When a little lamb fell out of a truck bound for the slaughterhouse and broke her legs, her kindhearted rescuers knew just where to take her.

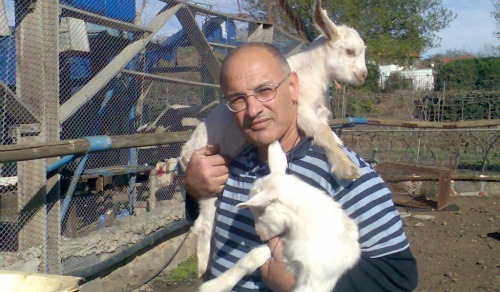

Babi Kabalo had already nurtured back to health a slew of ill or injured animals, including a half-blind filly and a donkey whose leg was blown off by a missile.

Kabalo and his wife, Tami, run Bel Ofri Farm in the small Golan Heights village of Kidmat Zvi. This unusual couple is known throughout the north for taking in unadoptable animals in addition to the goats, peacocks, pigeons, rabbits, marmots, guinea pigs, tortoises, chickens and ducks that live in a petting corner.

Actually, animals were never intended as the main focus of the Kabalos’ eco-farm, which they founded after their grown kids moved away.

“Ten years ago, our children went to the army and Tel Aviv and stayed there,” Tami says. “It was difficult for us because all you have up here is your family. So before they put us in a mental hospital” she jokes, “we decided to open our doors to tourists. And we built a new conversation with Christians and Jews coming from all over the globe to see us.”

Babi, a 54-year-old farmer, and Tami, a 53-year-old former Jewish philosophy and sociology teacher at ORT Hatzor Haglilit High School, used recycled materials to create a living museum of the Golan Heights lifestyle during the Talmudic period some 2,000 years ago. It encompasses a boutique winery, a reconstructed ancient olive press pulled by a mule, an organic vegetable patch, a working well and a restaurant with a clay oven.

Teacher, philosopher, jeweler

Guests can pick and stomp on grapes from the Shiraz vineyard, grind wheat kernels into flour, and press oil from olives. Tami shows them how to bake olive-studded whole-wheat loaves in the clay oven, sprinkled with herbs picked on the spot. She also demonstrates how to make cheese, a byproduct of the resident goat herd.

“We got a lot of goats as gifts, and when they started having babies I had to learn what to do with the milk, so I learned to make cheese,” she says. “Camembert, Roquefort, all kinds.”

Because Tami is still a teacher at heart – and holds a master’s degree in philosophy from Tel Aviv University – she turned her casual conversations with tourists into formal workshops on Jewish philosophical approaches to topics ranging from interpersonal relationships to devils and demons. She also offers instruction in sculpting, painting, collage and mosaics, and finds the time to design jewelry that Babi renders in silver.

For the children who visit, however, the biggest attraction is “Barboron’s Animal Petting Corner.”

The collection of disabled or injured animals there began with an abused white horse found hobbling on a broken leg near a Druze village. It was saved by an animal welfare organization and sent by a sympathetic donor to the Kabalos. Later it was joined by a half-blind filly and a sick older horse that didn’t eat for days.

The couple’s oldest daughter, Rotem, heard on the radio about a donkey whose leg had been blown off by a Katyusha rocket launched from Lebanon during the 2006 war. He was found wandering in the mountains near Safed and was going to be put to sleep. Rotem immediately faxed the authorities and assured them her father would adopt him. When she called Babi, he was already on his way.

Neither simple nor cheap

The Kidmat Zvi children who come every day before and after school to help Babi care for the animals named the unfortunate creature Katzefet (“Whipped Cream” in Hebrew), a conjunction of the words katyusha and Tzfat (Hebrew for “Safed”).

Osher (Hebrew for “happiness”), the lamb that fell off the truck, is now a healthy sheep and expecting a lamb of her own. The goat kids from the Kabalos’ flock love to cuddle with her at night. “We take care of Osher and she takes care of the kids,” says Tami with a laugh.

It’s neither simple nor cheap to rehabilitate injured, traumatized animals. But the Kabalos duo is adamant that “we cannot throw away these animal friends.” They rely on income from the workshops and from sales of their wines, cheeses and jewelry, plus occasional contributions and even short-term loans.

Tami and Babi met in the southern Negev city of Beersheba, where she was working toward her bachelor’s degree in behavioral science and he was serving in the army. They headed north following their 1978 wedding and helped build Kidmat Zvi, where Babi tended its vineyards and cherry and apple orchards.

When empty-nest syndrome set in, they turned their attention to learning crafts and building Bel Ofri, which is open Saturdays and holidays, plus weekdays by reservation.

“We like having a lot of life around us,” says Tami simply.