Think of it as the world’s oldest and largest jigsaw puzzle: Images of about 200,000 fragments of ancient Jewish documents, held in 67 separate locations across the world, are being matched up digitally by a powerful computer network in the basement of Tel Aviv University.

At the rate of half a million comparisons per minute, the task ran from May 16 through the end of June.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

This awesome accomplishment of the Jerusalem-based Friedberg Genizah Project finally will allow scholars – and anyone else with Internet access – to examine complete pages of documents retrieved more than a century ago from the legendary Cairo genizah.

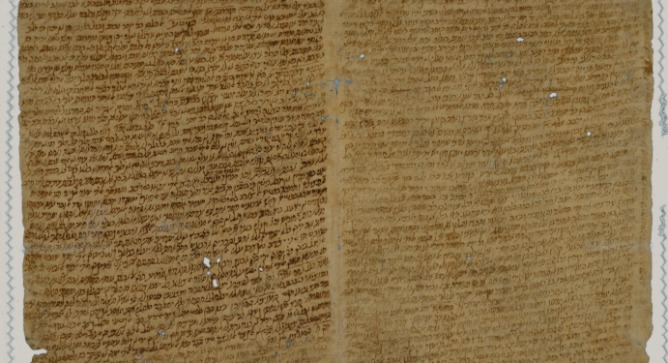

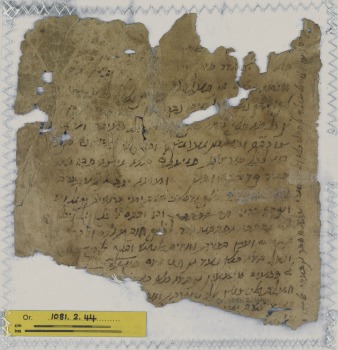

In this crypt in the old Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, Egypt, Jews discarded records and religious writings between the eighth and 17th centuries. They range from sacred texts to letters, poems and receipts giving a glimpse into medieval life in the Middle East.

Most of the trove was in fragments that ended up scattered among libraries and private collectors over the years. Putting them together in their original form seemed impossible and only a few scholars found “joins” among the pieces.

“The project has been waiting 120 years until someone could solve the riddle of the Cairo genizah, and my heritage gives me a special connection to the project,” says Cairo-born Prof. Yaacov Choueka, chief computerization scientist for the Friedberg Genizah Project, launched in 2006 by Albert Dov Friedberg of Canada in a joint venture with the Jewish Manuscript Preservation Society of Toronto.

How to match up the fragments?

Choueka tells ISRAEL21c that the original goal was to assemble computerized image files of the entire contents of the famous genizah.

The first hurdle was obtaining permission from every holder of genizah fragments to digitize and put the manuscripts on the Internet. At this time, the only one yet to give permission is the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg, which has about 1,000 fragments.

Fifteen programmers created the largest library of digitized historical manuscripts in the world, with about 450,000 digital images (there are several views of some pages included) and sophisticated software to view and manipulate the images. Some 3,000 people are registered on the site.

But there was more to be done.

At the end of 2008, in collaboration with professors Lior Wolf and Nachum Deshwitz of Tel Aviv University’s Blavatnik School of Computer Science, the Friedberg team decided to tackle the major problem in genizah research: how to join fragments of documents from different locations.

“There is no way to know if a piece I’m studying has a brother fragment somewhere,” says Choueka. “It takes imagination and scholarship and luck. We found a way for the computer to help in this task, using techniques from artificial intelligence and image analysis.”

They built a complex system that enables a computer to compare two images of handwritten fragments and determine the probability that they were written by the same scribe. Once this was possible, they realized that it could be done not just on a by-request basis.

“Why not try to match every genizah image to every other to solve this problem once and for all, rather than when a scholar is seeking help with a particular fragment?” Choueka reasoned.

From the alleys of Cairo to the Internet highway

“We had to do a lot of preparation because this is a gigantic operation, matching each of about 350,000 images to each other – the other 100,000 cannot be matched – requiring about 15 billion comparisons done by computer.”

Such a task was only possible thanks to a network of hundreds of supercomputers at the university.

“This is the breakthrough: implementing what we’ve prepared for a few years. When the results come in with all the joins, it will be the starting point of another research,” says Choueka, professor emeritus of computer science at Bar Ilan University.

The Friedberg Project assigned four researchers and several programmers to this effort. One of the researchers is Choueka’s son Roni, who holds advanced degrees in Talmudic studies and computer science.

Choueka muses that had the collection been found in any other city of the world, it might not have been as exciting for him.

“It’s the personal connection that I cherish,” says Choueka. “When I present the project, I usually say ‘From the alleys of Cairo to the Internet highway.’ And not just the manuscripts, but myself as well. I was 20 when I left Egypt, so I can read more or less naturally all the manuscripts in the genizah, which are mostly in Arabic written in Hebrew characters. Not many others can do this.”

At 77, Choueka is now starting to digitize old Babylonian Talmud manuscripts with the hope of building a website where people can view the variant texts of every chapter and a synopsis of the entire work. He estimates it will take five or six years to complete.

“Time is the sole remaining obstacle left between age-old mysteries and revelations on the verge of being discovered,” according to the Friedberg Genizah Project website.