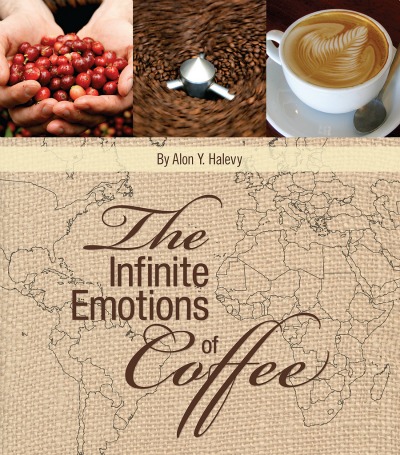

Israel gets the fattest chapter in Alon Halevy’s The Infinite Emotions of Coffee, a book examining the link between culture and coffee in 30 countries on six continents. And not just because Halevy was born and bred in Rehovot, one of the oldest cities in the Jewish state.

“What I found interesting about Israel is that I could traverse the entire history of coffee in a short amount of time,” he tells ISRAEL21c in a Skype conversation from his office at Google Research in Mountain View, California.

He explains that coffee was first discovered in Ethiopia, and spread to the Ottoman Empire through Yemen. The Turks introduced it to Europe.

“In Israel, I was able to go to an Ethiopian grocery in Rehovot that sells bags of green, unroasted beans, and then to a Yemenite friend of my parents who showed me how they prepare coffee with spices. In Jerusalem’s Old City and in Jaffa you’re seeing Turkish coffee traditions at their best, and then in Tel Aviv you see the latest in Italian espresso drinks.”

Halevy’s coffee wanderlust comes courtesy of frequent business trips as head of the team that builds Google fusion tables, a practical tool that makes structured data more widely available and usable.

“I travel a lot for my job, and the first thing I explore is nice cafés. I noticed I was getting very different experiences in the places I’d been to in a pretty short span of time — New Zealand, Prague, Zurich, Israel, Vietnam. I wondered about the relationship between culture and coffee, and started investigating. Before I knew it, I was writing a book.”

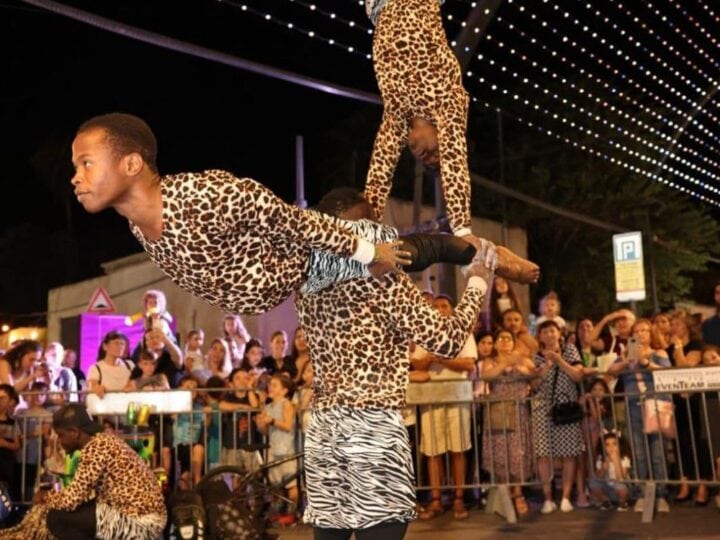

Self-published in December, The Infinite Emotions of Coffee has 180 photos among its 159 pages. Halevy’s wife, Oriana, edited the work. “Her English is richer and more correct than mine,” he says humbly.

Charting his own course

Born in Israel in 1963, Halevy left at age 25 to earn his doctorate at California’s Stanford University. His unaccented English is due to his mother, an ex-New Yorker who spoke her mother tongue to her two children.

Because his father was a professor of chemistry at Rehovot’s prestigious Weizmann Institute of Science, young Alon had entrée to the nascent world of computers. He took a programming course for youth there and “wrote a bunch of programs for fun,” including one to manage the budget for his father’s department.

“I remember one day the guy in charge of the computer center saw me, a 15-year-old at a terminal, and told me to get the heck out of there. My father intervened and I got my seat back, but when I started doing computer programming I had to chart my own course, read documentation clearly not written for people my age, and learn through trial and error.”

When he saw his mother, a music teacher, tediously transposing scores for different instruments, he figured that a computer should be able to automate the task.

“I spent a year and a half during high school working on that program and got an award from the Weizmann as part of an annual competition that people all over country participated in.” He even convinced his high school to count the project toward his matriculation exams.

While earning his bachelor’s in computer science and mathematics at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, he had a side job writing software for the Weizmann.

Macchiatone maven

After Stanford, Halevy worked at AT&T Bell Labs in New Jersey, then taught computer science at the University of Washington, where he founded the CSE Database Group in 1998.

His expertise in artificial intelligence and data management led him to start two high-tech companies, Nimble Technology and Transformic. Google acquired Transformic — and its founder — in 2005.

Married since 2000, the Halevys have two children. Karina, 10, and Kasper, six, both show an interest in Dad’s coffee hobby.

“Kasper likes to help me roast the beans, and Karina has spent time with me watching international barista competitions on the web,” Halevy reports.

The Israeli entries on his website’s list of recommended cafés include Arcaffe – mostly because the chain serves his favorite concoction, macchiatone (“basically a cappuccino, but with less milk”) — as well as Tamar, Sucar and Tolaat Sfarim cafés in Tel Aviv; Café Capiot in Haifa; and Puah in the Jaffa flea market.

“It’s not a systematic study; it’s just places I went to and thought worthy of mentioning,” he stresses. Some were suggested by one of his interviewees, Tel Aviv University economics professor Ariel Rubinstein, an Israel Prize winner who “conducts all of his business at cafés.”

Halevy says his ingrained Israeli can-do attitude made him confident that “there is a way of doing anything you think is worth doing — it just takes creativity. That’s been my guiding principle in terms of entrepreneurship and in the way I conduct myself. I went to 30 countries and wrote about coffee even though I’m not a coffee expert, and now I have many friends in the coffee world.”