When you think of Neanderthals, images of barrel-chested, hunched-over cavemen tend to spring to mind. But that’s not the case, according to new research published recently in the journal Nature Communications and conducted in Israel, Spain and the United States.

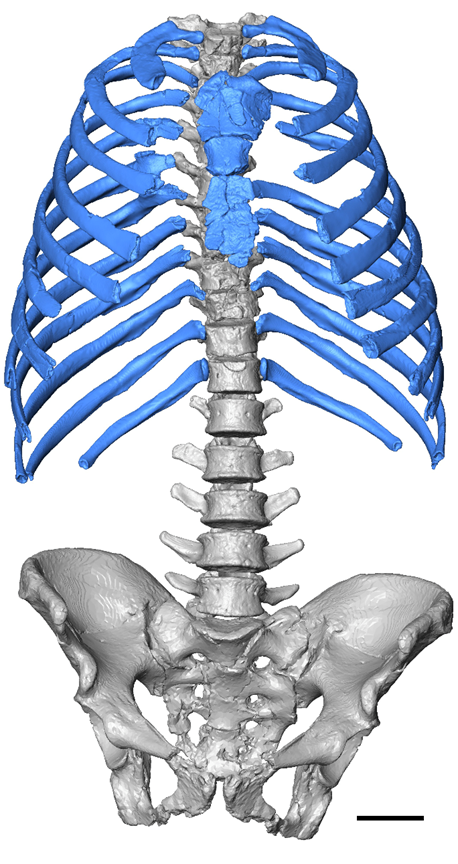

The researchers, led by Ella Been of Israel’s Ono Academic College, did the first 3D virtual reconstruction of the ribcage of the most complete Neanderthal skeleton unearthed to date.

That skeleton was found in 1983 in the Kebara Cave in Israel’s Carmel mountain range and is estimated at between 59,000 and 64,000 years old. Neanderthals lived in Eurasia sometime between 450,000 years ago and 45,000 years ago.

The researchers, who dubbed the skeleton “Moshe” after Israeli archeologist Moshe Stekelis, focused on the shape and dimensions of the Neanderthal thorax – the rib cage, sternum and upper spine – which forms a cavity to house the heart and lungs.

“The shape of the thorax is key to understanding how Neanderthals moved in their environment because it informs us about their breathing and balance,” says Asier Gómez-Olivencia, a paleontologist at the University of the Basque Country in Spain, who participated in the research.

The most surprising finding: Neanderthals not only didn’t walk hunched over, they stood up taller than modern humans with a straighter spine and an entirely different rib structure.

In Neanderthals, the ribs connect to the spine in an inward direction, which forces the chest cavity outward. The lumbar curve that is part of the modern human skeletal structure is mostly missing.

This rib arrangement, along with a lower thorax that is wider than in modern humans, allowed Neanderthals to rely more on the movement of the diaphragm for breathing. Modern humans breathe both by moving the diaphragm and expanding the rib cage.

As a result, it appears that Neanderthals could breathe in more deeply without requiring a larger chest or lungs than modern humans, as had previously been assumed.

The thorax and rib arrangement found in the Neanderthal skeleton would also have placed “the spine more inside the thorax, which provides more stability,” says Prof. Patricia Kramer of the University of Washington’s department of anthropology.

“The differences between a Neanderthal and a modern human thorax are striking,” says Markus Bastir, senior research scientist at the Laboratory of Virtual Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History in Spain.

Who was Moshe?

The 3D virtualization was a painstaking process.

“We had to CT scan each vertebra and all of the rib fragments individually and then reassemble them in 3D,” explains Alon Barash of the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Israel’s Bar-Ilan University.

“Neanderthals are closely related to us with complex cultural adaptations much like those of modern humans, but their physical form is different from us in important ways,” Been added. “Understanding their adaptations allows us to understand our own evolutionary path better.”

What does all this mean for how “Moshe” lived? For what physical demands did he need such powerful lungs? What does it tell us about how Moshe moved and the environment in which he lived? Did any of Moshe’s physical traits make him more or less adaptive to the climate change happening in Eurasia during the Neanderthal period?

The researchers will turn their investigation to these questions next.

The team previously looked at the shape of the Neanderthal spine in 2016, with research published in the book Human Paleontology and Prehistory. The new virtualization was the first time they had done a 3D work-up on the thorax.

The remains of Moshe are housed at Tel Aviv University.