Imagine that you cannot talk. You know what you want to say, but your speaking muscles are paralyzed because of a stroke, nerve disease or other medical condition.

Technion-Israel Institute of Technology researcher Ariel Tankus does not have a magic wand to cure the problem, but the 37-year-old computer scientist has spent two years working on a complex brain-machine interface that could give the power of speech to people unable to express themselves.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

This super-advanced technology would articulate letters or words by decoding brain activity triggered by the patients thinking of the sounds they wish to make.

The beginnings of the research were recently described in the scientific journal Nature Communications by Tankus and his research partners, Prof. Shy Shoham from the Technion and Prof. Itzhak Fried of the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), where Tankus did his postdoctoral research.

Tankus tells ISRAEL21c that he has been investigating brain-machine interface possibilities since 2005. Four years later, he paired with Shoham and shifted his focus to speech – a complex and challenging area to study in the brain.

“Our experiments began a long time before meeting the patients,” Tankus says. “First we designed what we would ask patients to do, and decided to focus on vowels in order to build speech from vowels to simple syllables and hopefully to combine them later into words and maybe sentences. The next step was preparing the software that will correlate the relevant recorded information.”

Recognizing speech from brain activity

But how to find volunteers for such a study? A perfect opportunity presented itself at UCLA Medical Center. Patients with epilepsy unresponsive to medication were having electrodes surgically implanted in their heads for a week or two, so that doctors could record brain activity on the cell level during seizures. Many of the volunteers in this study were happy to participate in Tankus’ research while the electrodes were in place anyway.

“We explained what these experiments aim to accomplish, and the vast majority were very willing to help us develop technology to help paralyzed persons in the future,” says Tankus.

At their hospital bedside, he instructed volunteers to say a vowel sound – “ah,” for example – every time they heard a beep. By synchronizing the software on his laptop with the neural recording equipment already hooked up to the patient, Tankus recorded brain activity accompanying each “beep-ah-beep-ah” sequence. He also recorded activity when the patient said a consonant-and-vowel syllable.

Next, he coded the data so the software could predict — based only on brain activity and not a sound recording — what sound the person spoke. Sure enough, when a patient said “ah,” the computer played back “ah.”

“We continuously improve our ability to predict the vowel sounds,” says Tankus, who flew back and forth from Israel to California several times to complete the experiments. “Right now we have the machine, and we suggested a new algorithm for doing this prediction in an article coming out soon in the Journal of Neural Engineering.”

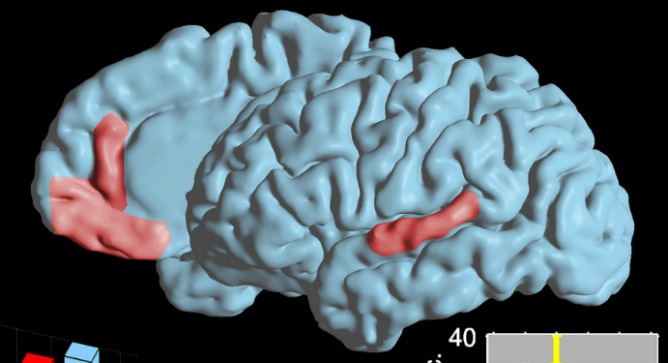

The researchers mapped out the mathematical arrangement of how the various vowel sounds are represented in areas of the brain, connecting the brain representation with the anatomy and physiology of vowel articulation.

Computer predicts imagined vowel sounds

In the next stage, the brain-machine interface predicted and played back a vowel sound that the patient thought about after hearing the beep, but did not utter out loud. Tankus reports that the patients were “surprised that they managed to make the computer speak instead of them.”

In his lab in Haifa, Tankus is fine-tuning the software to decode consonants from brain activity as well. Eventually he hopes to combine vowels and consonants into more complex speech structures.

Tankus and his research partners plan to bring the electrode technology to Tel Aviv’s Sourasky Medical Center to serve epilepsy patients in Israel, and at the same time offer them the opportunity to be part of continuing experiments with the brain-machine speech interface.

“There are diseases in which the patient’s entire body is paralyzed; he is effectively ‘locked in’ and is unable to communicate with the environment, but his mind still functions,” explained Shoham, who heads the Neural Interface Engineering Laboratory in the Technion Department of Biomedical Engineering. “Our long term goal is to restore these patients’ ability to speak using systems that will include implanting electrodes in their brains, decoding the neural activity that encodes speech, and sounding artificial speech sounds.”