Barley grains from the Chalcolithic period 6,000 years ago have become the oldest plant genome ever to be sequenced, announced a team of Israeli and international researchers in the journal Nature Genetics.

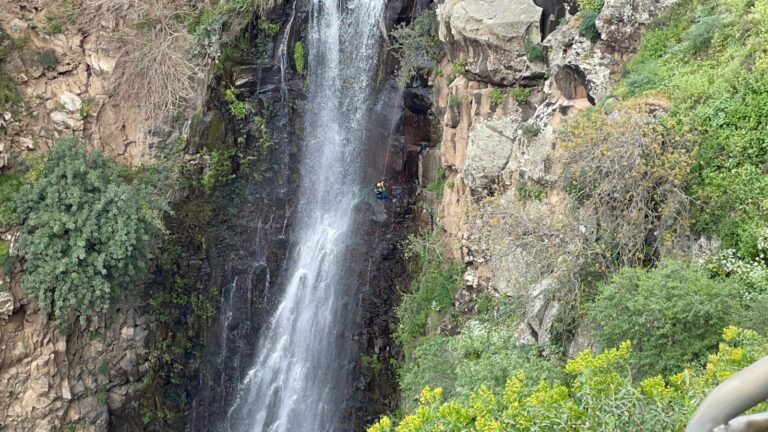

The barley grains and tens of thousands of other plant remains were retrieved from the remote Yoram Cave near one of Israel’s most popular heritage sites, the famous Masada fortress overlooking the Dead Sea.

The painstaking excavation process was headed by Uri Davidovich from the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem; and Nimrod Marom from the Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa. Ehud Weiss of Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan led the archaeobotanical analysis.

“These archaeological remains provided a unique opportunity for us to finally sequence a Chalcolithic plant genome. The genetic material has been well-preserved for several millennia due to the extreme dryness of the region,” explained Weiss.

In order to determine the age of the ancient seeds, the researchers split the grains and subjected half of them to radiocarbon dating while the other half was used for DNA extraction.

“For us, ancient DNA works like a time capsule that allows us to travel back in history and look into the domestication of crop plants at distinct time points in the past,” said Johannes Krause, director of the department of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany.

Most examination of archaeobotanical findings has been limited to the comparison of ancient and modern specimens based on their form and structure. Studying plants on the genomic level reveals many more details. Until now, only prehistoric corn has been genetically reconstructed.

It is known that wheat and barley were already grown 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, a sickle-shaped region stretching from present-day Iraq and Iran through Turkey and Syria into Lebanon, Jordan and Israel.

“It was from there that grain farming originated and later spread to Europe, Asia and North Africa,” said Tzion Fahima of the University of Haifa, where modern wild forms of these two crops are studied at the Institute of Evolution.

Nils Stein, who directed the comparison of the ancient genome with modern genomes at the Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research in Gatersleben, Germany, said the Chalcolithic seeds greatly differ genetically from the wild forms found today in the same region.

“However, they show considerable genetic overlap with present-day domesticated lines from the region,” he said. “This demonstrates that the domestication of barley in the Fertile Crescent was already well advanced very early.”

“This similarity is an amazing finding considering to what extent the climate, but also the local flora and fauna, as well as the agricultural methods, have changed over this long period of time,” said lead author Martin Mascher from the Leibniz Institute.

Comparing ancient seeds with wild forms from the region and with local barley lines grown by farmers in the Near East enabled Fahima and his colleagues at the University of Haifa and Tel-Hai College to hypothesize that domestication of barley began in the Upper Jordan Valley, far to the north of the Judean Desert’s Yoram Cave.

The researchers assume that conquerors and immigrants coming to the region did not bring their own crop seeds from their former homelands, but instead continued cultivating the locally adapted strains.

“This is just the beginning of a new and exciting line of research,” predicted second lead author Verena Schuenemann from Tuebingen University in Germany. “DNA-analysis of archaeological remains of prehistoric plants will provide us with novel insights into the origin, domestication and spread of crop plants.”

Other members of the research team were from the James Hutton Institute, UK; University of California, Santa Cruz, US; and University of Minnesota St. Paul, US.