Though famous for its pioneering origins and innovative spirit, Israel has a few surprises that even many locals are unaware of. Among these is the cluster of authentic cowboys in the Golan Heights.

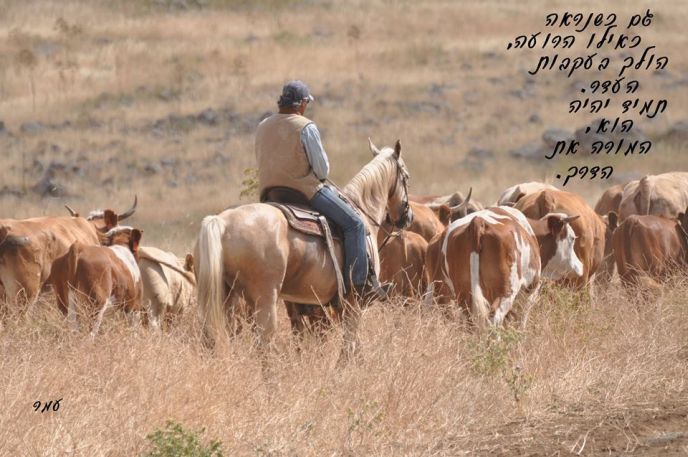

ISRAEL21c was treated to a tour of one of a handful of ranches in the north of the country. At Kibbutz Merom Golan, cattle roam wild and cowboys on horseback herd them from pasture to pasture on 34,000 dunams (8,400 acres) of land.

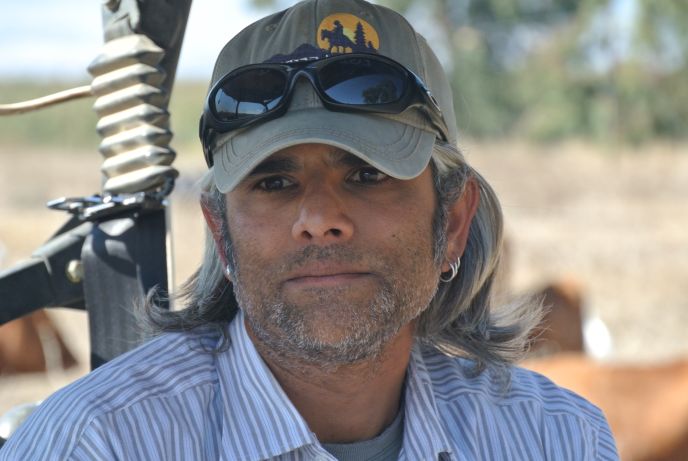

Erez Ashtamker, who runs the ranch, was born and raised on the kibbutz. He smiles when asked why he is wearing a baseball cap and sturdy shoes, rather than a cowboy hat and boots like those tacked to a wall in the shack that serves as an office and kitchen.

“You mean, like in Brokeback Mountain?” he asks. “Yes, the media always want us to pose as though we’re in a movie about the American West, even though we’re in the Middle East.”

His assistant, Shay Zerbib, who owns a private ranch in the area, jumps in to answer. “We are Israeli cowboys,” he says, almost indignantly.

Both 35-year-old Ashtamker and 41-year-old Zerbib are “packing heat” in hip holsters. Ranchers in the Golan must safeguard against the constant threat of cattle theft and predators such as wolves and jackals.

Shooting the animals is only a last resort, as wolves are a protected species in Israel and only with permission from the Israel Nature and Parks Authority are the cowboys allowed to shoot or trap them, even when catching them in the act of attacking a cow or calf. Poisoning is forbidden, since it has long-term repercussions on the food chain.

Fences are another deterrence method.

“But the wild animals have found ways around this, by digging under or climbing over them,” says Ashtamker. “So some of the ranchers in the area keep building higher and higher fences, and electrifying them. It’s crazy.”

The key protectors of the 1,100 head of cattle on Merom Golan – of the total 12,000 in the Golan as a whole — are dogs.

An Israeli innovation

The practice of using dogs to protect cattle, it turns out, is an Israeli innovation introduced by veteran Kibbutz Merom Golan member Omer Weiner in 1981. Weiner is now a pensioner, yet frequents the ranch daily to impart advice to his younger protégés.

He figured out that Pyrenees, dogs traditionally deployed in Europe to guard sheep, could do the same for cattle. “This is because they bond with a particular animal, rather than with their owners,” explains Weiner, a self-described “cowboy poet.”

Indeed, while moving from paddock to paddock assisting in the branding and ear-tagging of the newborns, Weiner — an expert on the economy and ecosystem of the Golan – composes poems in his head. He then writes them down and pairs them with photographs he takes of nature scenes in the area.

It is not what one expects from a cowboy, even a retired one. But there is an idealistic aspect of the vocation.

Zerbib explains: “It began with Zionism. Even the state of Israel’s definition of ‘cowboy’ (boker in Hebrew) is someone who ‘safeguards national lands.’ The fact is that if we didn’t settle here, somebody else would.”

The state leases the land to the ranchers, and governmental agencies such as the Ministry of Agriculture oversee and aid their endeavor.

“We’re certainly not in it for the money,” says Ashtamker, who explains that only seven percent of the beef consumed in Israel comes from cows that graze in pastures; the rest are farm-fed or imported.

Premium beef

Zerbib hopes to make the livestock trade more lucrative by organizing the other four or five ranches in the Golan to market a premium brand of meat to upscale Israeli restaurants.

“What we lack in quantity, we want to make up for in quality,” he says.

He adds that the move to vegetarian and vegan diets by some health-aware Israelis has not put a damper on the demand for beef. “Everybody watches [the cooking-competition reality TV program] Master Chef these days, so the purchase of meat has not decreased.”

Nor has unrest on Israel’s northern borders with Syria and Lebanon affected the livestock business. While we visit the pastures and watch new mothers suckle their calves, the quiet is disrupted suddenly by a series of loud “booms” from gunfire and other weapons in the vicinity.

Ashtamker barely blinks. The animals also take it in stride.

“We are all used to that noise,” he says, pointing to a nearby IDF base that conducts regular military exercises.

The cows – or the fewer number of bulls there to impregnate the herd – also seem undisturbed by our driving through the pasture in an open ATV as Ashtamker and the other cowboys make their rounds on horseback in the early hours of the morning.

He and the others say that they do get attached to the cattle they raise, which makes it hard to sell them for slaughter. “But up until the moment they are sold – each for about NIS 5,500, a bit under $1,500 – we treat them with great care, medically and otherwise.”

The same goes for the horses.

According to Weiner, “Even when they are ‘put out to pasture’ for age or infirmity, we keep them here as ‘pensioners’ under humane conditions. They gave us their all throughout their lives, and we owe it to them.”

Fighting for Israel's truth

We cover what makes life in Israel so special — it's people. A non-profit organization, ISRAEL21c's team of journalists are committed to telling stories that humanize Israelis and show their positive impact on our world. You can bring these stories to life by making a donation of $6/month.