In the 21st century, says Scopio Labs CEO Itai Hayut, there’s no reason for a lab technician to be analyzing blood samples manually under a microscope.

“It’s tedious and hard to perform consistently,” he says. “Yet it hasn’t changed much since the 1970s.”

What should they be doing instead? Let artificial intelligence do the heavy lifting, Hayut tells ISRAEL21c.

To get to that point, Hayut needed to build his own machine – a high-speed scanner that digitizes the blood-smeared slides so that a computer can do the analysis.

Scopio’s X100 Full Field PBS (for “peripheral blood smear”) can scan 15 slides an hour. A more powerful machine, the X100HT, can handle 40 slides an hour.

Both devices have received US FDA 510(k) clearance and the company is now selling its hardware to hospitals and clinics around the world.

Already, every peripheral blood smears at Tel Aviv Sourasky (Ichilov) Medical Center is done on Scopio devices, Hayut tells ISRAEL21c.

100x magnification

Scopio’s devices can scan large areas of samples at 100x magnification, while with traditional microscopes “there’s a trade-off between field of view and resolution. If you go to a very high resolution, you see a very small part of your sample,” says Hayut.

By including “the entire clinically relevant area of the sample,” Hayut says, technicians get the digital raw data and never have to go back to the microscope.

Going digital also enables tele-hematology, where a technician or doctor not physically present in the lab – or even in the same geography – can work with the data.

This is already happening with remote analysis of radiological scans but hasn’t yet made it to blood tests. It’s particularly important for patients in rural areas where access to healthcare is more limited.

All this means that a lab using Scopio equipment can reduce turnaround time by up to 60%, Hayut says.

Decision support system

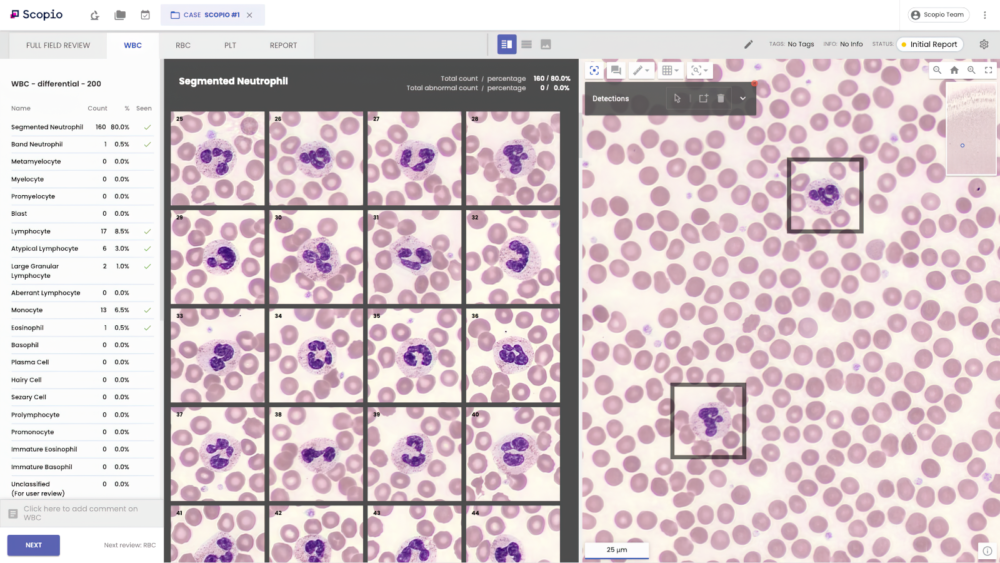

Once the data is digital, “you can apply AI to quantify the cells and then create a decision support system that helps the expert prepare a report,” Hayut adds. “The system pre-classifies the cells, but users can still make small corrections to the final report.”

The importance of quickly counting and analyzing cells in a blood smear cannot be underestimated – it’s the first stop in checking for cancer, infections and allergies.

“If there’s an immune reaction, you can see it in the white blood count,” Hayut explains.

Existing automated tests for CBC (complete blood count) can only differentiate between five main classes of cells. Scopio’s AI can get up to 16 classes with 96.3% efficiency, 87.8% sensitivity and 97.6% specificity.

The system has been validated at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center as well as the University of Pennsylvania and Brigham and Women’s hospital in Boston.

Hayut stresses that Scopio doesn’t make diagnoses but rather presents the data to a patient’s physician to interpret, just as in radiology or ultrasound procedures.

Hayut likens the product interface to Google Maps. “You can zoom in and zoom out and there’s also a pre-classification screen that predicts, for example, which cells are neutrophils and will then show them on the screen. Everything is classified by the AI. The expert just needs to review it and make sure the AI did a proper job in preparing the report.”

Solving the bottleneck

Hayut didn’t go into Scopio expecting to build a scanner – he was studying towards a PhD in applied physics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

“We thought we’d just buy a scanner,” he tells ISRAEL21c, “but once we started looking for something that scans the slides, we understood that there were very limited solutions. So, we set out to solve the bottleneck of digitization first. But at the same time, we’re creating new high-quality data.”

Last February, Scopio raised a $50 million Series C round, bringing the total investment in the company since its founding in 2015 to $84 million.

The Scopio team now numbers over 100, with most in Tel Aviv plus a few in the United States. Hayut cofounded the company with Erez Na’aman, who serves as chief technology officer.

Does Hayut have an opinion on Theranos, the ill-fated Silicon Valley company that claimed its machine could make hundreds of disease diagnoses from a single drop of blood?

“The good thing about Theranos is that they convinced people this is an interesting problem to look at. But they did a terrible job in executing, claiming things that were just not true.”

Hayut points out that, unlike Theranos, Scopio is already FDA-cleared, is working with the regulatory authorities, and is not involved in point-of-care service as Theranos was with its Walgreens wellness centers. Scopio’s business model is to sell direct to labs.

“We have a huge pipeline of customers waiting to get the production unit. We see a lot of excitement from the market,” Hayut says.

“This is good for humanity,” he concludes, “and also a huge market opportunity.”

For more on the future of tele-hematology, click here.