Starting in the 1970s, the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research starting collecting skin cells of various animals and putting them into deep freeze. While Jurassic Park might always stay science fiction, the notion was that one day the technology would exist to bring endangered animals — or at least their DNA — out of the cryogenic freezer and back to life.

That time has come, and an Israeli scientist is deeply involved in this remarkable achievement that Discover magazine called one of the top 100 stories of 2011.

Today there are cells of more than 800 kinds of animals in storage at the so-called Frozen Zoo, and two animals now have more hope for survival thanks to advances in stem-cell research by Dr. Inbar Friedrich Ben-Nun and her team at the Scripps Research Institute in California, overseen by lead researcher Dr. Jeanne Loring.

Some of the frozen genes could replenish animal populations at risk for “inbreeding depression,” a negative consequence of reproduction among few individuals — the same basic problem involved in the offspring of close family members.

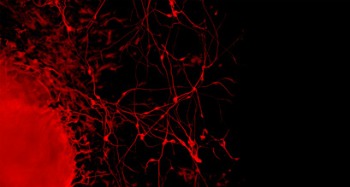

As part of her post-doctoral research, the Israeli Ben-Nun took skin cells from both a non-living drill primate and from the almost-extinct northern white rhinoceros, and grew them into viable stem cells. The research was published in the journal Nature Methods in September.

“We are the first to publish on the generation of pluripotent stem cells from endangered species,” she tells ISRAEL21c.

Pluripotent stem cells are capable of differentiating into one of many cell types. As a theoretical next step, researchers could create a protocol for programming the cells to become gametes — sperm or eggs — that could then be “mated” with existing animals, introducing new genetic material into the gene pool.

The technology is there, but it’s expensive, Ben-Nun explains, adding that more money desperately needs to be put into researching stem cells of the animal kingdom in order to preserve endangered species.

A new way to conserve nature

The northern white rhinoceros was chosen because it is one of the most endangered species on the planet. There are only seven animals still in existence, two of which reside at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

Ben-Nun was determined to assure the future of this creature. “I knew we could do it. We tried one species, the drill, and then went to a more exotic species. There are no DNA sequences for either, but now there are labs very interested in taking this on,” she says. Her research will open the doors to this novel conservationist approach.

The idea began with the keeper of the Frozen Zoo, Dr. Oliver Ryder. He approached Scripps wondering if his animal skin cell collection could be used in new research to save endangered species.

There are still various unknowns, cautions Ben-Nun. One of them is whether in-vitro fertilization will work with drills and white rhinos.

“If we can get viable cells, the sky’s the limit to developing the technology as long as we have the money to do it,” she says. As of yet, “there is no protocol to take stem cells and differentiate them into sperm, but once we have that technology we can proceed.”

“My main goal is to show that we can apply cellular programming to saving endangered species. Thirty years ago they didn’t know it could happen, and in another 30 we don’t know where we will be.”