About 12 years ago, Sha’anan Streett of the Israeli band Hadag Nahash saw teens sneaking into a concert via the restroom window, and realized that they couldn’t afford to buy a ticket.

“He felt people should be able to get culture without breaking in,” says music producer Carmi Wurtman, a longtime friend of Streett. “Culture is a basic necessity, like bread or milk, and should be available in one’s own community for a reasonable price.”

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

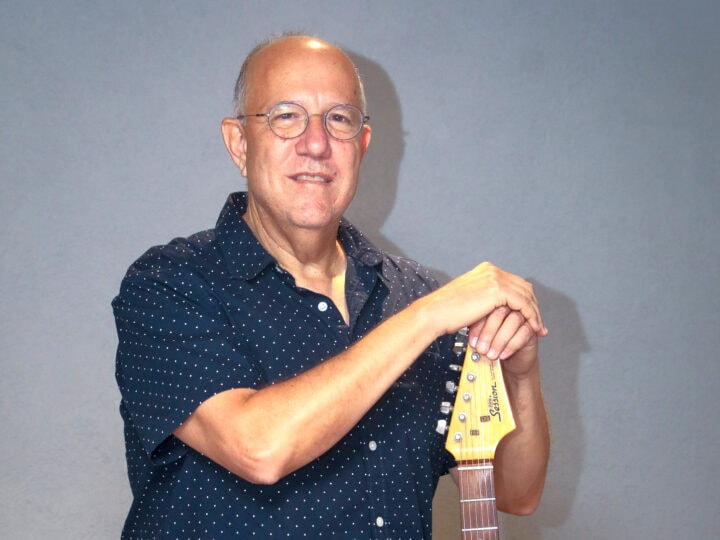

Wurtman mused that if they could find one or two major artists willing to perform gratis, they could produce a singularly affordable show. And that’s how they and a couple of friends launched Festival BaShekel — top-name summer music festivals with a ticket price of one shekel (about 25 cents) in underprivileged areas of Israel.

Why charge at all? “To give people the idea that there is value to this festival,” Wurtman tells ISRAEL21c. “We don’t believe culture should be free, just available.”

The first Festival BaShekel in 2001, headlined by rock musician Barry Sacharof and Hadag Nahash, played in Jerusalem’s Katamonim neighborhood, the Gaza border town of Sderot and the Lebanese border town of Kiryat Shmona.

Since then, hundreds of thousands of young Israelis from marginalized communities have enjoyed live performances they otherwise could not afford. As many as 10,000 attend each show, and virtually every well-known music act in Israel has participated at least once, representing a wide range of genres.

“Almost every year we go to three different places, and some we’ve repeated,” says Wurtman, head of 2bVibes Productions. Hadag Nahash still participates despite a packed concert schedule in Israel and abroad.

A musical booster for poor communities

To produce a one-shekel music festival that actually costs somewhere between 100 and 200 shekels per head, the friends established a nonprofit to solicit funds. Each host municipality contributes the performance space and ancillary services. Sound and lighting companies work at cost. The rest of the budget comes mainly from government agencies and private foundations.

“We don’t want it to be a festival of big companies, with corporate logos all over the place,” says Wurtman. The concept has gained enough grassroots support to start paying the artists “a nice honorarium.”

In the last few years, the festival founders added a young leadership piece.

“We work with kids in the local communities for about six months before the festival, teaching them to do publicity and fundraising locally,” says Wurtman. “They produce a small event of their own — a local battle of the bands. We hope to create a generation of young leaders who want to stay and help their communities.”

The winner of the competition gets three sessions with a music producer in preparation for the main festival.

“Many times we feel in these poor cities there is desperation and disbelief,” Wurtman explains. While well-meaning relief organizations are not always able to follow through on their promises, Festival BaShekel will go on no matter what. Even in Sderot, where missiles from Gaza can come crashing down at any moment, Festival BaShekel simply created an indoor version of the event.

It’s not just for teens. “Before the music, we always have activities for children and families, such as street theater,” says Wurtman.

The festival thus becomes a daylong happening that draws moms with strollers in the morning, families later in the day, and teens at night. Local businesses sell refreshments at rent-free stands.

‘A thrilling experience’

Wurtman and Streett, along with Festival BaShekel General Manager Ido Meridor and Director of Resource Development Boaz Blankistain, bring their own families to the concerts, which takes them the length and breadth of Israel.

The festival has been staged in cities including Yerucham, Dimona, Kiryat Gat, Kiryat Malachi, Sderot and Arad in the south; Beit Shemesh, Bat Yam, Lod and Jerusalem in the center; and Acre (Acco), Ma’alot, Yokneam, Pardes Hana, Mishmar HaEmek and Gilboa in the north.

“It provides a good way to see the country while putting a smile on people’s faces,” says Wurtman, who in 2008 produced a three-day Arab-Jewish coexistence festival in Gilboa with legendary rocker Joe Cocker.

The following year, Festival BaShekel produced its first Jewish-Arab festival in Gilboa.

“It has been a thrilling experience to see cultural Jewish-Arab cooperation come to life for the first time in these communities,” says Wurtman. Working with a regional organization that brings performance artists to Israel from Palestinian-administered territories as well as Jordan, Egypt and Turkey, Festival BaShekel last year booked a Ramallah-based band to play in Ma’alot.

“It was amazing to see the band drive in from Ramallah on a big bus and get on stage without incident, and to hear everyone clapping their hands at the end. Music kind of breaks through politics and borders between people.”