Digging through refuse from ancient civilizations in Israel’s Negev Desert, PhD student Daniel Fuks looks for the ratio between grapes and grains. This tells him a lot about the civilization’s shift from thriving to falling.

“Ancient garbage tells us a story, a story we should listen to because it’s our story,” says Fuks.

When faced with health and environmental crises, farmers would plant fewer grapevines and more grains as they switch from cash crops to subsistence crops.

And that is exactly what Fuks found in his study of nearly 10,000 seeds of grape, wheat and barley retrieved and counted from 11 trash mounds at three sites in the Negev.

“The Byzantines didn’t see it coming. We can actually prepare ourselves for the next outbreak or the imminent consequences of climate change.”

The seed proportions provide evidence of a significant economic downturn on the fringe of the Byzantine Empire.

The downturn was likely caused by factors we can relate to today: a major pandemic and an enormous volcanic eruption in the sixth century CE that kicked offa record-cold decade.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reconstructs the rise and fall of commercial viticulture in the middle of Israel’s arid Negev desert.

Fuks, a PhD student in Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology at Bar-Ilan University, led the study as a researcher in Prof. Ehud Weiss’ Archaeobotany Lab, and as a team member of the Negev Byzantine Bio-Archaeology Research Program, “Crisis on the Margins of the Byzantine Empire,” headed by Prof. Guy Bar-Oz of the University of Haifa.

Less wine, more bread

Bar-Oz’s team, guided by field archaeologists Yotam Tepper and Tali Erickson-Gini from the Israel Antiquities Authority, sifted through the trash of Byzantine-era farmers in threeNegev Highlands communities to discover when and why the agricultural settlements were abandoned.

“In the ‘Crisis on the Margins’ project, we excavated these mounds to uncover the human activity behind the trash, what it included, when it flourished, and when it declined,” explained Bar-Oz.

The seeds found in those excavations were examined by the Bar-Ilan University Archaebotany Lab — the only lab in Israel dedicated to identifying ancient seeds and fruits.

The many grape seeds in the ancient trash mounds support previous scholars’ suggestions that the Negev was involved in export-bound viticulture.

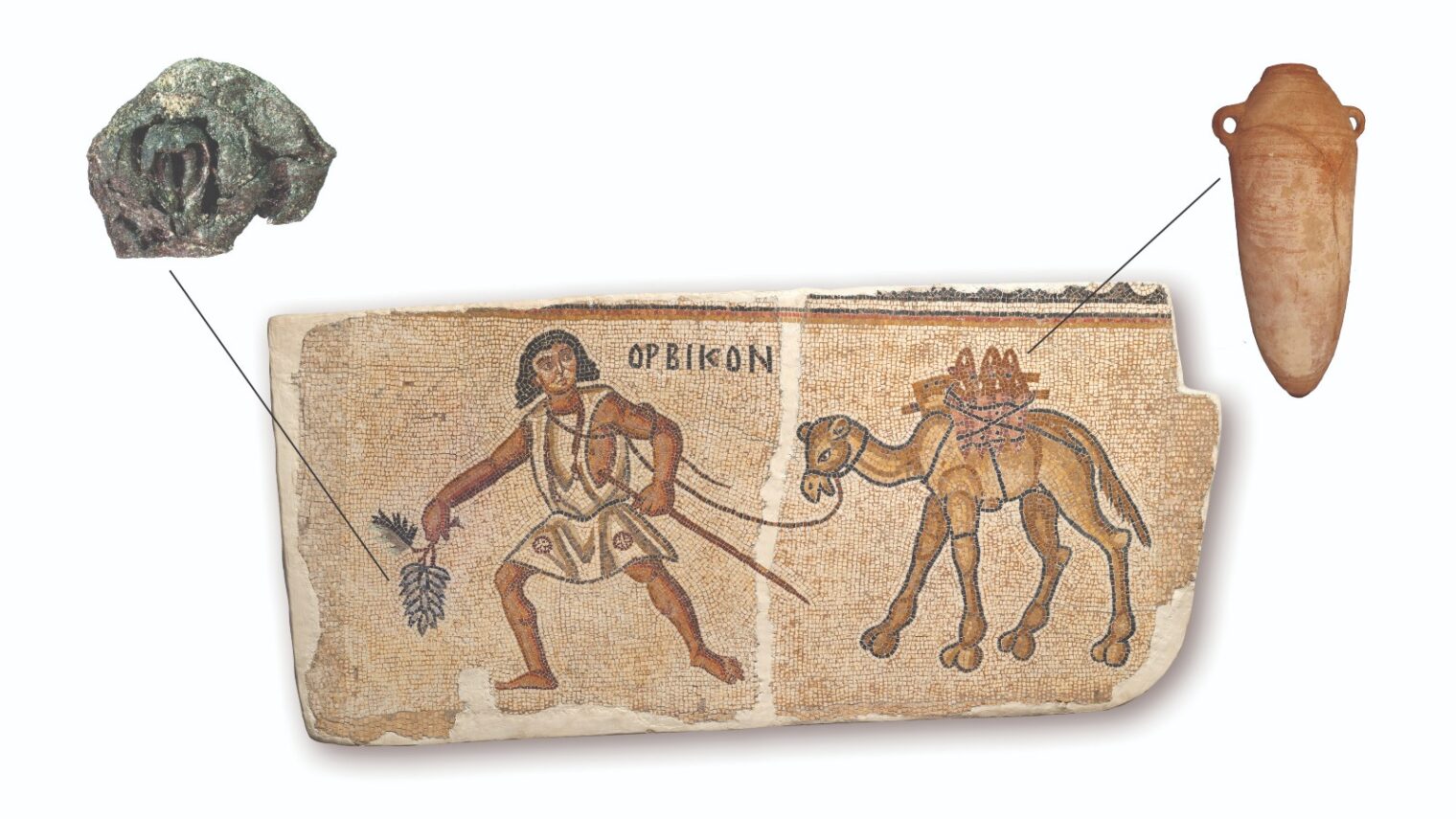

Byzantine texts mention vinum Gazetum(Gaza wine, a sweet white wine exported from the port of Gaza throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. This wine was generally transported in “Gaza jars” found in large quantities in Byzantine Negev trash mounds.

Fuks searched for trends in the relative frequency of grape pips in the rubbish.

“Imagine you’re an ancient farmer with a plot of land to feed your family. On most of it, you plant cereals like wheat and barley because that’s how you get your bread. On a smaller part, you plant a vineyard and other crops like legumes, vegetables and fruit trees, for your family’s needs.

“But one day you realize that you could sell the excellent wine you produce, for export, and earn enough cash to buy bread and a bit more. Little by little you expand your vineyard and move from subsistence farming to commercial viticulture.

“If we look at your trash and count the seeds, we’ll discover a rise in the proportion of grape pips relative to cereal grains. And that’s exactly what we discovered: A significant rise in the ratio of grape pips to cereal grains between the fourth century CE and the mid-sixth century. Then suddenly, it declines.”

Jars and pips

Fuks and Erickson-Gini checked for similar trends in the proportion of Gaza wine jars to bag-shaped jars, the latter less suited to camelback transport.

Indeed, the rise and decline of Gaza jars tracked the increase and decrease of grape pips.

The researchers concluded that the commercial scale of viticulture in the Negevsome 1,500 years ago, as seen in the grape pip ratios, was connected to Mediterranean trade as seen in the Gaza jar ratios.

The authors explain that pandemic and the earthquake “detrimentally impacted the Negev economy, even while trade at nearby Gaza may have continued.”

If the plague reached the Negev, it would have harmed production capacity and the availability of supplies and agricultural laborers.

“It appears that agricultural settlement in the Negev Highlands received such a blow that it was not revived until modern times. Significantly, the decline came nearly a century before the Islamic conquest of the mid-seventh century,” commented Bar-Oz.

What lesson does this hold for us today, in the midst of Covid-19 and climate change?

“The difference is that the Byzantines didn’t see it coming,” said Fuks. “We can actually prepare ourselves for the next outbreak or the imminent consequences of climate change. The question is, will we be wise enough to do so?”