If you could see into the mind of visual artist Sigalit Landau, it might resemble her cavernous Tel Aviv studio. The industrial space unfolds into seemingly endless rooms packed with eclectic objects she’s created for exhibits across the globe, along with models of future works.

Wearing paint-splattered orange slacks, her blond hair streaked with a shock of blue, the 44-year-old artist laughs when asked how she focused her inborn talents as a young art student. “I don’t know if I’ve focused my creativity to this day!” she tells ISRAEL21c.

Indeed, Landau’s rising fame seems to be based on her brilliance in transforming a creative stream of consciousness into works of art. You can’t pin her to one genre.

Tons of treasures are stashed throughout the studio. A papier-mâché bike-rider topped with a neon sign blinking “LOVE.” An old bomb shelter she bronzed. Marble and stone sculptures. A wedding dress of Dead Sea salt.

- Sigalit Landau portrait by Eldad Karin.

The Dead Sea is the lowest point in the world, a major Israeli tourist attraction and an inspiration for international visual artists including Spencer Tunick, whose “Naked Sea” involved 1,000 nude participants.

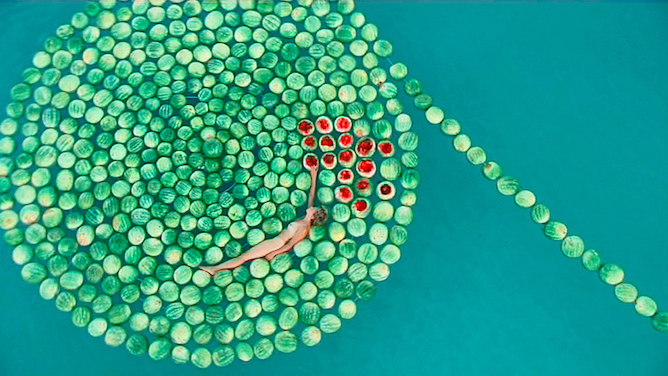

Landau shed her own clothes to create “DeadSee” at the spot in 2005. Now displayed at the Israel Museum, the 11-minute video shows her floating in a slowly unspiraling string of watermelons on the water’s surface. One of only six signed copies was sold at a Sotheby’s auction in December for $125,000.

Still to come is the Salt Route, Landau’s ambitious bridge linking the Israeli and Jordanian shores of the Dead Sea. The planned border crossing is to be paved and adorned with crystals mined from the mineral-rich sea. The target date for completion is October 2014, the 20th anniversary of the signing of a peace treaty between the two countries.

- One of Landau’s conceptions of the future Salt Route Bridge.

A wandering Jew

World War II wreaked havoc on the lives of Landau’s parents long before they married and raised a family in Jerusalem. Her mother was born in London to Viennese refugees. Her Romanian father grew up in orphanages in pre-state Israel.

“It was a bit of a mess but quite fertile for creativity,” she says. “Art was encouraged. I grew up with a lot of [Marc] Chagall.”

Sigalit was a dancer and also took classes for kids at East Jerusalem’s archeological showcase, the Rockefeller Museum.

“We learned modern art among the antiquities,” she says. “We were shoulder to shoulder with children from Arab villages who were growing up tending flocks of sheep.”

- “Holes Roles Pillars and Poles,” a 2013 work in white marble.

After completing high school at the Rubin Academy of Music & Dance, and then military service, she entered Jerusalem’s renowned Bezalel Academy of Art and Design.

“I went to Bezalel right away because I was eager to get my hands into doing,” she explains. “I didn’t go to India or South America like many others do after the army.”

Attracting international attention early in her career, Landau did get to see the world after all. She has exhibited in museums, galleries and private and public venues in Paris, Budapest, Moscow, Berlin, Madrid, Rotterdam, Venice, Tokyo, Stockholm, Sydney, New York and Toronto, among others.

“I’ve become a wandering Jew,” she jokes. “Between 1996 and 2003 I didn’t even have a base and I didn’t make a living from art. Everywhere I was invited to exhibit, that is where I lived.”

Today she is based in South Tel Aviv, living with her seven-year-old daughter, Imree, across from her rented studio. “Imree’s dad lives down the block,” she says. “It’s a very sexy neighborhood full of businesses opening and closing, woodworkers, metalworkers, music and alcohol.”

A familial crew of young artists and photographers minds the fort while she’s exhibiting abroad and collaborates with her when she’s home.

‘Four Mothers’

Landau often uses biblical references to title her works. “When you grow up in Jerusalem, the Bible is a big part of how you see everything, even if you’re secular,” she says.

“Four Mothers,” alluding to the matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, Leah and Rachel, was part of a larger exhibition devised for Berlin and installed last year at the Negev Museum of Art in Beersheva. Landau interviewed four elderly Israeli women of different ethnicities, and projected their recorded stories from the four burners of a battered oven in a set built to look like a 1950s Israeli kitchen.

“These absent women open their intimate existence to us, through the magic of their voices, and the evocative power of their recreated domestic environment,” says Landau.

- Women’s voices from the stovetop.

Negev Museum Director Dalia Manor notes that Landau developed “Four Mothers” in the time period between losing her mother and becoming a mother herself.

“Like a curious young adolescent, listening attentively to the wisdom of the older generation, Landau is absorbing and recording, inquisitively asking her questions, and reiterating specific details; paying special attention to the mother’s role, particularly when it comes to feeding and cooking. In the course of conversation, she induces her companions to recall memories of childhood and family, immigration and survival, work and pride – individual life stories that merge into the Jewish-Israel-Female narrative.”

One participant in a group tour from the Mizel Museum in Denver last year told ISRAEL21c that Landau’s work in Beersheva “touched the depth of despair that I have never experienced with an artist before in terms of a woman’s experience, the Jewish experience from generation to generation and the Holocaust experience. Standing in her exhibit, the tears just flowed.”

Landau currently has shows in Jaffa (Israel) and Florence (Italy) and will exhibit in Rome, Barcelona, Liege and Jerusalem during 2014. “Moving to Stand Still” opens February 6 at the Koffler Centre of the Arts in Toronto.

For more information, see www.sigalitlandau.com.