The idea behind Lightricks, the Jerusalem unicorn that specializes in image-and video- editing apps, was simple: to allow people to realize any creative vision, even if they lacked the skills to do so.

“I’m not an artist; I don’t know how to paint or sing or anything, but I do see things in my mind that I’d like to show other people,” Lightricks cofounder and CEO Zeev Farbman tells ISRAEL21c.

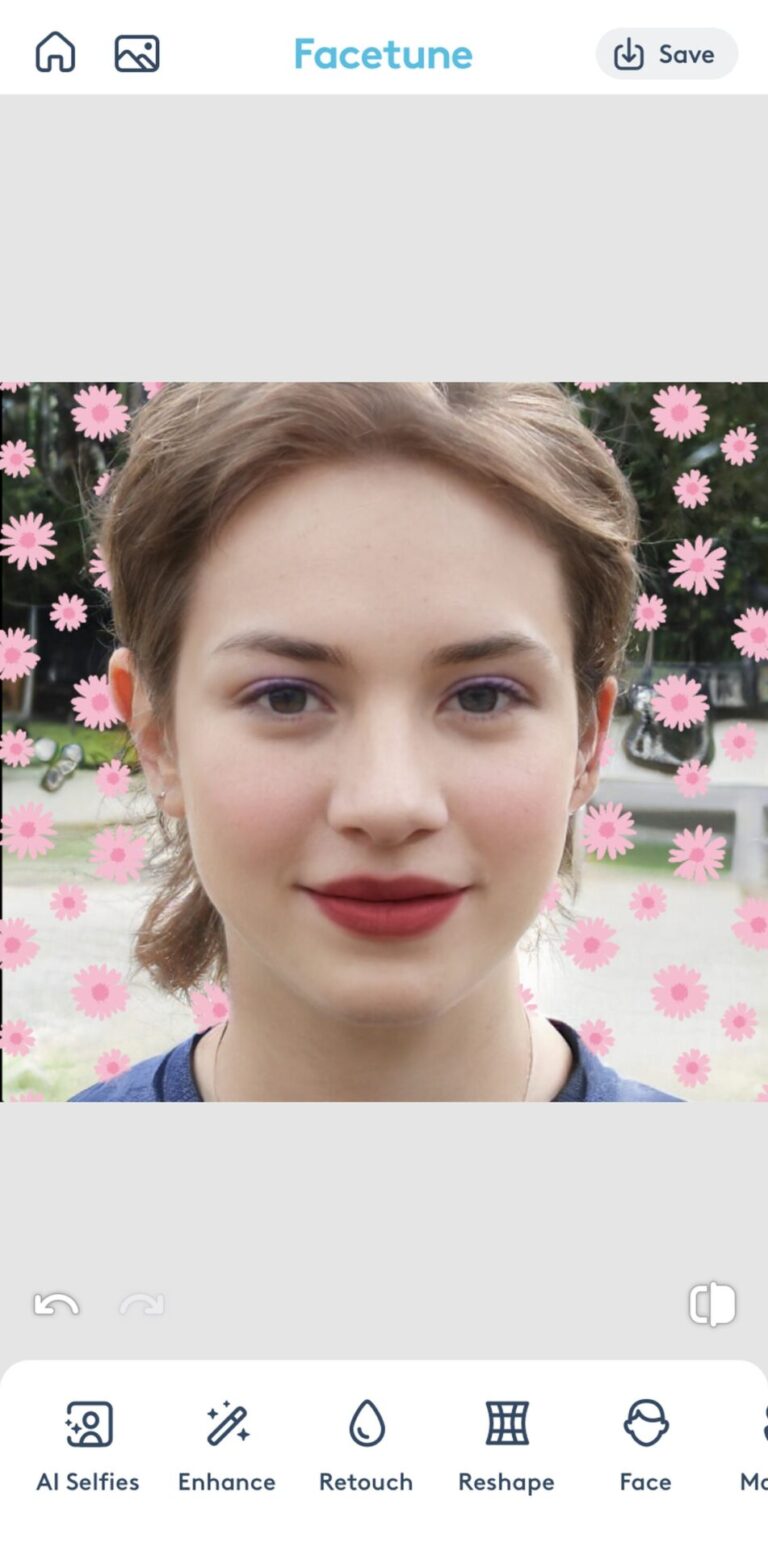

“With us, people can be creative, even if they don’t have the technical abilities for it. At first, it was simply about making apps that tackle certain verticals – for example FaceTune, which is a mobile Photoshop,” he says.

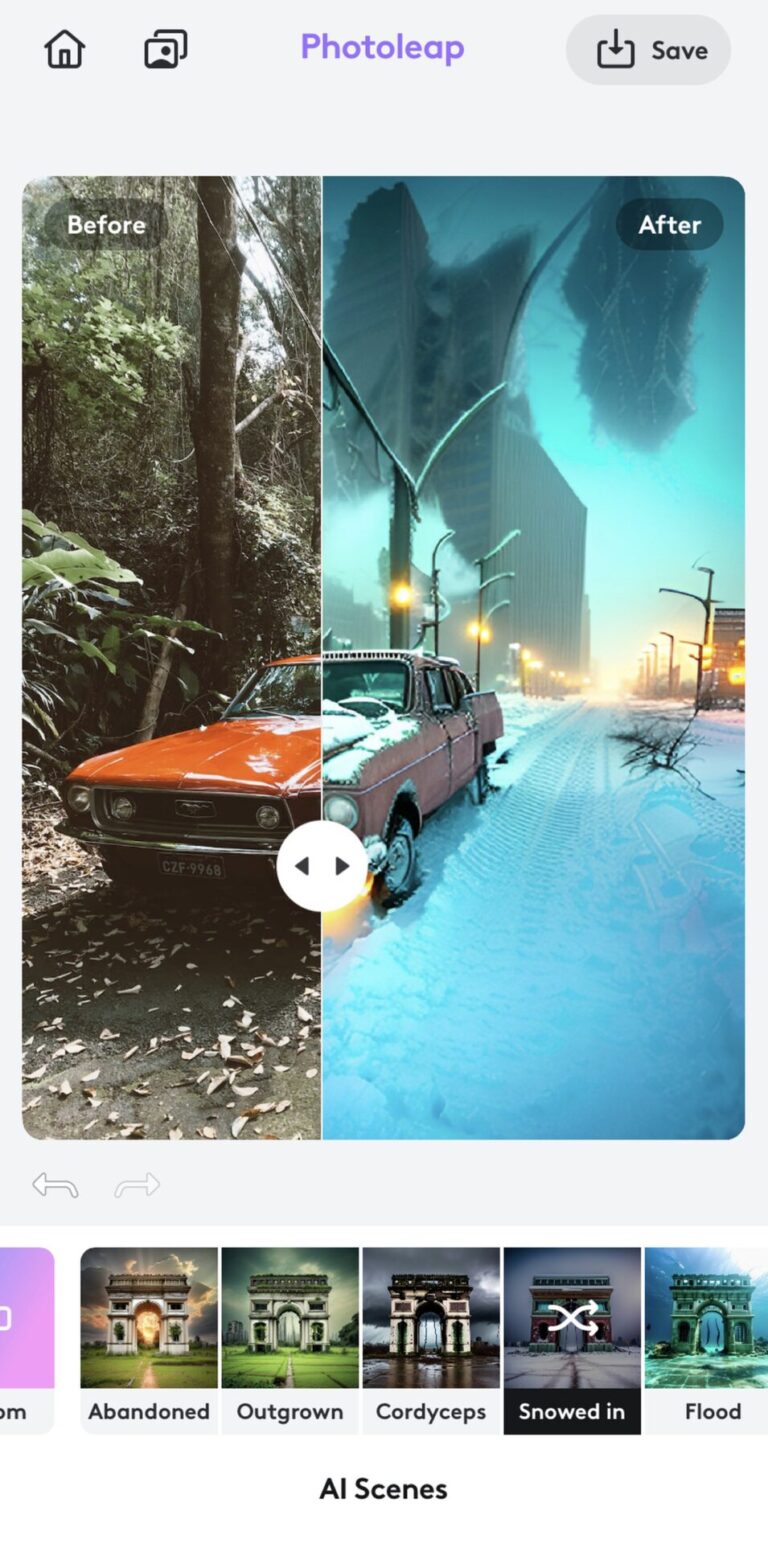

“Now, with artificial intelligence, we’re reaching a stage where we’re beginning to feel that the vision we had is becoming viable – machines can help you show others the things you’re imagining very quickly. That’s why this is going to be the most fun time ever in our industry.”

The company recently was ranked fifth in valuation by CB Insights on its list of 13 worldwide generative AI unicorns.

Lightricks was founded in 2013 by a group of army friends completing their PhDs in computer science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

They developed a slew of super-popular mobile apps for image and video editing, pre-image viewing, image animation and story-making.

Lightricks apps have been downloaded nearly 700 million times and claim more than 30 million monthly users.

The big disruption

“When we started out, our audience was people who wanted to create social media content that simply looked better,” Farbman explains. “They needed more agile tools. But as users became experts, we were able to give them deeper products with more content.”

When mobile entered the world, it was a huge revolution that disrupted many areas, Farbman reflects.

Now, however, mobile has “reached a sort of plateau regarding what each generation of devices can offer,” he says.

“Within the space of a decade, we’ve turned from an industry that had a very small place on the App Store to a huge one. The world is already looking for the next technological shift, which appears to be arriving right about now.

“This big shift is AI, and it’s disrupting all the different technological verticals, from binary digits and hardware to consumer products. AI is readily available, and anyone can disseminate it,” Farbman notes.

Changing the rules

Lightricks saw two options regarding this new technology that’s changing the rules of the game.

“One option is to run ahead with it very quickly and try and understand the advantages of this new game, and the other is to go out of the game. We’ve decided to stay in the game,” says Farbman.

“We’ve decided to incorporate AI tools in our products, and we’re also doing a lot of internal work across the company to use AI to be more productive. And while it’s very difficult to create change inside an organization numbering 10,000 people, with 600 people it’s a lot easier.”

Most Lightricks employees are in Jerusalem, with more in Beersheva, Haifa, Chicago and London.

Its Jerusalem headquarters is on the leafy Givat Ram campus of Hebrew University, and this close connection to academia continues to influence the company’s character.

“We recruit a lot from the university and the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. Our [former PhD] supervisors are just around the corner, and we’re in close touch with students,” he adds.

A changing business model

Asked about the challenges faced along the way, the now-bald Farbman jokes that a decade ago he had a full head of long, black hair.

But really, the biggest challenge was having to reevaluate the business model several times.

Over the course of the decade, Lightricks went from a standard paid apps model to a then-innovative freemium subscription one. Now it’s occupying a niche in the AI and creator economy.

“You can suddenly compete in any field, because the technology’s nature doesn’t limit you to one kind of platform, and this is accompanied by very large challenges,” Farbman says, acknowledging some internal friction. Last summer, about 70 Lightricks employees in Israel were laid off.

Looking forward, however, Farbman envisages a future of untold AI possibilities.

“At the moment, we’re experiencing technology that bridges the gap between natural language and computer language,” he explains.

“You’re already used to the computer doing something for you, for example a calendar app. If you have a certain task, you search for a product to help you. But an already imaginable situation is one where you work with an agent that not only knows what you want to do, but also builds you an interface on demand.”

While this concept of automating tasks can be envisioned now, “we don’t yet really understand its boundaries because the wiring is still missing – all these systems don’t know how to wire to one another yet,” Farbman explains.

“But I think it’s better to be optimistic rather than pessimistic about all this. Otherwise it’s difficult to sleep at night.”