An Israeli startup has developed a potentially game-changing surveillance camera that can both monitor a panoramic field and zoom in on details.

In the movie Enemy of the State, protagonist Will Smith unknowingly receives a computer cartridge with damning evidence of a government cover-up. For the rest of the film, he is relentlessly pursued by federal agents who use stunning surveillance systems to track his every move in fine detail. The only problem: Such technology doesn’t exist in the real world, beyond the fantasies of filmmakers. Or does it?

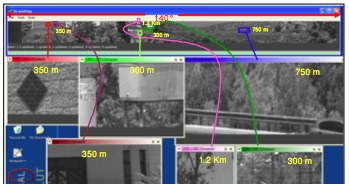

A small Israeli startup has developed a potentially game-changing, high-tech solution where a single surveillance camera can monitor a panoramic field of view and zoom in on any spot in real time with exceptional clarity.

The company, Adaptive Imaging Technologies, calls its invention a “panoramic telescope,” and aims to shake up the global security space – from borders to transportation hubs and even to large sporting facilities.

The company won the “Most Promising Startup” award from the Global Security Challenge last year, has received a $100,000 cash grant from the US Department of Defense, and already has orders, even though its flagship camera is still only in a pre-prototype stage.

It’s all in the pixels

Gideon Miller, Adaptive Imaging’s genial CEO, describes the workings of his technology to ISRAEL21c, explaining that unlike the consumer cameras most of us are familiar with that have somewhere around 10-megapixels, the Adaptive Imaging camera has a full gigapixel (that’s 1,000 megapixels) of raw resolution. With its telescopic lens, the camera can take in a very wide field, one which usually would require a much larger number of individual cameras.

But no software can handle a gigapixel of data at once, Miller explains. Adaptive Imaging’s trick is that those million pixels are spread out evenly across the camera’s view space. Then, if the camera operator wants to zoom in on any particular spot – say, a border fence or an individual face in an airport security line – the pixels can be focused on that target, resulting in a remarkably clear picture, while de-emphasizing less critical parts of the scene.

And, again, because there are so many potential pixels to draw upon, the camera can zoom in on multiple images simultaneously. An operator might choose to set the camera to only look at faces and not torsos or sky, for instance.

Adaptive Imaging’s Panoramic Telescope can be deployed in three different modes. The first is to set the camera to monitor specific areas in advance. This is useful if you want super-high resolution on the gate to a building complex.

In a second model, the operator pans and zooms manually – here the value proposition is that a single telescopic camera can replace multiple units, resulting in significant savings.

In the final model, software can instruct the camera to only detect motion, such as an infiltrator prowling along the border. The camera automatically zooms in whenever there is something suspicious, while not wasting bandwidth and storage on areas where not much is happening.

$6 b. market for surveillance cameras

The one drawback is that the camera only works in real time. It can’t zoom in on a pre-recorded video with the same level of clarity, as that would be ‘after the fact.’ “It’s all a matter of tradeoffs,” says Miller. “That would require a level of computing power that maybe only NASA has. You can’t have a free lunch.”

And that would also put the price of the camera – which will sell for “a few tens of thousands of dollars” (Miller won’t commit to a precise figure yet) – out of the range of most non-space age installations.

According to Miller, the Adaptive Imaging camera is equivalently priced to other high-end cameras on the market, but he adds that: “The camera itself is a relatively small part of the costs of a whole project.” Each camera needs its own towers, mounting, communications and electricity. “The more cameras you have, the more maintenance you’ll need and the more failures there will be,” he notes.

The market is certainly a big one. Adaptive Imaging estimates the demand for surveillance cameras at $6 billion.

The company has received a small amount of financing from the Chief Scientist’s Office (“enough to help with patenting,” Miller says). Is it looking for more funding? Miller is undecided. With orders from both military and commercial organizations, he says the company could manage without raising additional capital, although he can imagine a scenario where more cash allows the company to build a “pro-sumer” product at hundreds rather than thousands of dollars.

The techie behind the system

With world attention focused on airport security, the Adaptive Imaging camera could also be an effective alternative to the sticky issue of profiling. “We can compare faces with a black list and flag a particular threat in real time,” Miller points out.

Adaptive Imaging’s CEO is not the techie behind the system. That honor goes to Argentinean immigrant Eli Yakov, an old-timer in the field of image technology and robotics. Yakov built a system for dental imaging in the late 1990s and hooked up with Miller, then a corporate strategy consultant, who showed it to Kodak.

“They were quite amazed by what he had done,” Miller recounts. When Miller moved to Israel in 2001, the two formed a partnership.

Another company founder is Yitzhak Pomeranz who was CTO at Scitex Vision and is now part of the innovation group at storage disk manufacturer SanDisk.

Based in the small town of Yokneam in northern Israel, Adaptive Imaging Technology aims to deliver a full prototype by the end of 2010. Will it live up to the sci-fi promise of movies like Enemy of the State? Not quite yet. But it’s a panoramic zoom in the right direction.