Ethiopian-born Tal Checol came to Israel at age 12. His schooling was spotty, and when he finished the army in 2002, college didn’t seem likely. However, that September he was accepted into the first class of a program for Ethiopian-Israeli students at Ono Academic College in Kiryat Ono, a Tel Aviv suburb.

Now 34, Checol is a lawyer in private practice. “They let me achieve my dream, and gave me the money I needed to do it,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

Thanks to visionary college programs like this, Checol is among hundreds of Ethiopian-Israelis setting a new standard in a community of some 130,000 that began arriving in Israel in 1984 from a simple agrarian society. The community still experiences high poverty, dropout and unemployment rates, but innovative higher education opportunities are making significant inroads.

Jerusalem College of Technology

The first program for this population began in 1998 at the Jerusalem College of Technology (JCT), where students complete dual academic and Judaic courses of study.

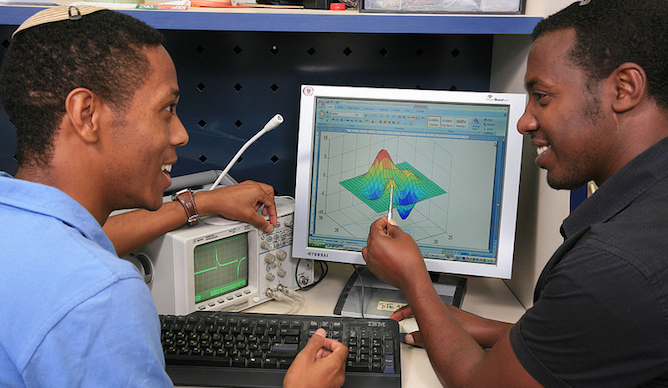

“Education for Ethiopians” prepares participants for careers in fields such as engineering, computer science, biotech and nursing on JCT’s separate campuses for men and women.

Stuart Hershkowitz, senior adviser to the JCT president, tells ISRAEL21c that 64 women and 74 men are currently enrolled, and mainstreamed into the general student body. About 90 percent must first complete a year-long prep course.

With the help of several foundations, the Jewish Agency and the government, JCT provides them free tuition and board, free tutoring, bus fare to go home on weekends (few live in Jerusalem) and twice monthly get-togethers. A dedicated counselor, Adi Yones, helps them navigate the unfamiliar academic and social landscape.

“Adi is a graduate of the program’s first years and is like a big brother to the students,” says Hershkowitz. “As a result, we have an extremely low dropout rate. And our graduates have a 100% placement record in their chosen professions, which is unusual. They’re very serious students.”

A large percentage of the men in the program have also been selected for Atuda, the Israel Defense Forces’ Academic Reserve, which allows them to complete their degree prior to active service utilizing the skills gained in college.

“This has nothing to do with affirmative action,” Hershkowitz stresses. “There are no breaks for Ethiopians at all. They have to earn Atuda like anyone else, and that is amazing since most are coming from a non-academic family background.”

Yones tells ISRAEL21c that many of the men and women he counsels were raised in great hardship, yet they excel when given proper support. “The program has changed a lot of lives,” he says.

One young man tried five times to get into Atuda and was finally successful after taking the JCT prep course. He ended up switching from computer science to a more demanding major in engineering. Others have found their niche in aerodynamics, physics or electro-optics.

“Even students with a lot of potential cannot do well if they have the worries of putting food on the table,” Yones says. “The financial, social and academic support makes all the difference.”

Ono Academic College

In early 2002, Jewish Agency community action pioneer Yigal Dunitz asked Ono founder Ranan Hartman to accept one Ethiopian-Israeli student each in its law and business tracks. Dunitz noted that only a handful of Ethiopian-Israelis were in law, accounting and banking.

Hartman told Dunitz to send 50, and a pilot program was born at the commuter school. Two of the earliest graduates are members of Knesset Shlomo Molla and Pnina Tamano-Shata.

Now the Ethiopian-Israeli program averages 150 students per year, some of them in MBA graduate studies.

Attorney Zeev Kasso, head of the program from the start, was one of the few Ethiopian-Israeli graduates of Ono before the program was implemented. He has developed a network of employers willing to provide internships to the students in law, accounting and finance.

“The students are mainstreamed in all the courses of study, and we also have unique courses to give them additional skills to succeed in the job market,” Kasso tells ISRAEL21c. “We assume success from the beginning; we have a no-dropout policy, so if you need individual support you’ll get it, and it doesn’t stop at the end of your studies.”

Doron Haran, vice chairman of resource development, says that Ono depends on domestic and foreign funding to cover most of the NIS 30,000 tuition. On top of the financial challenges of the Ethiopian-Israeli students, many also lack a family culture of academics and the all-important connections (“protekzia”) that smooth the path of career advancement.

“We are their protekzia,” Haran tells ISRAEL21c. “We must open doors for each and every graduate.”

Jewish and non-Jewish groups from abroad often come by to see the program in action, and invite students to tell their stories. It’s not unusual for someone to relate that he was a barefoot shepherd till age 12, and now is a successful lawyer at age 30, says Haran.

Yafa Marsha’s story is not quite that dramatic. Now interning in the state prosecutor’s office, she tells ISRAEL21c that although she is the first in her family to go to college, her parents always stressed education.

“Higher education is necessary for me and my community in order to feel at home in Israel and reach key positions in society and influence others positively,” says the 27-year-old Ono graduate, who hopes her younger sister will become a doctor.

Two other institutions with special tracks for this population are Kibbutzim College, which offers an Ethiopian-Israeli Teacher & Kindergarten Teacher Training Program and Yezreel Valley College, which offers an Ethiopian Nursing Program.