Immunotherapy holds perhaps the greatest promise for fighting cancer in the 21st century. Rather than bombarding the body with toxic chemicals, as in chemotherapy, immunotherapy utilizes the immune system to neutralize malignant tumors.

The only problem: It only works in about 20 percent of patients with solid tumors.

The reason is straightforward, but still represents a vexing roadblock for cancer researchers: Tumors are not an infection coming from outside but an internal malfunction of the body’s own cells, which begin to replicate out of control.

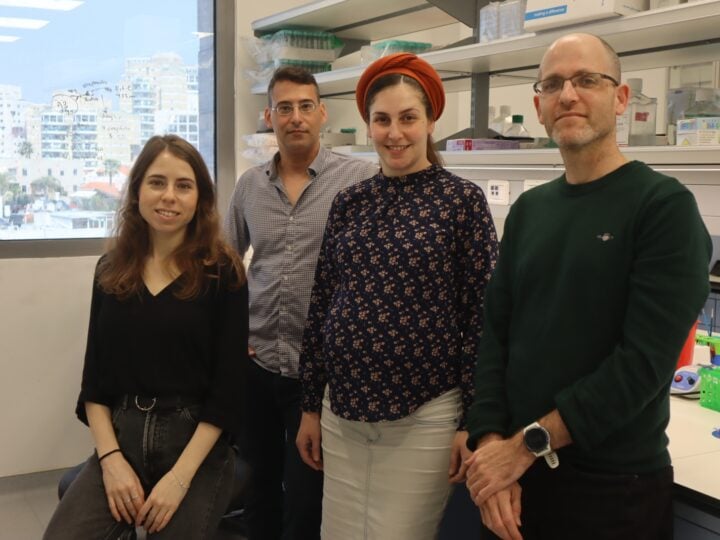

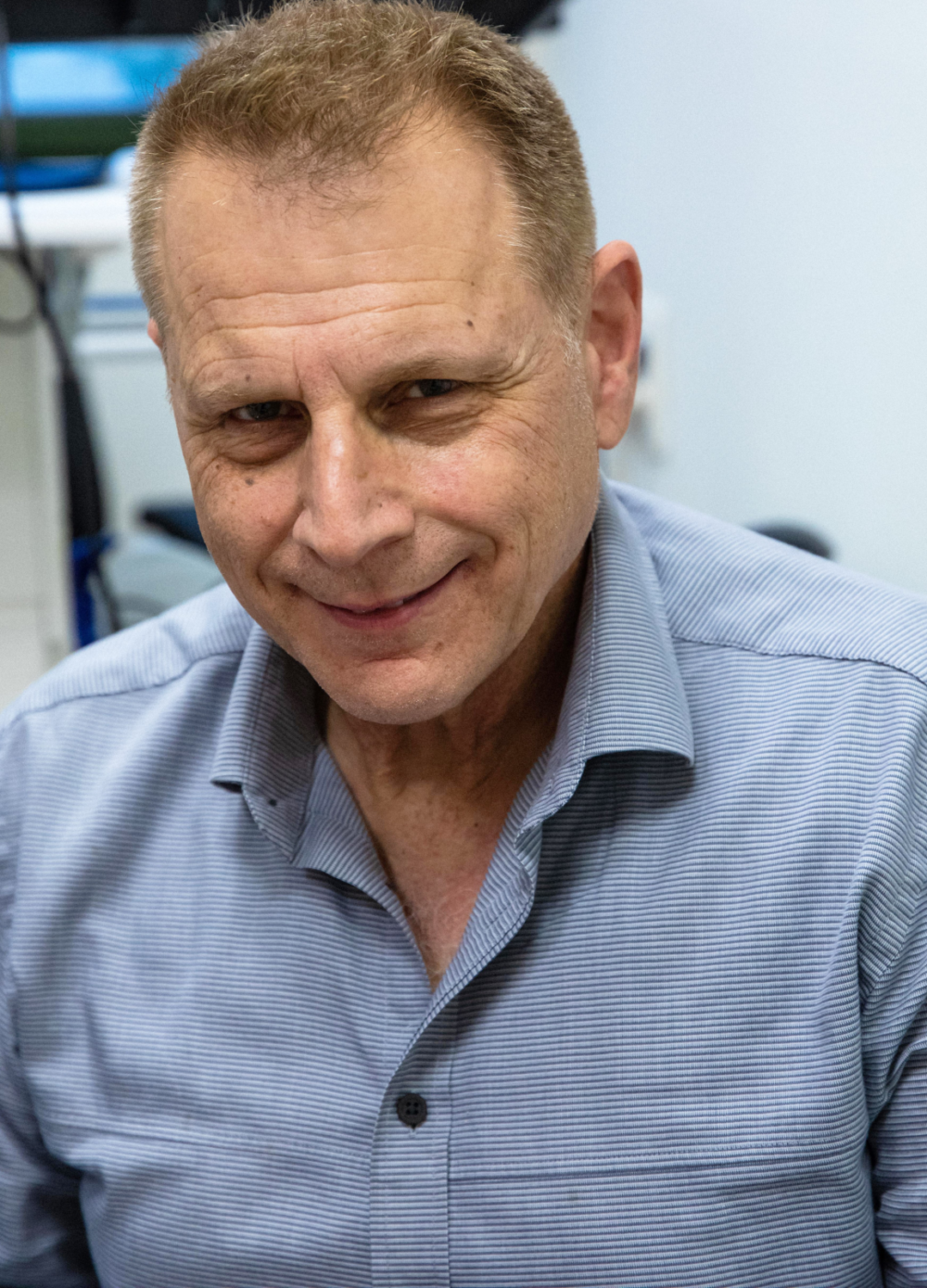

“Cancer looks like us. It’s hard for the immune system to identify,” explains Dr. Asher Nathan, CEO of NeoTX, a Rehovot-based startup developing a novel way of knocking out tumors – by coating them in bacteria.

“Unlike with cancer, our bodies are finely tuned to attack bacteria,” Nathan says. “Bacteria is a billion years old. Our immune systems have had a long time to figure out how to effectively neutralize bacterial infections. That’s why you don’t wake up in the morning with a cold and think, ‘I’m going to die.’”

Cancer, of course, is a very different story. Compared with bacteria, “cancerous tumors are like the new kid on the block,” Nathan notes.

NeoTX is not Nathan’s first foray into medical technology; after immigrating to Israel 40 years ago from Chicago, he founded IntelliGene and EvoRX, two biotech companies formed around technologies he invented.

For NeoTX, Nathan identified and licensed a drug developed by the Swedish company Active Biotech called naptumomab estafenatox (NAP).

NAP is composed of two proteins: a genetically modified “superantigen” and an antibody that latches onto a tumor via a molecule called 5T4 found primarily on tumors.

A superantigen is a bacterial derivative that elicits a strong antibacterial immune response. NeoTX calls its technology “Tumor-Targeted Superantigen” or TTS.

Once NAP’s 5T4 antibody has attached itself to a tumor, the superantigen “reprograms” the immune system to mount an antibacterial response against the bacteria as well as the tumor.

“The concept behind this drug is, let’s coat the tumor with a bacterial molecule so that the immune system will go into ‘Defcon 1’ and attack the tumor as if it’s bacteria,” Nathan says.

The secret weapon

Once the immune system knows what to look for, it sends in the body’s secret weapon: killer T-cells.

The T-cells identify the bacteria-coated tumors, then start to create an army of cells primed to attack any superantigens they find. Nathan recommends the video below to see how T-cells work; they “grope around like a blind robot” and after hitting a superantigen, punch a hole in the cell … then insert a molecule that causes the cell to explode.”

It’s a fine balance. When fighting a bacterial infection, “the body can go crazy,” Nathan notes. “You can get a high fever that exhausts the immune system. That’s how the bacteria continue to fight. We genetically engineered our superantigen to be safer. It doesn’t generate as strong a response, but it still creates a very powerful immune reaction.”

Targeting bacteria is smart for another reason: Part of how tumors succeed in evading the body’s defenses is by releasing chemicals that weaken the immune response.

“Anything we do nearby the tumor becomes problematic,” Nathan says. But with NAP, “the tumor-killing T-cells are created far from the immune-suppressed tumor site.” Only then do they begin their journey to seek out and destroy the tumors.

Moreover, when the immune system encounters a superantigen bound to a tumor, it modifies the suppressive micro-environment around the tumor so that the body’s natural defenses are better able to kill it.

“This creates a natural, holistic and profound immune response,” Nathan says.

Reboots the immune system

But the best may be yet to come.

“When we’ve tested this drug in animals, we find that even when you try to reintroduce cancers into, say, a mouse that’s been cured by the technology, it doesn’t stick,” Nathan says.

“None of the mice that were ‘rechallenged’ got cancer again. The drug ‘wakes up’ the immune system – at least in mice – and we don’t need any more drug.”

Nathan likens it to the reboot function on a computer. “The drug reboots the immune system so it can do what it natively needs to do – remove the suppressive environment and kill as many tumor cells as possible. Then, the T-cells can go after more targets.”

NeoTX’s bacterial coating approach is currently in a Phase I trial in Israel and, based on encouraging results, has begun a Phase 2 trial in the United States with 30 patients.

One patient has non-small cell lung cancer that had metastasized to the liver. “That’s a death sentence, usually within four months,” Nathan says. The patient received NeoTX’s drug over a decade ago (prior to it being licensed from Active Biotech). “She lived for 11 years and died of something else, not her cancer.”

NAP plays particularly well with checkpoint inhibitors, another type of cancer treatment that aims to tamp down “checkpoints” created by the cancer that essentially trick the T-cells into thinking the tumor is a friend.

“It’s like a secret handshake in a college fraternity,” Nathan quips.

If the handshake were inhibited, so to speak, the T-cells would see the tumor for what it is – very much not a friend – and could attack. Combining NAP with a checkpoint inhibitor “allows our drug to kill more tumor cells,” Nathan says.

AstraZeneca collaboration

Pharma giant AstraZeneca is collaborating with NeoTX on the former’s own checkpoint inhibitor technology. The hope is that patients who don’t normally respond will have greater success in beating back their cancers.

Developing and commercializing any new drug can take up to 15 years and many millions of dollars. NeoTX has raised around $80 million so far. Nathan is optimistic that if NAP passes Phase 2 and 3 trials, it could hit the market as early as 2027.

While the technology has so far been tested on solid lung, esophageal and urethral cancer tumors, patients with blood cancer such as lymphoma and leukemia could benefit, too – in particular those who are candidates for CAR-T, a promising treatment that involves removing T-cells from a patient, engineering them for maximum killing ability in a lab, then reinjecting them.

CAR-T, a form of immunotherapy, tends to work well for blood cancers but poorly for solid tumors. That’s another aim for NeoTX – to provide a pharmaceutical complement that will allow CAR-T to be effective outside the blood cancer domain.

Immunotherapy has become a crowded field. “If you look at all the companies that are trying to elicit an immune system response, there are probably 1,000 out there. But for the specific mechanism we’re trying, it’s zero,” Nathan notes.

“One of our investors said to us, ‘You’re either geniuses or you’re crazy.’ I replied, ‘What makes you think it’s one or the other?’”

NeoTX has no shortage of geniuses. Roger Kornberg, the 2006 winner of the Nobel Prize in chemistry, is the company’s chief scientist (as well as a long-time collaborator with Nathan in his previous endeavors).

Michael Levitt and Arieh Warshel, who shared a Nobel in chemistry in 2013, are advisers. Dr. Marcel Rozencweig, a medical oncologist and 18-year veteran of pharma company Bristol Myers Squibb, where he was head of global oncology, is NeoTX’s president.

Recently, the head of global clinical oncology at Bayer pharmaceuticals, Dr. Scott Fields, joined NeoTX as chief medical officer.

“It is extremely rare that someone as high up as Scott Fields would leave pharma to work in such a small company,” Nathan tells ISRAEL21c. “It is even more rare that he would come to a company based in Israel.”

Cancer, sadly, isn’t going away anytime soon. “The average person develops around five cancerous or pre-cancerous cells a day,” Nathan notes.

“Our bodies are very efficient at killing, such that most people don’t get a new cancer every day. Our drug could level the playing field so the body can do what it’s meant to.”

For more information, click here