Eitan and Tali Frank Horwitz moved to Ashkelon a year ago after many decades in a Jerusalem suburb, trading a desert view for a sea view.

Eitan, a newly licensed tour guide in his early 60s, was eager to help people explore the area around this ancient Mediterranean port city. Tali, a social worker, wanted to contribute to the city and be part of Ashkelon’s growing English-speaking community.

Ashkelon’s population has swelled 25 percent over the past decade despite its six-mile proximity to the Gaza Strip, and the occasional “drizzle” of rockets from that Hamas-led enclave.

Early on the morning of October 7, the drizzle turned into a fierce storm as Hamas launched surprise attacks.

Since then, the city of 162,000 residents — 36,000 of them children – has counted 125 buildings completely destroyed by missiles from Gaza and many more cars, buildings and infrastructure damaged.

“A scenario like this did cross our minds,” Tali admits, speaking to ISRAEL21c from a borrowed Jerusalem apartment where she and some of her grown children are taking refuge.

“But we’re at the point in our lives where we can do something pioneering to strengthen the south. We wanted to give. Ten days before the war started, we drove to Kibbutz Be’eri, Sderot and Netivot to take pictures and buy falafel, to show support of our greater neighborhood.”

Now that neighborhood is largely evacuated in the wake of death and destruction.

At home in Ashkelon, “I could not believe the intensity of the explosions, the booms. It looked like the set of a movie with charred cars, the smell of fire, toxic fumes from Israel’s shelling of Gaza. Our supermarket was blown up. Even the national park was on fire,” says Tali, referring to the archeological park with 5,000-year-old artifacts.

“You feel the ground shaking. You could jump out of your skin when you feel the boom of David’s Sling [missile defense system]. I even heard machine-gun fire of infiltrators. I don’t watch scary movies, yet I was in the middle of one.”

Craters and shrapnel

Her husband offered to be “fixer” for foreign members of the press. Two Belgian reporters watched a barrage of incoming rockets on October 10 from the Horwitz’s high-rise apartment.

“I saw the fear on their faces, though these guys had been war correspondents in Ukraine,” she says. “Broadcasting from our porch, they looked down at people cleaning up after maybe 15 rockets fell. You could see craters and shrapnel everywhere.”

Before decamping to Jerusalem – with Eitan remaining in Ashkelon – she and a friend delivered 1,800 bottles of water to the staff of the city’s Barzilai Medical Center.

“I saw a bewildered elderly man who was alone and scared. He told me that he comes to the hospital daily to get food,” she says.

“We haven’t even started to touch the layers of trauma in this country.”

Truly heartbreaking

Shachar Zahavi, founding director of SmartAID, describes a scene from Ashkelon that he witnessed when his organization was bringing in trucks full of clothing, folding beds, hygiene products and much more, shipped by overseas donors.

“We encountered an elderly Holocaust survivor who was dependent on a foreign caregiver for her daily needs, from eating to taking medication, taking a simple shower and attending health check-ups,” Zahavi relates.

“Unfortunately, most of the foreign caregivers have fled Ashkelon and the surrounding areas, leaving hundreds of individuals without their support system. This situation is truly heartbreaking, and even though we are overwhelmed, we cannot give up; we must continue with unwavering determination.”

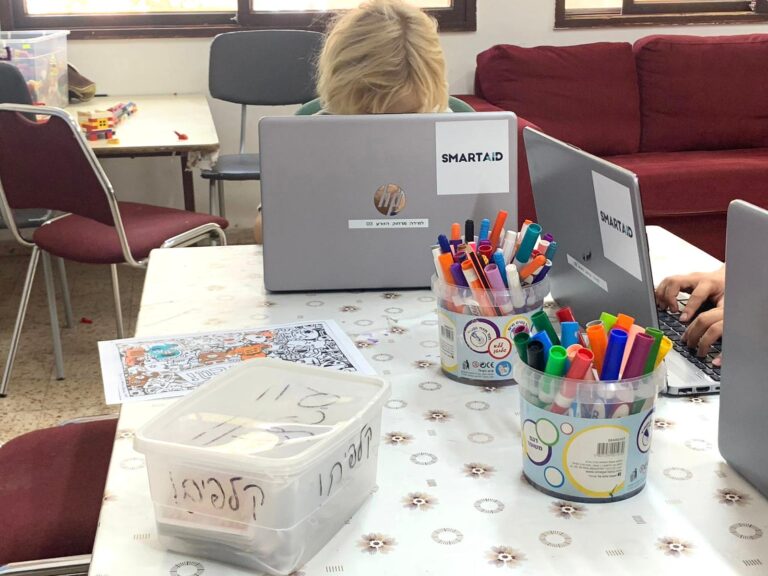

At the other end of the age spectrum, SmartAID is harnessing experience gained from its Smart Class projects in Ukraine, Moldova, Poland, Turkey, and other disaster-stricken regions to enable online learning for Israeli schoolchildren in evacuation centers and in cities like Ashkelon where schools remain closed.

Zahavi notes that more than 2,000 Ashkelon residents have been injured since the start of the war, and 40 percent of its population was evacuated due to a lack of protected shelters.

“Many more are expected to leave when the Israeli army enters Gaza, as Ashkelon is a primary target,” he says.

‘Doing the best we can’

At least for now, Deborah and Michael Zwebner are staying put in Ashkelon, their home for the past five years.

“We always brought our children to the Delila Beach in Ashkelon from our home in Beit Shemesh, and I thought for the last quarter of my life it would be nice to live near the sea,” says Deborah Zwebner.

The occasional red-alert sirens, she says, were more of a nuisance than a life-threatening concern – until October 7.

“I woke up at 6:20 and heard what couldn’t be mistaken for anything but rocket fire, but no sirens went off. Then it happened again and again. Then the sirens went off and we went to our mamad [fortified room], which we keep stocked up with canned goods, water and nonperishables,” says Zwebner.

“None of us knew of the atrocities or the level of the massacre at that point. We just wondered why they were so mad.”

One of the apartments in the Zwebners’ complex took a direct hit. The resulting concussion damaged the glass door and some windows of their building.

“We’ve had hits on cars around the corner, a blown-out taxicab down the street. Four blocks away at Marina Mall, there was a direct hit at the entrance to the parking lot and the generator. So it’s all around us,” she says.

“We’ve had offers to go to other people’s houses but I’m very frightened to be on the roads,” says Zwebner, who helped an expectant couple from Kfar Aza, on the Gaza border, find temporary lodging near a Tel Aviv hospital.

“I always make the decision to stay here. My husband and I live here and we will not be chased out of our home. We’re here, and doing the best we can in this situation.”

Heroism and humor

Tali Frank Horwitz feels guilty about fleeing Ashkelon. However, she says her decision makes her grown children and her mother feel calmer.

She’s been making videos for social media, sharing stories of heroism — and even humor – under fire. “People are responding. They want to hear individual stories,” she says.

Meanwhile, Eitan is volunteering in Ashkelon and beyond.

“His friend came from the US with more than $10,000 worth of medical supplies and they’ve been delivering it to the frontlines south and north. My daughter, who was supposed to start Ashkelon College this semester, is helping people get packages from one place to another; her phone became a coordination center.”

The danger is still acute.

“Yesterday, a dead terrorist washed up on the Ashkelon shore about a five-minute walk from my front door,” she tells ISRAEL21c. “If he ran, maybe two minutes.”