After 30 years spent servicing Israel’s military aircraft, engineer Hugo Tour decided to redesign a car’s internal combustion engine to make it twice as efficient.

Hugo Tour spent more than 30 years servicing Israel’s high profile military aircraft and helicopters – and advising the US Air Force, too – about what went wrong when military aircraft failed.

All that time spent in the Israel Air Force (IAF) servicing jet engines and aircraft got Tour to thinking: If jet engines, air conditioners and water heaters can achieve high rates of efficiency – above 80 percent – then why not a car’s internal combustion engine, which has an extremely low efficiency rating, at 20-30%?

Low efficiency means wasted fuel. And wasted fuel both costs money and releases polluting emissions into the atmosphere. Tour knew engines and he knew that something had to be done: “I was trained throughout my service to repair and understand machines and I became very good with machines, much better than with people,” sixty-six-year-old Tour tells ISRAEL21c.

With a formal education in political science, Tour started out as a simple technician servicing aircraft engines in the IAF. He worked his way through the ranks until by the end of his military career he was responsible for all the aircraft at Israel’s biggest air force base.

Follwing his retirement from the IAF in 1988 as a Lieutenant Colonel, and between jobs at two US companies, Tour started work on his own idea, the Tour Engine. “After I retired, I wondered ‘what am I going to do with myself?’ ” he tells ISRAEL21c.

Blowing hot and cold

He said to himself: “You know how to repair machines, so why not repair the internal combustion engine? We all know it is not the most efficient machine the world.”

Tour started out by building a combustion engine based on the design of a jet engine. He worked on it for seven years, but when he couldn’t make the engine fit his theory he scrapped his initial plan. Tour says he realized that it all comes down to separating the hot and cold processes of combustion.

“What I did is, I thought about a theory that should perform better than what we have,” he says. “I tried to build a rotary engine and make it fit to do the job of an engine. I spent seven years on it and wasted time on my theory.”

Around 1997, Tour abandoned the idea and went to work for the established US company Sargent Fletcher for a year, where he helped it to pass qualifications tests for its fuel tanks.

But his passion for creating a new engine remained. “It was with me all the time. I felt I had the answer – the question was how to make it practical,” he says.

A stroke of genius

Four hundred thousand dollars (one-third of Tour’s personal pension fund) has been invested in answering that question and building the proof of concept Tour Engine.

Once a week, he fires up the engine to see how it’s working, and with the help of his son Oded Tour in San Diego and a third party, Tour is now looking to turn his new engine into a viable commercial product.

Tour says that his son Oded, unlike Tour himself, is “not a dreamer. Oded is a practical guy who conceives everything very quickly.” In addition to Oded, Tour and his wife, who live in Kiryat Gat, south of Tel Aviv, have another son and a daughter.

“Any mechanical process has to do with hot energy and a cold environment. An engine process is involved with cold and hot sections,” Tour explains.

“You take in regular air, you compress it, it gets hotter, and some of the energy goes into the air, then you combust it with fuel and it gets very, very hot. Then you have to expel what’s left through the exhaust. Intake, compression, explosion and exhaust are all taking place in the same chamber. Here we have a conflict. We want intake and compression to be as cool as possible and then it will take less work to compress the air.

“After five years in LA I kept wondering why not take the familiar piston engine and adapt my thoughts on the same mechanism and build it a little differently: Using one piston to perform cold strokes and a second one to perform the hot strokes in order to optimize the cold side and optimize the hot side,” he says.

Double the efficiency of today’s engines

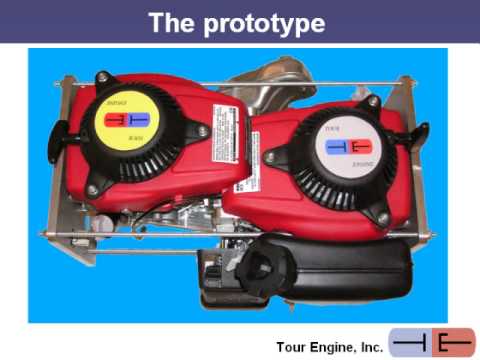

Tour took two off-the-shelf motors and fused them together, to create a split-cycle engine that separates four strokes between two cylinders. There is intake and compression on the left side – these are the cold strokes – and combustion and exhaust – the hot strokes – on the right.

Tests in US laboratories show that the Tour Engine can achieve efficiency levels of about 65%. “In real life terms, the efficiency will probably be less, but we still believe it will be twice as efficient as today’s internal combustion engine,” Tour asserts.

Backed by scientists at the University of California, Irvine, and San Diego State University, Tour is currently applying for a US government grant to advance the engine, with the help of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

“We were surprised to find almost everything I had thought of was already invented in the 1920s, but going into details we found that what was invented can’t work efficiently,” says Tour. “They were missing a few elements.”

Tour is now looking for a $1 million investment to build a state of the art prototype from scratch. It will be a long journey trying to change the system – and the basis of the modern combustion engine – but Tour’s own engines are roaring and he’s ready for the challenge.