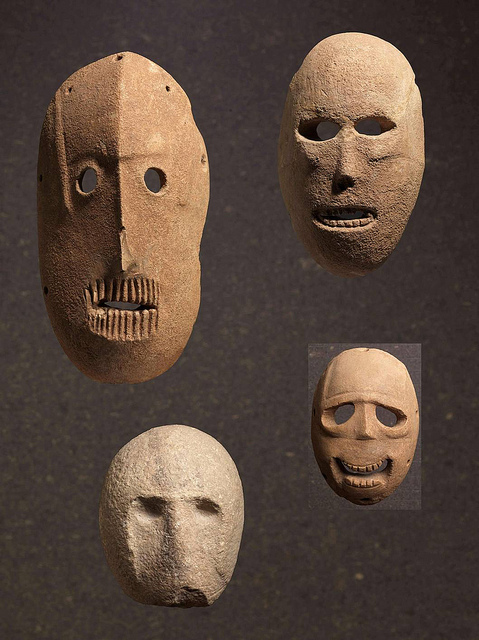

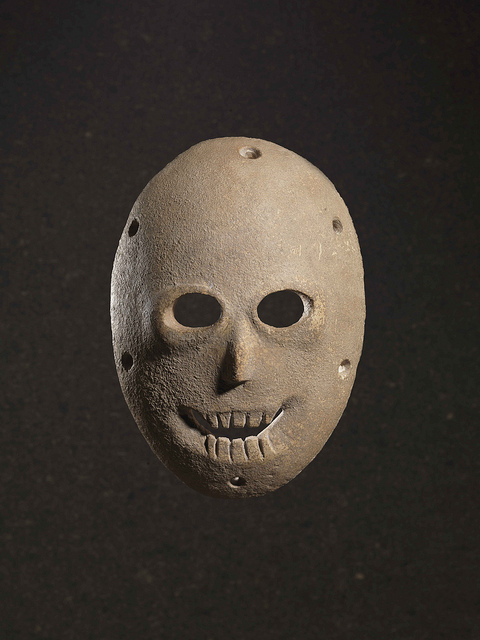

Nine thousand years ago, a village of Neolithic farmers thrived in the Judean Desert and hills in the ancient Land of Israel. Using primitive stone tools, they fashioned face masks of stone – perhaps as a form of ancestor worship, though nobody knows for sure.

A combination of good fortune, anthropological sleuthing and cutting-edge lab technology has come together to present 12 of these priceless masks, together for the first time since their creation, at Jerusalem’s Israel Museum.

The groundbreaking exhibition “Face to Face: The Oldest Masks in the World” opened March 11 and runs through September 13, 2014.

“This is the fruit of 10 years of research, lab work and scientific work to find the masks, compare them and understand more about these unbelievably rare objects,” said Debby Hershman, the museum’s curator of prehistoric cultures, during a press tour of her laboratory before the exhibition opened. Wearing white cotton gloves, she held up four of the masks to show journalists.

As an archeologist and anthropologist, Hershman surmises that the two- to four-pound masks, each strikingly similar yet distinct in shape, size and features, may have been used in healing and magic cultic rituals.

“Did they wear them or hang them on the wall? With our modern technological methods, we determined that they were made to be worn, and were worn, most probably by shamans,” she said.

One, two, 12

For many years, the Israel Museum has held in its collections two Neolithic stone masks. One was acquired in the 1970s, originally found by a farmer in Horvat Duma – which turned out to be the site of one of the most ancient villages ever discovered — in the Judean Hills. The other was unearthed by an archeological team, including Hershman and Tel Aviv University Prof. Yuval Goren, in the 1980s in a cave at Nahal Hemar in the Judean Desert.

“Luckily for us, they made these masks from stone, because probably other groups made similar masks from other materials that did not last,” Hershman said. The stone was coated with a paint-like patina that made their period of origin easy to identify.

“Ten years ago, I was preparing the two masks for exhibition and found in our archives three old black-and-white photos of similar masks that were labeled as being from a private collection,” she related. “Nobody knew anything about it.”

However, when museum director James Snyder eventually saw the photos, he recognized them from the collection of Michael and Judy Steinhardt in New York.

The Steinhardts agreed to transport their masks to the museum, where Hershman and Goren, who is an expert in comparative microarchaeology, could study them. Goren used the computerized archaeology laboratory at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to conduct 3D analysis of the objects.

“Debby and Yuval have determined that these masks are all from the same region in the Judean Hills and nearby in the desert, all from the same period and presumably all served a similar function,” Snyder told reporters. “It’s a great opportunity to start to unlock the mystery of why these were made and for what purpose.”

Snyder said the masks “represent the first attempts of man to fashion with his hands, out of physical material, something that was a reflection of himself or in relation to something outside himself. In our [museum’s] narrative, that’s all about entering that very long highway that starts with the first glimmerings of existential reflection and a long time later leads to polytheism, monotheism, Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Along that highway there was always, for us, that special moment because of these two amazing masks found within a 20-mile radius of each other in the Judean Hills, clearly related to a ritual that we don’t know very much about.”

x