As astronauts go farther and farther into space, a comprehensive understanding of how the changes in gravity impact them is crucial.

How does being in space change people? And how does being in space affect their medicines?

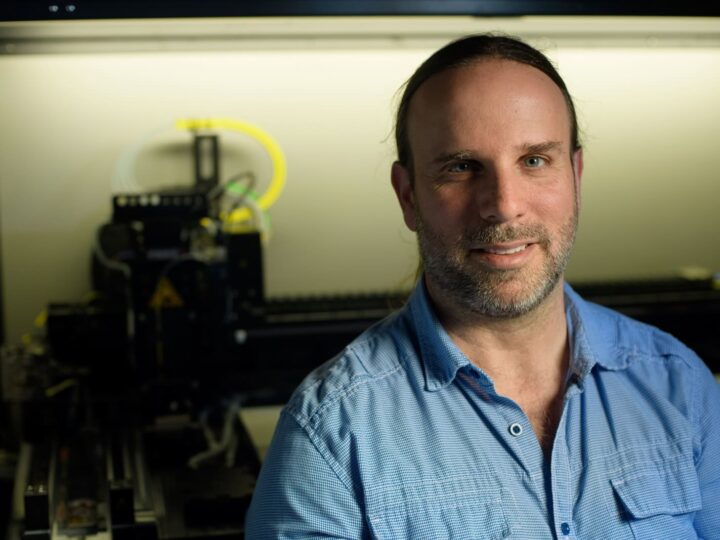

These are some of the questions that Prof. Sara Eyal of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem wants to answer.

Eyal is creating a space simulator lab at the university’s School of Pharmacy to research how gravity (or lack of it) in space affects medications.

Working with an international, multidisciplinary team of 15 scientists, engineers and researchers, she is also developing experiments to be used on SpaceIL’s mission, Beresheet 2, scheduled to launch sometime in 2024 or 2025.

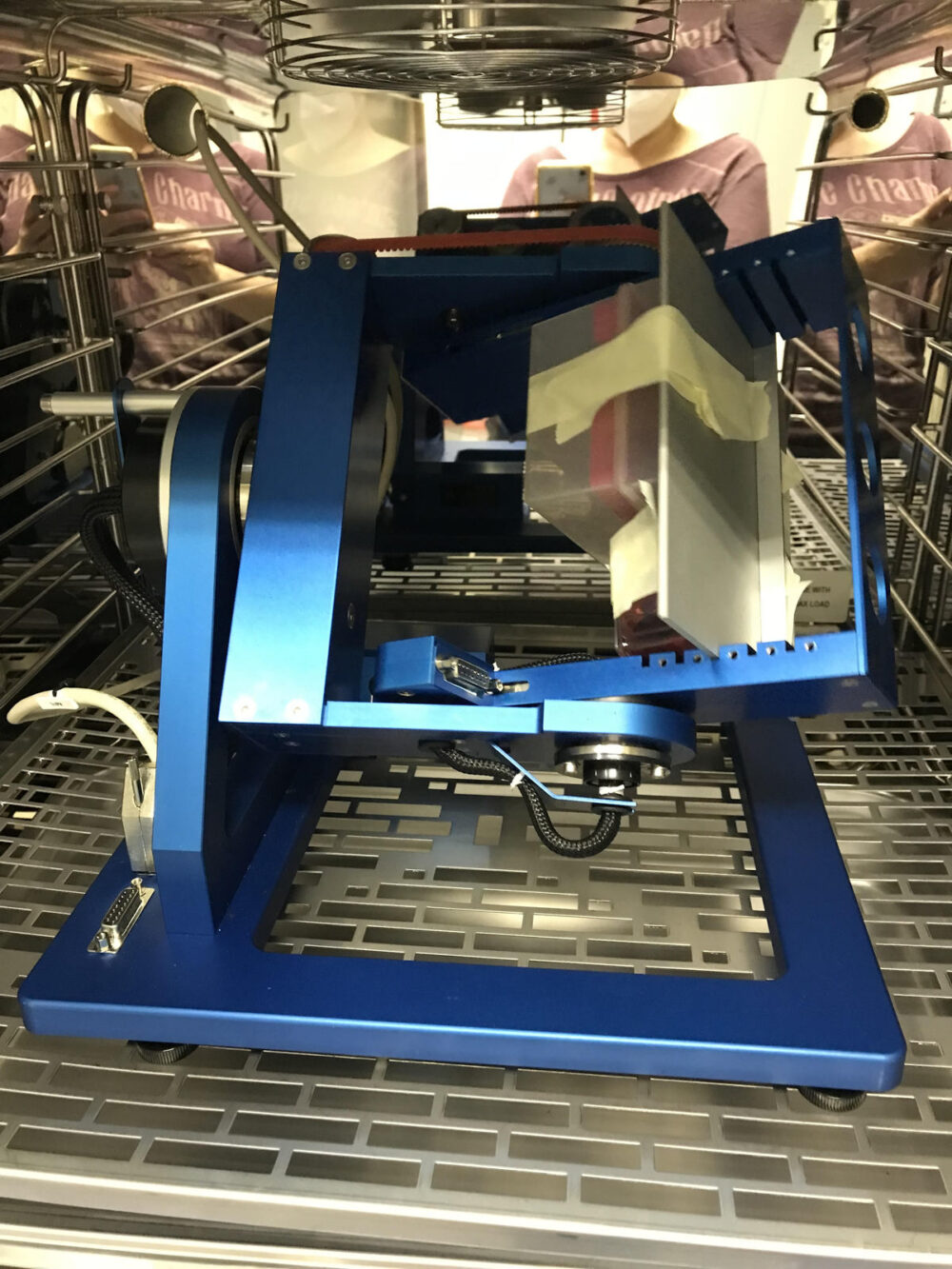

The space simulator lab is “the size of a printer,” Eyal tells ISRAEL21c. It can simulate the amount of gravity on the Moon, which is 1/6 of the amount of gravity on Earth, and approximate the gravity levels in space, generating gravity levels as low as 1/1000 of those on earth.

Eyal’s team will use it to test various medications that might be used on space missions.

“We are researching to make sure that the drugs are stable during the duration of a space flight,” Eyal said. “Some drugs may decay faster in space.”

Diseases develop in space

On previous space flights, astronauts took an average of 20 doses of different medications per week.

Eyal explained that when astronauts start their career, they’re healthy, but they may develop diseases the longer they are in space.

“We know that space itself induces diseases, accelerates aging, and changes the human heart, brain and other tissues,” she explains.

“Almost every system changes in space. Some of the changes are temporary and some are of long duration.”

The risk of long-term space travel is still great. “It can lead you to be very sick,” she said.

The twins study

Eyal cited the study of twin astronauts Mark and Scott Kelly that NASA performed in 2017. Mark Kelly stayed on Earth for a year while Scott Kelly was aboard the International Space Station for the year.

In space, Scott Kelly developed a 25 percent shrinkage in the left ventricle of his heart. His telomers, the caps on the end of a line of chromosomes that protect the DNA, became elongated. NASA researchers believe that spaceflight is associated with oxygen deprivation stress, increased inflammation, and shifts in nutrients that affect genes.

What happens when astronauts get sick in space? Eyal, who worked at the University of Washington in the United States and at the Israeli-Swiss company SpacePharma on space medicine projects, recounted that when one astronaut got sick on the International Space Station, NASA was able to send him anti-coagulant drugs.

Astronauts on the ISS can be evacuated within 48 hours. However, in the next few years, if astronauts go into deeper space, for example to Mars, it would be a three-year commitment, and Eyal said, “you can’t evacuate anyone and you can’t send drugs.”

Fingerprints of drugs

The researchers plan to include in the experiment antibiotics, drugs for treating pain, drugs for treating motion sickness (“a common symptom for astronauts”) and psychiatric drugs that help maintain astronauts’ psychological wellbeing during their many hours of isolation.

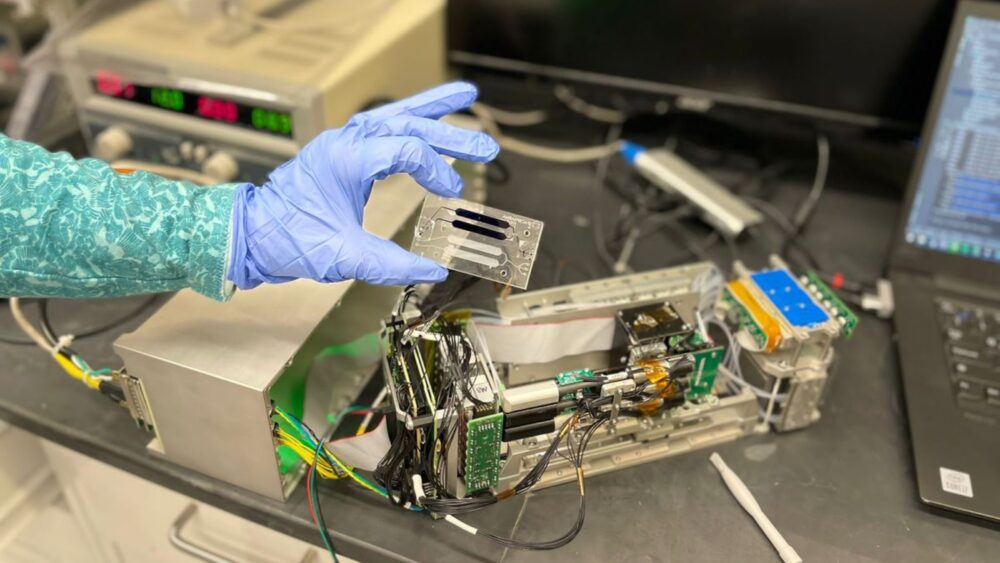

The team is developing an instrument to detect the “fingerprint” of each drug, “the unique signal each molecule generates during its measurement, which translates into a wave-like diagram that no other drug produces.”

These fingerprints will be transmitted to Earth through Beresheet 2 “to determine what happens to drugs in space,” said Eyal.

Her team includes Prof. Virginia Wotring from the International Space University, who was the chief pharmacologist of NASA, as well as Prof. Jan Jehlička from Charles University, Prof. Peter Vandenabeele from Ghent University and Prof. Aharon Oren from the Hebrew University – all experts in Raman spectroscopy (the method to detect the drug fingerprint in space); Tamar Stein, a Hebrew University astrochemist; and Prof. Ran Ginosar, an expert in deep-space electronics from the Technion and the founder of Ramon.Space.

The miniaturized lab is being developed by SpacePharma. The researchers coordinate all activities, and integration of the lab into the orbiter of Beresheet 2, with the engineers of SpaceIL.

Kidneys in space

“Everyone asks me if I would like to go into space and I tell them, ‘No way,’” Eyal said. “Even a bus makes me feel sick.”

Eyal, who was born and raised in Tel Aviv, said that as a child she used to collect flowers and leaves and make “medical solutions.”

She studied at the Faculty of Agriculture at Hebrew University because she was interested in agriculture. She had an interest in beekeeping because her husband, Yonatan, kept bees until she discovered she was allergic to bee stings.

She then changed direction and received a PhD in pharmacy at Hebrew University. She thought she would study anti-seizure drugs during her sabbatical at the University of Washington.

However, her advisers told her, “‘There’s been a slight change. We are going to work with NASA and study kidneys in space’.”

No going back

The experiment on renal metabolism in space was launched to the ISS in 2019. Eyal was invited to attend the lift-off at the NASA launchpad in Florida.

“Once you see that, you can’t go back,” Eyal said. “I wanted to explore how such tremendous changes in environmental conditions affect the human body.”

Eyal says that the lack of gravity “suddenly changes everything,” citing what happens to basic elements like fire and water in space.

Microgravity is the new frontier for research.

“I hope to develop my own technology for how to use microgravity to help people with diseases on Earth, maybe epilepsy,” Eyal said.

“My true passion is helping people. Maintaining the people on our planet is our first priority.”