An Israeli-made mobile app alerted the parents of a 13-year-old boy in Phoenix, Arizona, that their son was in a sexual relationship with his 27-year-old teacher.

The app from Ra’anana-based Sentry Parental Control flagged suspicious content on the teenager’s phone, including sexually explicit text messages and nude photos, which led to the arrest of the teacher earlier this year. The boy’s parents expressed the fear that, without the app, the relationship might have continued.

Michael Druker began developing the AI-based automated tools that would become Sentry when his own son – then only eight – demanded a cell phone. Druker, a software engineer who had been working on image-recognition technology, says he knew “from working in this industry the risks children are exposed to from social media and messaging apps.”

Druker looked around to see if there were any software programs to monitor what kids do on their devices. “There were no solutions,” he realized. So, together with a partner, he decided to build one himself.

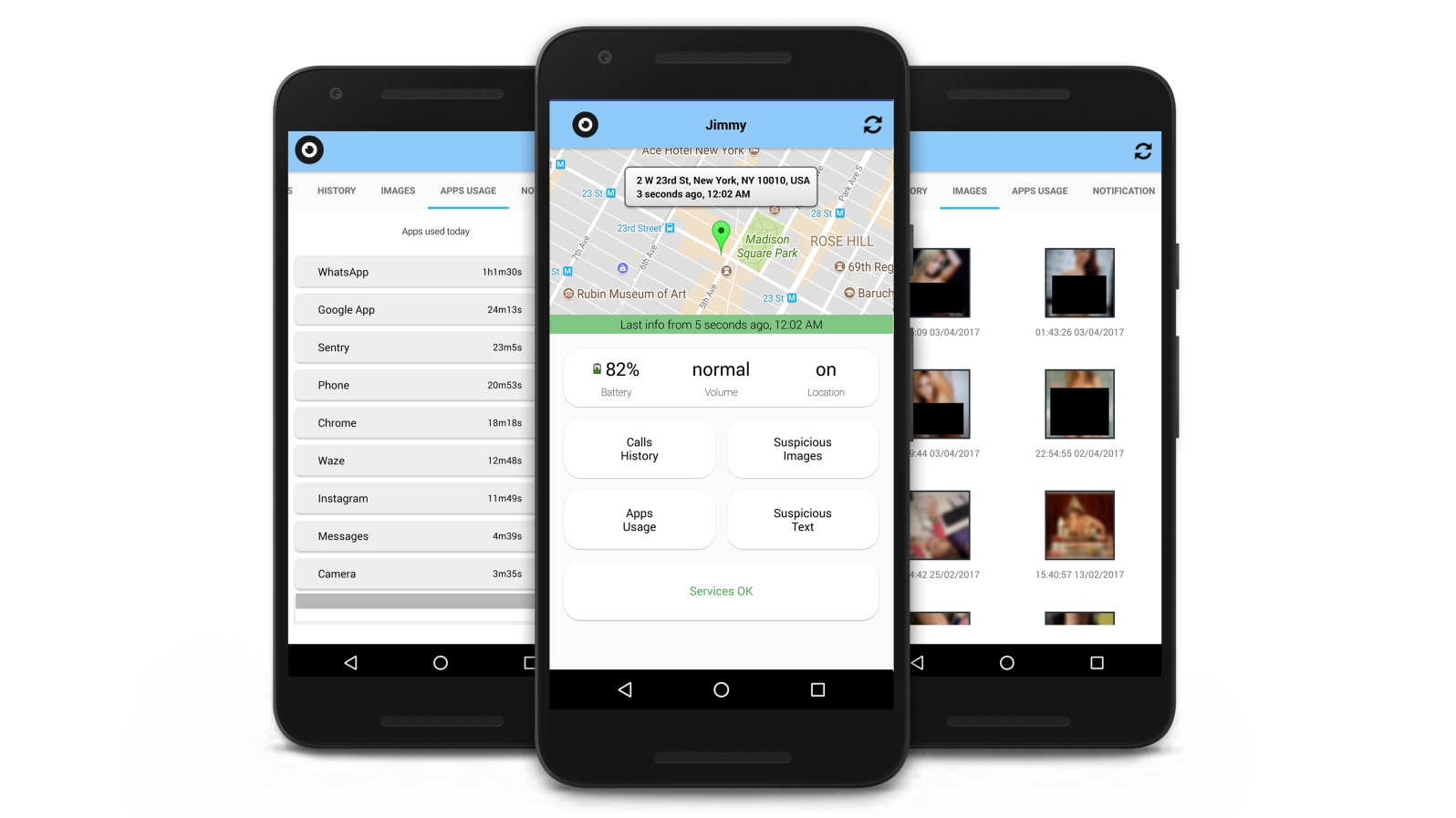

Sentry, which currently runs on Android devices, monitors text messages on all the main social networks – Facebook, WhatsApp, Kik, Instagram and Snap – as well as SMS. It can see every photo opened on the device, track which apps are opened, monitor call history and update parents on where the phone is being used based on its geolocation.

Sentry can do all that without requiring the phone’s user (the child) to share his or her passwords. That makes Sentry different than competitors like Qustodio, Bark and UKnow, which require children to provide their parents with login credentials.

“We see everything that happens on the device,” Druker tells ISRAEL21c. “If a child really wants to hide content from his or her parents, it’s easy to change the password or open another social media account. Children are very smart these days!”

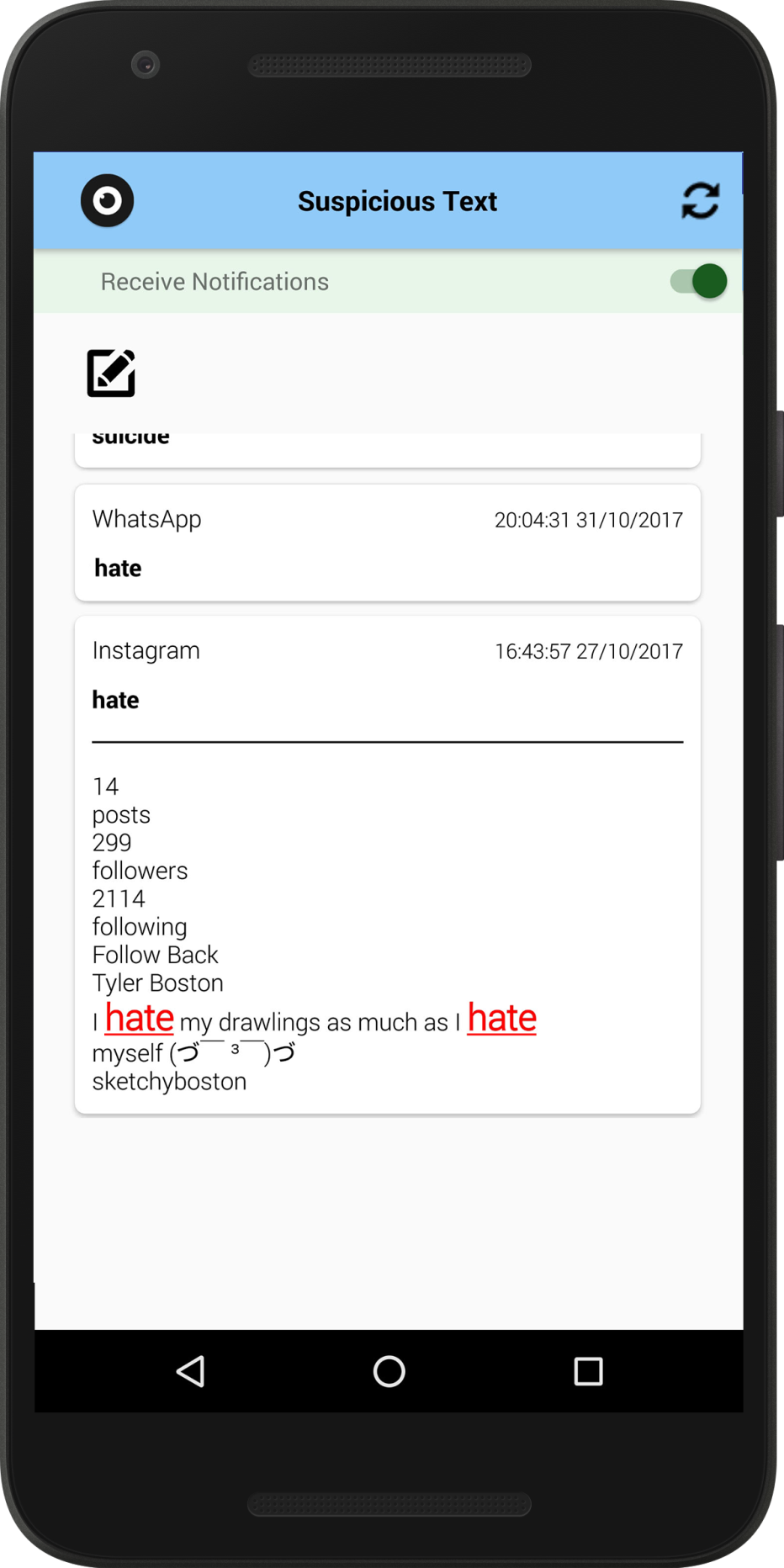

Druker used his background in image recognition to develop the algorithms Sentry deploys to detect nudity in images and to parse texts. The app works entirely through machine learning. “No human is looking at those pictures, thank God,” he says.

When Sentry finds a suspicious match, it sends an alert to the parents’ dashboard. If it’s an image, it’s “blurred and in a very small format,” Druker explains. “We realized that parents could be exposed to naked images of other children. We don’t want to be the platform that allows them to do that. The blur makes sure you can’t identify anyone in the image. We want to protect the child’s privacy as much as we can.”

It’s then up to the parent to confront the child on the content of the alert – which begs the question: Why would a child allow his or her parent to install a monitoring app?

“I use the analogy of a seatbelt,” Druker tells ISRAEL21c. “I may think I’m a decent driver. I’m not involved in many accidents, so maybe I don’t need to use a seatbelt. But I still do. It’s the same here. Children are savvier at using their smartphones than their parents. But being smart doesn’t mean they understand all the consequences of what they do and what could happen.”

Moreover, usually the parents are paying for the phone. “As a parent, I have the ‘keys,’” Druker says. “I use this as an excuse to talk about the threats of social media with my kids. We don’t block anything. We’re only notifying parents about suspicious content. It’s then up to the parent to decide how to handle it.”

Cyberbullying protection

The initial impetus for Sentry was preventing cyberbullying. Druker cites statistics showing that nearly 35 percent of children have been threatened online and many are afraid to report it. As a result, they can “become depressed. There are suicide attempts.”

The more Sentry users there are, the better the app works. So the app is free of charge until a critical mass is reached. “Later, we’ll charge a monthly subscription,” says Druker, who runs his bootstrapped company out of the Hubanana co-working space and is currently raising a seed round to develop better predictive behavior, boost marketing and develop a version for the iPhone.

The app has generated respectable organic success to date, with some 4,000 children registered. The app can support multiple users; some parents have several children monitored, Druker says. Sixty percent of users are in Israel, 18% are in the US with a sprinkling in Spain, the UK and Russia.

The parents of the 13-year-old in Arizona are full of praise for Sentry.

“A TV can’t watch your kids. A video game system cannot watch your kids. You have to do that,” the child’s father told USA Today. “If we didn’t have the app, and we didn’t take all the steps, we’d never have known this happened to my son.”