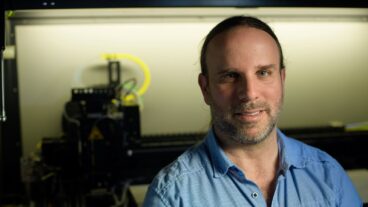

For nine months before the 7th of October, Prof. Karine Nahon, head of the Data, Government and Democracy Program at Reichman University, was leading protests against the government’s proposed judicial reform.

On October 7, the data scientist switched gears, using artificial intelligence (AI) to determine the status of thousands of people missing after the Hamas attacks on Israeli Gaza border communities.

“At 10 o’clock that morning, eight or nine of the leaders of the protests met on Zoom. We decided to create a civilian war room,” Nahon related at the recent AI Day led by the Blavatnik Interdisciplinary Cyber Research Center with the Tel Aviv University Center for AI and Data Science.

“We really didn’t know what we were talking about,” she admitted.

“We didn’t know yet that there were hostages and missing people. We thought at the time that about 30 people were dead and we wanted to help somehow, to evacuate people.”

By the afternoon, as reports of killings and kidnappings continued rising, Nahon and her committee canceled all 150 protests planned for that evening and called a meeting for 8am Sunday morning.

“Everyone took on a project. I offered to be in charge of finding missing people. After all, how many could there be? I was sure this project would just take five or six hours and I’d go home,” she said.

Former IDF chief of staff Dan Halutz and high-tech executive Ari Harel volunteered to co-lead the effort with Nahon.

Data force

The volunteers began by trying to determine how many residents, visitors and Supernova rave partygoers were actually in the affected areas that day.

Nobody could give them these numbers – not the IDF and not the Interior Ministry.

“So we said to each other, what is our force? Our force is data, information that exists with the people who were there on the ground.”

Nahon contacted all 25,000 people in her judicial protest WhatsApp groups, seeking volunteers. “The next day, we had 1,500 volunteers manning a huge war room from morning to night.”

Each of these volunteers sent out calls for photos, videos or lists from anyone who’d been in Gaza border communities on October 7.

“Two days later, we had collected 200,000 videos. It was mind-blowing,” said Nahon. Later they also received official government footage from security cameras and GoPros.

“You find yourself with vast big data. You don’t know whom you’re looking at. You can’t use regular AI tools because they work on facial recognition. How do you recognize a face from the body, when the face doesn’t exist or is covered in blood?

“You can’t go to Target and find software that looks for missing people. We had to invent our own algorithms. We had to develop tools so our volunteers could tag things and create metadata.”

Volunteers from the tech world, academia and business examined frame after frame attempting to identify people by face, voice, tattoos, jewelry, even patterns on underwear or pajamas.

They scoured TikTok, Telegram and WhatsApp, scraping any data that mentioned people in the south that day.

Hamas alone had 150 Telegram channels where terrorists were uploading videos of their massacres. “It was a struggle to get the videos before the platforms removed them,” said Nahon.

Time was ticking

“We had 15 different ‘clients’ — governmental agencies and security forces — waiting to hear from us every second,” she said.

“And time was ticking. Everyone in the war room saw a metaphorical clock before their eyes. We knew that after a week the chances of finding people alive was almost zero.”

Nahon didn’t allow them to work remotely. Every volunteer had to be present in the war room at the Expo Tel Aviv convention center for the three and a half weeks the team was deployed.

“We developed techniques and AI from voice recognition to facial recognition to body recognition to social network analysis,” says Nahon.

“But technology alone was not enough. It was not a regular lab where you have time to test and experiment. This was an event where there was zero margin for error. You can’t say you saw somebody without being 100 percent sure; a whole country was waiting to hear how many missing people are still alive and how many are dead.”

As the machine-learning technologies that pored over 200,000 videos got smarter over time, so did the people using them.

Human intelligence

“In order to identify people at a time when they looked very, very different than in their daily lives, we had to use a lot of human intelligence,” says Nahon.

For example, after seeing white Toyota trucks used by the terrorists in some of the videos, they trained the system to look for these vehicles in all the videos.

“You can’t go to Target and find software that looks for missing people.”

Volunteers skilled in graphics improved the quality of poor videos so the AI could do its job better.

“We used social network analysis with natural language processing so we could know who were the terrorists who kidnapped a particular person,” Nahon said.

“The catch is, once they get to Gaza, you don’t see the kidnapped people anymore. The terrorists who kidnapped them continue to circulate around. So we said, instead of trying to find the hostages let’s try to find the people who took the hostages and then maybe we can track down more information on the hostages.”

Ask the right questions

After three days, the war room volunteers narrowed an initial list of a possible 10,000 missing people to about 4,300 whose whereabouts remained unknown.

After three and a half weeks, they managed to determine the status of all but 50 before passing their data to government and security officials.

“AI is wonderful and allows us to solve problems that we didn’t think we could solve,” Nahon said.

“But it all comes down to creating a space where you ask the right questions. In our space, I didn’t look for one [specific] algorithm. I told everybody who had an idea to start working. We had 10,000 missing people to find in a short amount of time.”

In the event of another multi-casualty disaster, she said, “we’ll be able to create this war room again in two hours because we learned a lot.”

And although her short-lived team isn’t authorized to share the novel technologies and techniques to other countries, she is hopeful that the Israeli government would do so if a need arises.

“We basically invented at least six algorithms that did not exist before and could help in other multi-casualty events in other places in the world,” Nahon said.

On February 28, ahead of International Women’s Day, Nahon received a Peres Center for Peace and Innovation Medal of Distinction as one of 20 heroines of October 7.