The September 6 cover story of Science reports on a Tel Aviv University study warning of a phenomenon that could lead to extinction for certain reef-building corals in the Red Sea’s Gulf of Eilat.

Coral reefs are among the most diverse and productive ecosystems on our planet.

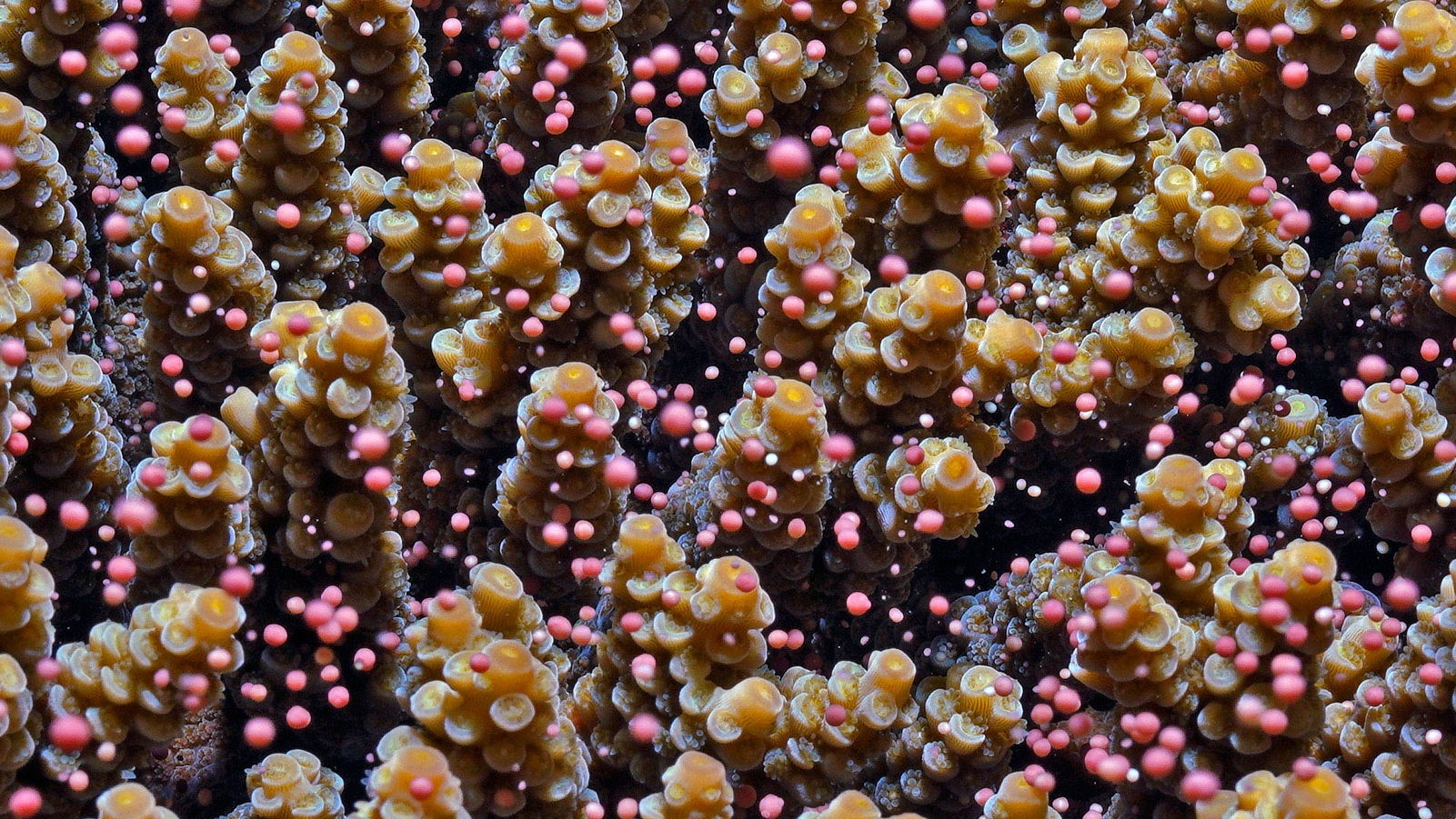

However, due to climate change and other human stressors, the highly synchronized “broadcast” spawning — the simultaneous release of eggs and sperm into open water — reef-building corals have completely lost their vital synchrony over time, dramatically reducing chances of successful fertilization.

According to the research, led by Prof. Yossi Loya and PhD candidate Tom Shlesinger of TAU’s School of Zoology, the breakdown in coral spawning synchrony puts these types of corals under threat of extinction.

‘Greatest orgy in the world’

“Coral spawning, often described as‘the greatest orgy in the world,’ is one of the greatest examples of synchronized phenomena in nature,” said Loya.

“Once a year, thousands of corals along hundreds of kilometers of acoral reef release their eggs and sperm simultaneously into the open water, where fertilization will later take place. Since both the eggs and the sperm of corals can persist only a few hours in the water, the timing of this event is critical.”

Successful fertilization, which can take place only within this narrow time window, requires a precise spawning synchrony.

And that synchrony relies on environmental cues including sea temperature, solar irradiance, wind, the phase of the moon and the time of sunset. Pollution and climate change affect those cues.

Nighttime surveillance

In 2015, the Tel Aviv University researchers beganlong-term monitoring of coral spawning in the Gulf of Eilat (also called the Gulf of Aqaba).

Over four years, they performed 225 nighttime field surveys lasting three to six hours each during the annual coral reproductive season fromJune to September. They recorded the number of spawning individuals of each coral species.

“We found that, in some of the most abundant coral species, the spawning synchrony had become erratic, contrasting with boththe widely accepted paradigm of highly synchronous coral spawning and with studies performed on the exact same reefs decades ago,” said Shlesinger.

The scientists then investigated whether this breakdown in spawning synchrony translated into reproductive failure.

They mapped thousands of corals within permanent reef plots, then revisited these plots every year to examine and track how many corals of a given species had died compared to the number of new juvenile corals recruited to the reef.

“Although it appeared that the overall state of the coral reefs at Eilat was quite good and every year we found many new corals recruiting to the reefs, for those species that are suffering from the breakdown in spawning synchrony, there was a clear lack of recruitment of new juvenile generations, meaning that some species that currently appear to be abundant may actually be nearing extinction through reproductive failure,” said Shlesinger.

“Several possible mechanisms may be driving the breakdown in spawning synchrony that we found,” Loyasaid.

“For example, temperature has a strong influence on coral reproductive cycles. In our study region, temperatures are rising fast, at a rate of 0.31 degrees Celsius per decade, and we suggest that the breakdown in spawning synchrony reported here may reflect a potential sublethal effect of ocean warming.

“Another plausible mechanism may be related to endocrine-disrupting pollutants, which are accumulating in marine environments as a result of ongoing human activities that involve pollution.”

Shlesinger said that regardless of the exact cause leading to these declines in spawning synchrony, “our findings serve as a timely wake-up call to start considering these subtler challenges to coral survival, which are very likely also impacting additional species in other regions.”

On a positive note, he added, “Identifying early-warning signs of such reproductive mismatches will contribute to directing our future research and conservation efforts toward the very species that are at potential risk of decline, long before they even display any visible signs of stress or mortality.”