A groundbreaking interdisciplinary study by Tel Aviv University (TAU) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU) involving 20 international scientists and researchers has verified biblical accounts of the Egyptian, Aramean, Assyrian and Babylonian military campaigns against the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

The study reconstructed changes in the magnetic field of the earth as recorded in 21 destruction layers in 17 archeological sites throughout Israel, constructing a variation curve of field intensity over time that can be used as a scientific dating tool.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the study is based on the doctoral thesis of Yoav Vaknin, and supervised by Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef and Prof. Oded Lipschits of TAU’s Institute of Archaeology, and Prof. Ron Shaar of HU’s Institute of Earth Sciences.

Vaknin explained that Earth’s magnetic field comes from the movement of iron in its interior. When this iron moves around, it will always point north because of this field.

Archeological finds such as mud bricks and pottery vessels contain ferromagnetic minerals with tiny magnetic signals. If these artifacts are burned at high temperatures, when they cool down they record the magnetic signal that points to the magnetic north of the time.

“And we can come along thousands of years later and reconstruct the direction and the intensity of the magnetic field at the time of the fire,” said Vaknin.

Over the past decade, researchers have reconstructed magnetic fields recorded by hundreds of archaeological items, said geophysicist Shaar.

Thus the researchers involved in the study were able to cross-check the magnetic field recorded by these destruction layers with the magnetic fields of archeological items that had been dated.

“Based on the similarity or difference in intensity and direction of the magnetic field, we can either corroborate or disprove hypotheses claiming that specific sites were burned during the same military campaign,” said Vaknin.

In a previous study in 2020, researchers reconstructed the magnetic field as it was on the ninth of the Hebrew month Av, 586 BCE, the date of the destruction of Jerusalem and the First Temple by Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar.

Now, using archeological findings unearthed over several decades alongside historical information from ancient inscriptions and biblical accounts, the researchers were able to reconstruct the magnetic fields recorded in destruction layers studied, and use the data to develop a reliable new scientific tool for archeological dating.

“By combining precise historical information with advanced, comprehensive archeological research, we were able to base the magnetic method on reliably anchored chronology,” said Lipschits.

End of Judean kingdom

One of the most interesting findings revealed by the new dating method has to do with the end of the kingdom of Judah.

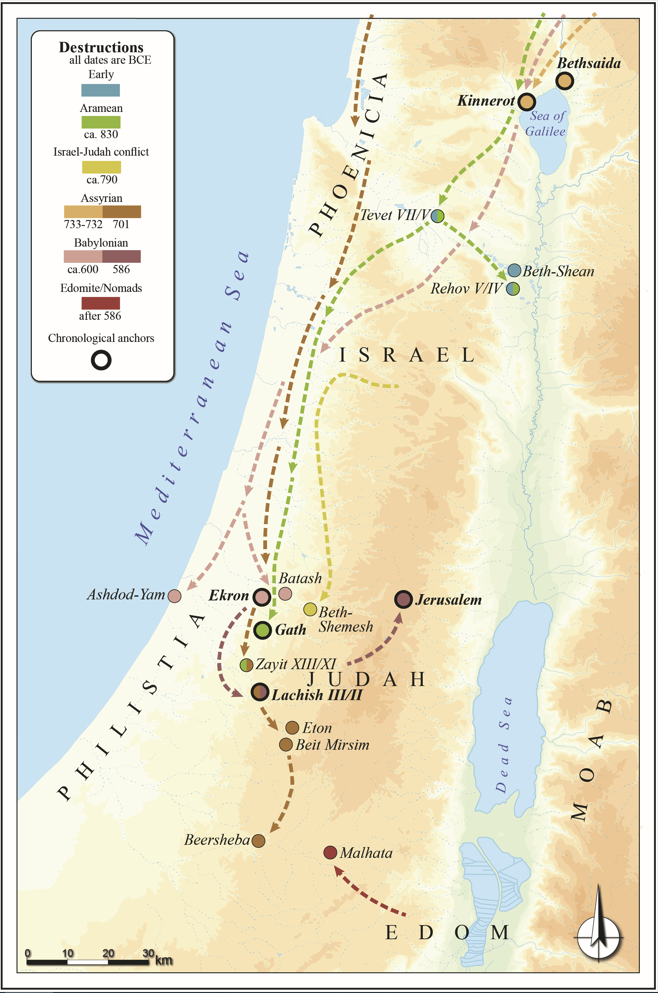

An archeologically supported hypothesis suggested that the Babylonians had wiped out Jerusalem and frontier cities in the Judean foothills, but left towns in the Negev and the southern Judean mountains almost untouched.

Recent geomagnetic findings confirm that the cities in the Negev were destroyed several decades later, probably by the Edomites, said Ben-Yosef.

“This betrayal and participation in the destruction of the surviving cities may explain why the Hebrew Bible expresses so much hatred for the Edomites – for example, in the prophecy of Obadiah,” he said.

Additionally, the identification of full statistical synchronization between the magnetic fields recorded at the Philistine city of Gath (when King Hazael of Aram-Damascus destroyed it around 830 BCE as reported in the Hebrew Bible) and those of Tel Rehov, Tel Zayit and Horvat Tevet makes a strong case that their attacks were part of the same campaign.

A different magnetic field at Tel Beit-She’an, however, refutes a previous, non-biblical hypothesis that it was also destroyed by Hazael.

Magnetic data from Beit-She’an indicate that this city, along with two other sites in northern Israel, was probably destroyed 70 to 100 years earlier. This could correspond with the military campaign of the Egyptian Pharaoh Shoshenq, described both in the Hebrew Bible and in an inscription on a wall of the Temple of Amun in Karnak, Egypt.