A rare benign tumor called LCH (Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis), found mainly in children under 10, afflicted a young hadrosaur in Canada over 60 million years ago.

This surprising discovery indicates that LCH is not unique to humans and has survived through the long evolutionary process, say Tel Aviv University scientists who studied the evidence.

“Researchers in North America studying dinosaur fossils identified large cavities, evidently created by tumors, in two tail vertebrae of a young dinosaur discovered in southern Alberta,” said physical anthropologist Hila May of the Dan David Center for Human Evolution at the Sackler Faculty of Medicine.

“The dinosaur belonged to the genus Hadrosaurus, also known as ‘duck-billed dinosaurs’ – herbivores common almost all over the world about 66-80 million years ago.”

The specific shape of the cavities caught the researchers’ attention: they were very similar to cavities created by LCH.

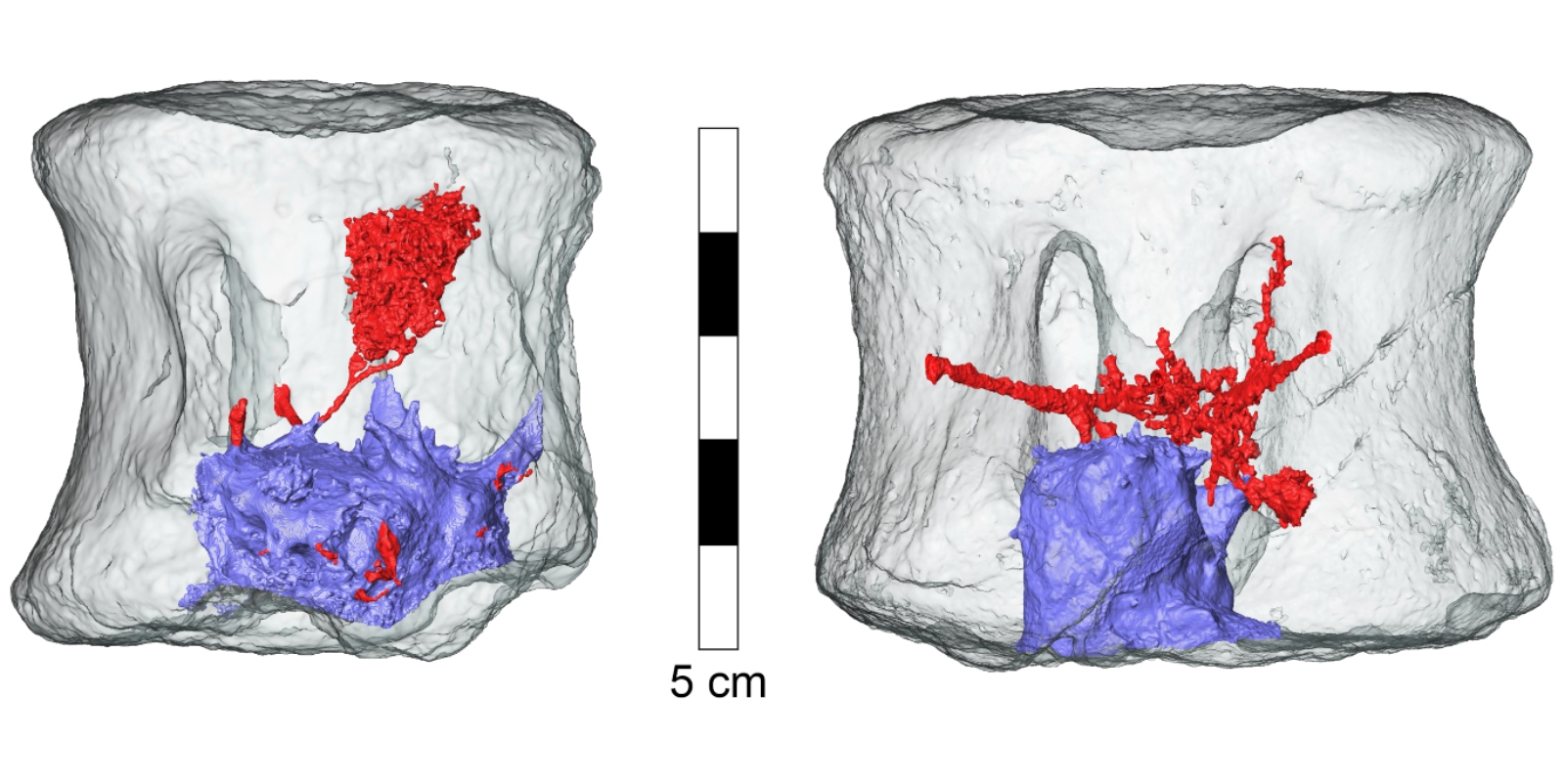

The dinosaur’s vertebrae were sent for micro-CT scanning at Tel Aviv’s Steinhardt Museum of Natural History.

“The scanner generates images with a very high resolution of up to a few microns,” said May. “We were able to form a reconstructed 3D image of the tumor and the blood vessels leading to it. The image confirmed in a high probability that the dinosaur did indeed suffer from LCH.”

Other contributors to the study include Prof. Bruce Rothschild of Indiana University; Prof. Frank Rühli of the University of Zurich; and Darren Tanke of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Alberta, Canada.

The paper was published February 10 in Scientific Reports.

“Research of this kind, made possible by current technology, contributes a great deal to Evolutionary Medicine – a relatively new field of research which investigates the development and behavior of diseases over time,” said Prof. Israel Hershkovitz from the Dan David Center.