After spending an average of $2.5 billion to develop a single new drug, sometimes pharma companies have to pull it from the market due to a bad outcome that was not detected in clinical studies.

That’s what happened in 2000, when a promising Type 2 diabetes drug called troglitazone led to idiosyncratic (unexplained) liver damage in one of every 60,000 users.

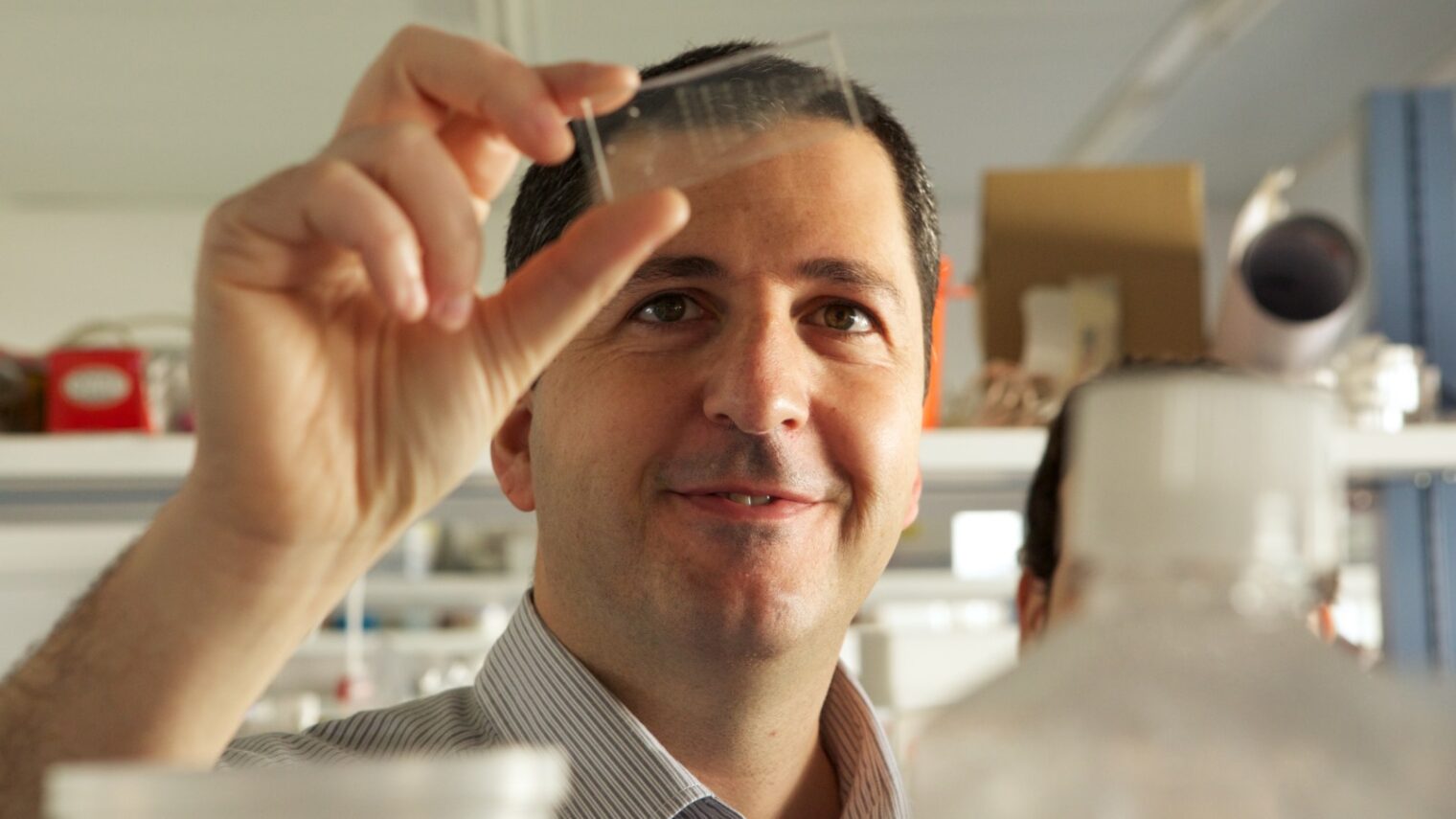

The troglitazone mystery wasn’t solved until March 2016, when a novel “liver-on-a-chip” platform developed by Hebrew University of Jerusalem Prof. Yaakov Nahmias revealed what no animal or human tests could: even low concentrations of this drug caused liver stress before any damage could be seen.

“It was the first time an organ-on-chip device could predict information to help pharmaceutical companies define risk for idiosyncratic toxicity,” Nahmias tells ISRAEL21c.

Shortly before that study, Nahmias’ liver-on-a-chip had revealed a new mechanism for acetaminophen (Tylenol) poisoning.

Given that about 16 percent of all FDA-approved drugs eventually show unexpected toxicity, Nahmias recognized the potential of his smart human-on-a-chip platform.

He licensed the technology from the university and spun off Tissue Dynamics to provide toxicology analysis of drugs and cosmetics.

L’Oréal was Tissue Dynamics’ first customer in October 2016. Major brands such as Unilever are expected to follow suit as they seek alternative models to evaluate new products now that European laws prohibit cosmetics makers from animal testing.

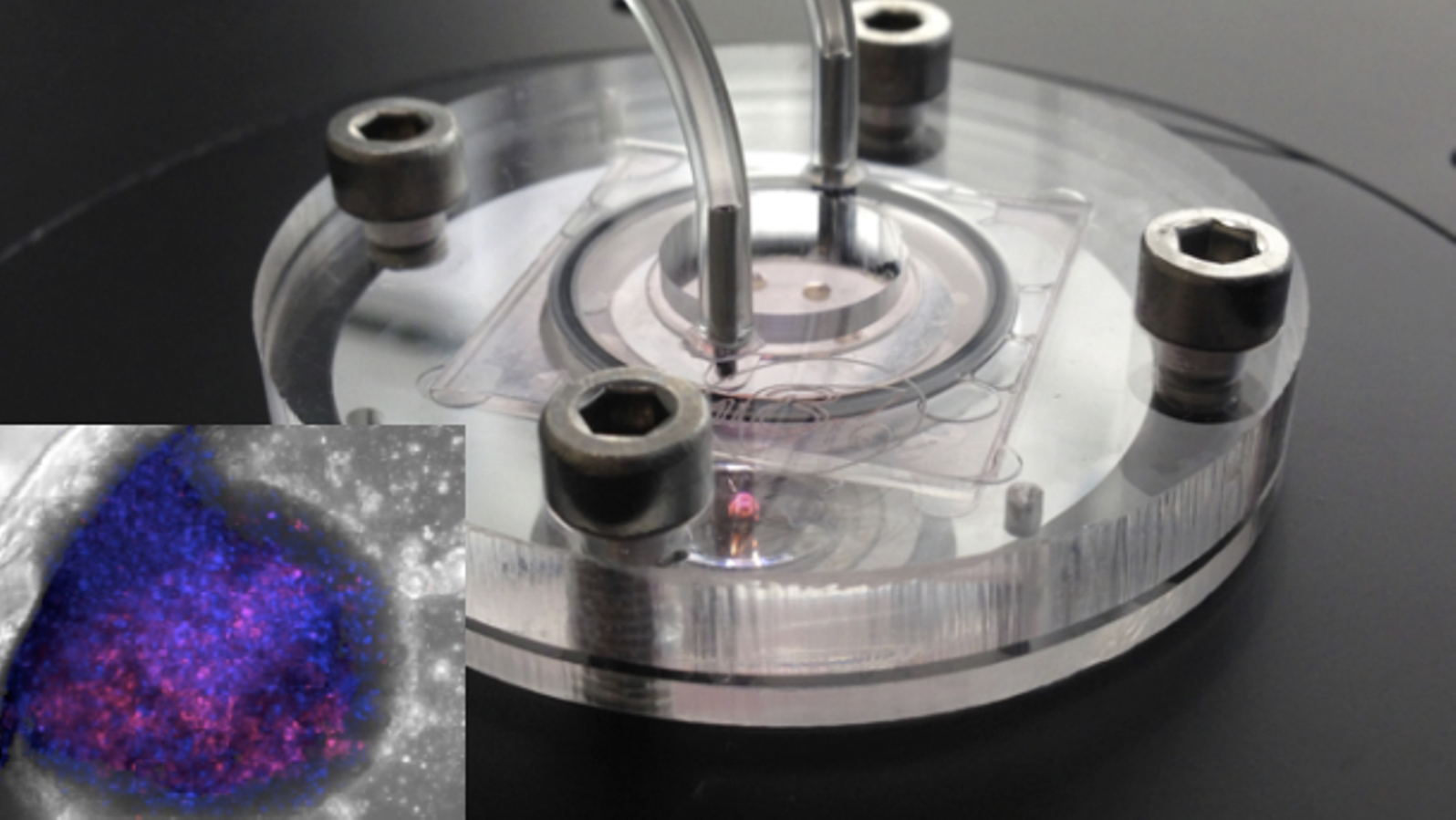

Tissue Dynamics’ liver-on-a-chip – as well as heart and brain chips coming soon – could greatly reduce the number of animal tests, the amount of time for drug evaluation and the astronomical cost of drug development. Not to mention the billions that pharma companies pay in damages when a drug proves harmful.

As a young faculty member at Harvard Medical School in 2009, Nahmias built the technology for one of the first human-on-a-chip companies, HuREL. So he is confident that Tissue Dynamics — the first human-on-a-chip company in Israel and one of few in the world — can do what none of the others can do.

“All of the other companies are focused on mimicking animal experiments. They place cells in a device, give it drugs and then open it to look at damage or death, which is what people are used to doing with lab animals,” Nahmias explains.

“This is a major disadvantage because those human-on-chip models can only find the type of damage you predict is going to happen. It doesn’t find the unexplained responses, and that’s the biggest problem for the pharmaceutical sector. We are unique in the field because no other model can even start to predict idiosyncratic damage.”

He explains that when a drug or protein is introduced to the Tissue Dynamics system, the changes they cause to the simulated cell are monitored in real time.

“If the change is fast, we know the drug introduced direct damage. If it happens over several hours we know the damage accumulates like in fatty liver disease,” says Nahmias.

Best/worst times to take medication

Nahmias won a $2.3 million European Research Council grant last September to develop the next generation of his liver-on-chip system, which mimics circadian rhythms –the daily ebb and flow of human metabolism.

“If we could generate a model for human metabolism that mimics complex physiology, we could develop drugs for obesity, diabetes or fatty liver disease that are impossible to develop today,” he says.

Tracking circadian dynamics will allow Tissue Dynamics to predict time-dependent toxicity — the best and worst times to give a drug based on the fluctuation of the enzymes that break down the drug in the body. Pharma companies currently do not have this information.

In 2018, the company expects to offer chips simulating a pumping human heart and a human brain that has functional neurons embedded with vasculature.

“Our goal is to have these three major organs, which are the target of a lot of drugs. In 2019 we will complete a large facility for manufacturing the chips,” Nahmias tells ISRAEL21c. “There is a lot of interest.”

Since that initial liver-on-a-chip was built in 2015, his lab has increased capacity and added more sensors and optimized controls. A complete metabolic analysis of a drug molecule that used to take about three months now takes about a week.

Chips and animals

Although human-on-a-chip offers many advantages over animal models, Nahmias does not believe this novel screening technology will replace lab animals completely.

“In animals we can look at specific neuronal damage and behavioral changes that we can’t really mimic on a chip. A chip can’t feel pain or behave erratically,” he says.

“However, we can probably drastically reduce the number of animal experiments. We could screen half a million different drug molecules through our system, and only those that work at the least concentration and cause the least damage could be taken to animal testing.”

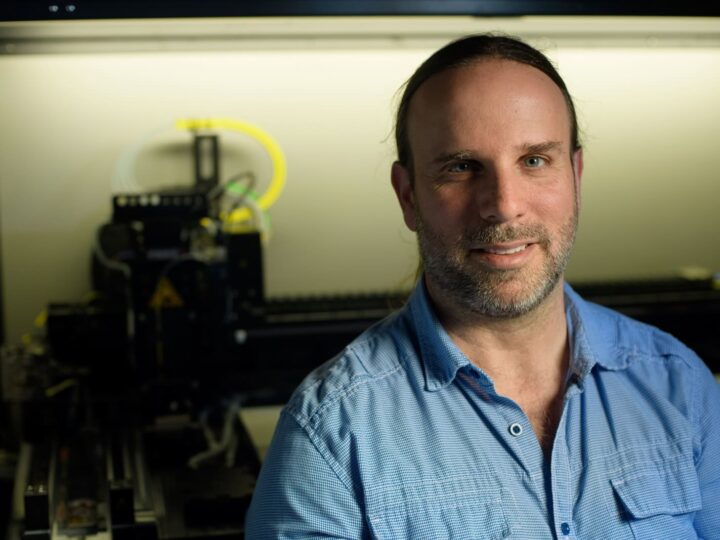

Nahmias is chief scientific officer of Tissue Dynamics, whose six-person staff includes CEO Ayelet Dilion Mashiah. He also directs the Alexander Grass Center for Bioengineering at the Hebrew University and won several prizes for his internationally recognized work in tissue engineering and nanotechnology.

For more information, click here