environment

Shmuelof says studies in lab rats have proven the positive effect an enriched environment has on recovery.

For humans, he says, ADI Negev is “the perfect place for neuro-rehabilitation, not only in Israel but in the Western world, thanks to its enriched environment.”

Patients in the village’s recently opened Kaylie Rehabilitation Medical Center, as well as 170 residents with disabilities who live in the village full time, can get outdoors every day to enjoy the gardens, farm, hydrotherapy and sports therapy complexes, therapeutic horse stable and petting zoo.

This provides a more calming and enriching environment for rehab, according to Bar-Haim.

As the only rehabilitation hospital in southern Israel, Kaylie Rehabilitation Medical Center is providing inpatient and outpatient care to more than a dozen IDF soldiers and dozens more civilians in the aftermath of October 7.

Transformational

The Feldman Translational Research Lab, located in the medical center, is staffed by ADI Negev clinicians, research assistants and coordinators along with undergraduate and graduate students from various BGU departments.

ADI Negev-Nahalat Eran is a Jewish National Fund USA affiliate. Much of the lab’s funding is from American donors like Joan and Bob Oppenheimer of New Jersey.

“When we visited in April 2023, we had the opportunity to see the Translational Lab,” Joan Oppenheimer tells ISRAEL21c.

“My mom, who was with us, participated in one of the gamifying systems that they use as part of their state-of-the-art rehabilitation tools. Not only is it transformational, but it displayed a way to put quick and painless recovery into the hands of the patients, hopefully allowing a significant increase in therapy sessions that can be done with, but most importantly without, the aid of a professional.”