We can only imagine what life might have been like for the Children of Israel, as they wandered the desert for 40 years following the exodus from Egypt. Or maybe we don’t have to imagine.

The desert traveled by the Israelites exists to this day. And each year, Jews relive their experience by housing themselves temporarily in open-roofed booths during the holiday of Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles.

Plus, among the region’s populations live the Bedouin. Up until recently, these nomadic people lived in much the same way as did Moses and his followers – at least that’s how they were perceived by 19th century European photographers who captured images of a Holy Land that was peopled by seemingly biblical figures.

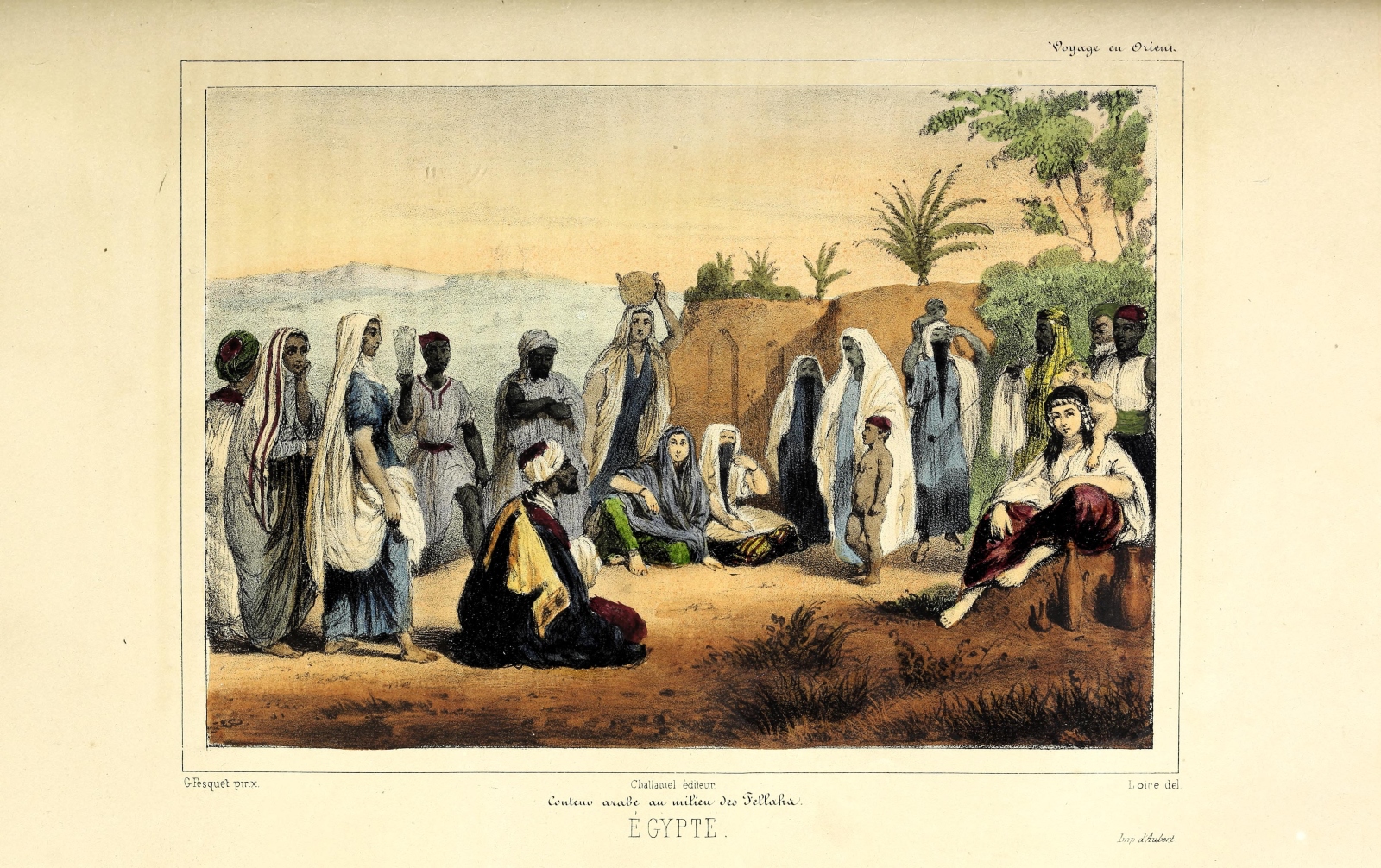

Photography arrived in the Middle East almost as soon as it was invented in 1839. That year, French painter Horace Vernet and his nephew Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet traveled to the Holy Land to create daguerreotypes.

In 1842, Goupil-Fesque published an account of the journey, Voyage d’Horace Vernet en Orient. The book included lithographs based on the original daguerreotypes that, unfortunately, did not survive.

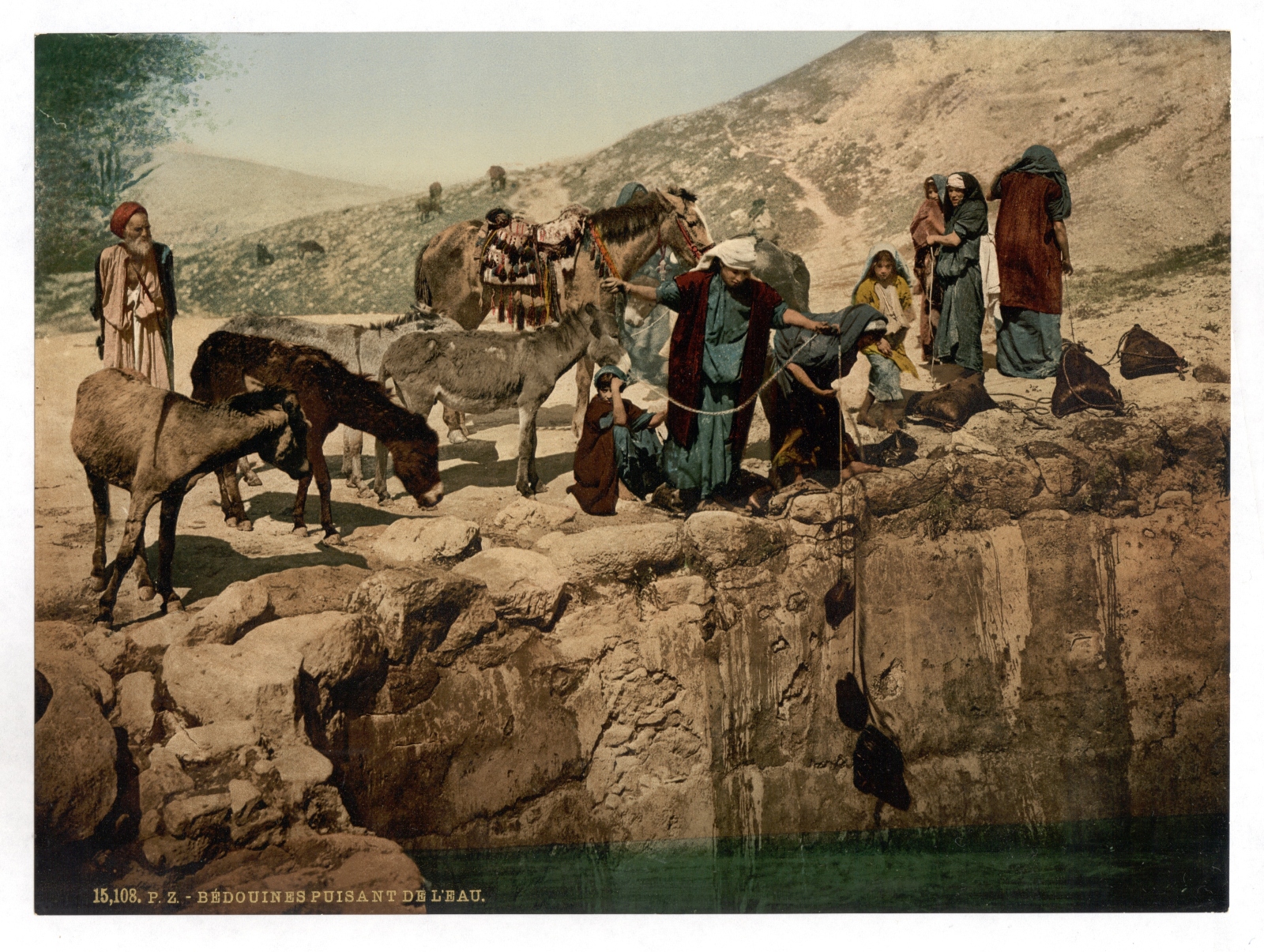

French photographer Félix Bonfils moved to Beirut in 1867 where he opened a photography studio with his wife, Lydie.

Bonfils’ documentary work in Lebanon, Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Greece and Turkey– he was one of the first to employ the new Photochrom method of color photography – is today considered of great importance in the study of history and archeology.

At the time, however, the studio was known for its high-quality images and albums of biblical scenes – some with figures costumed and staged, others in their usual surroundings – that were sold to tourists inthe Holy Land.

The American Colony was a utopian Christian sect of religious pilgrims who emigrated to Jerusalem in 1881 from the United States and Sweden. To support themselves, the group produced souvenirs and opened a store and a hostel for travelers (today the luxurious American Colony Hotel).

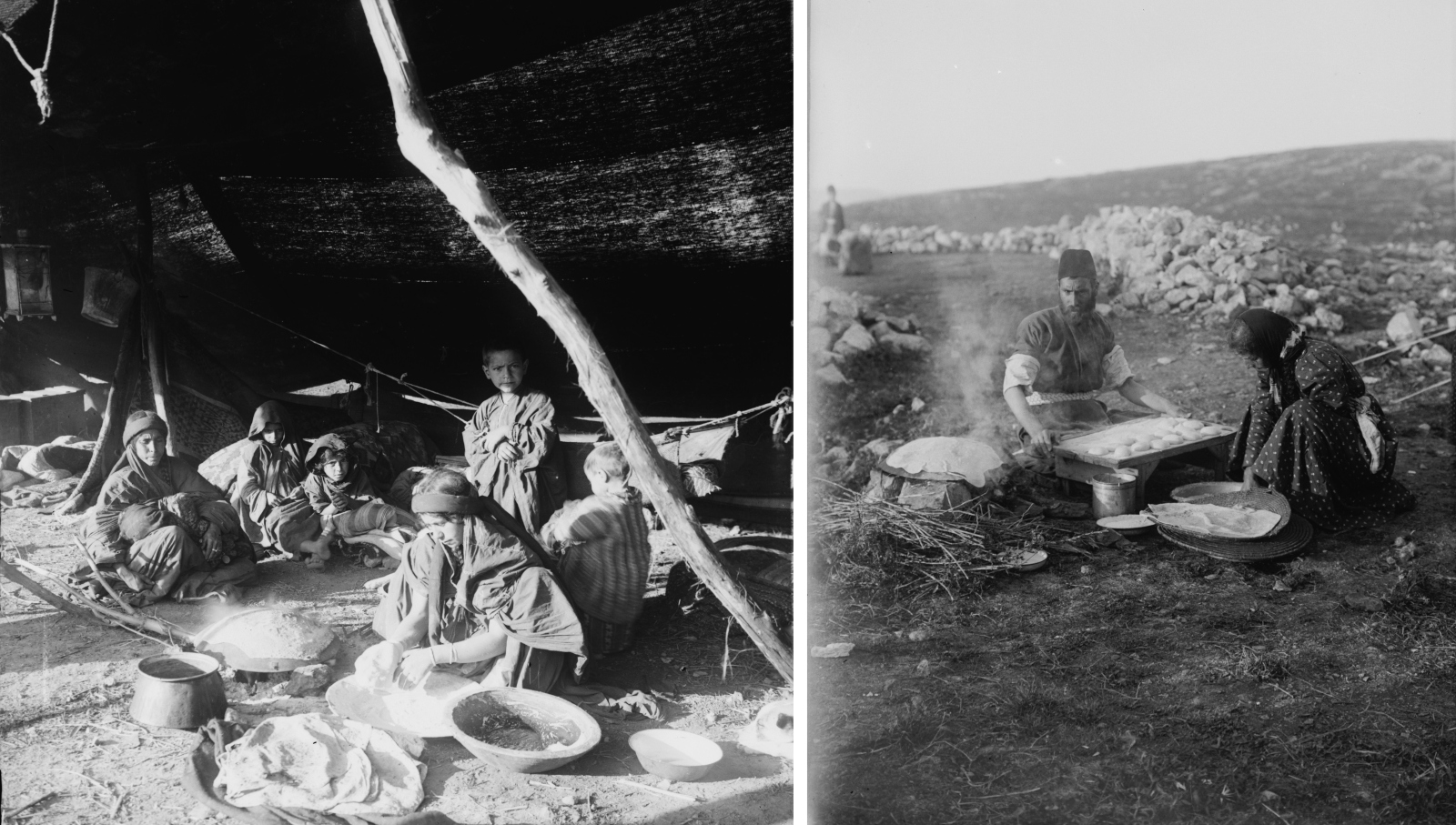

In 1898, having had great success in selling photos documenting the German Kaiser’s visit, members of the American Colony established the Photo Department.

Although it was an important profit-generating branch for the American Colony, their photographers also had a sense of spiritual mission. Their vast output over five decades of activity included documentary photos taken while retracing the steps of biblical figures.

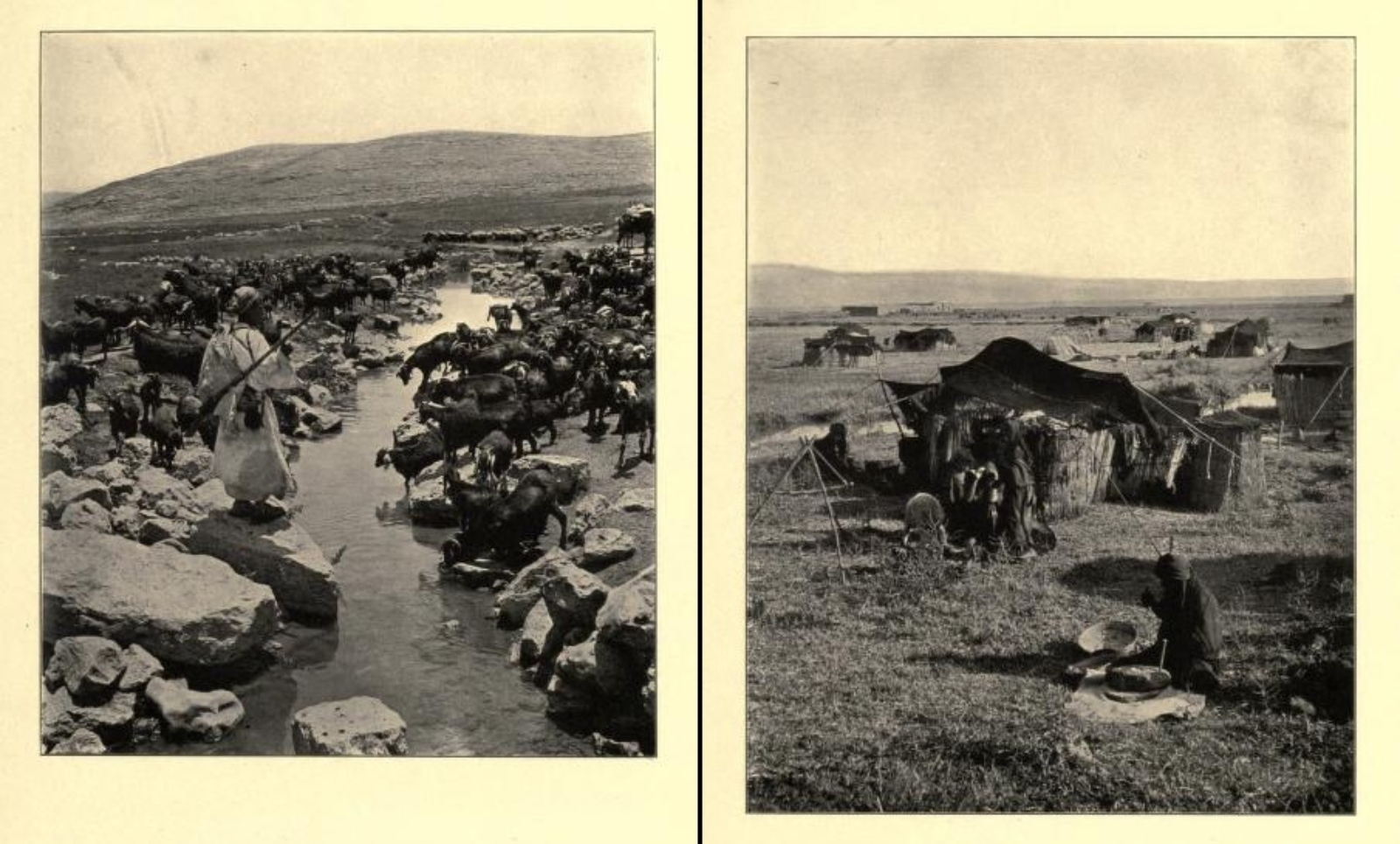

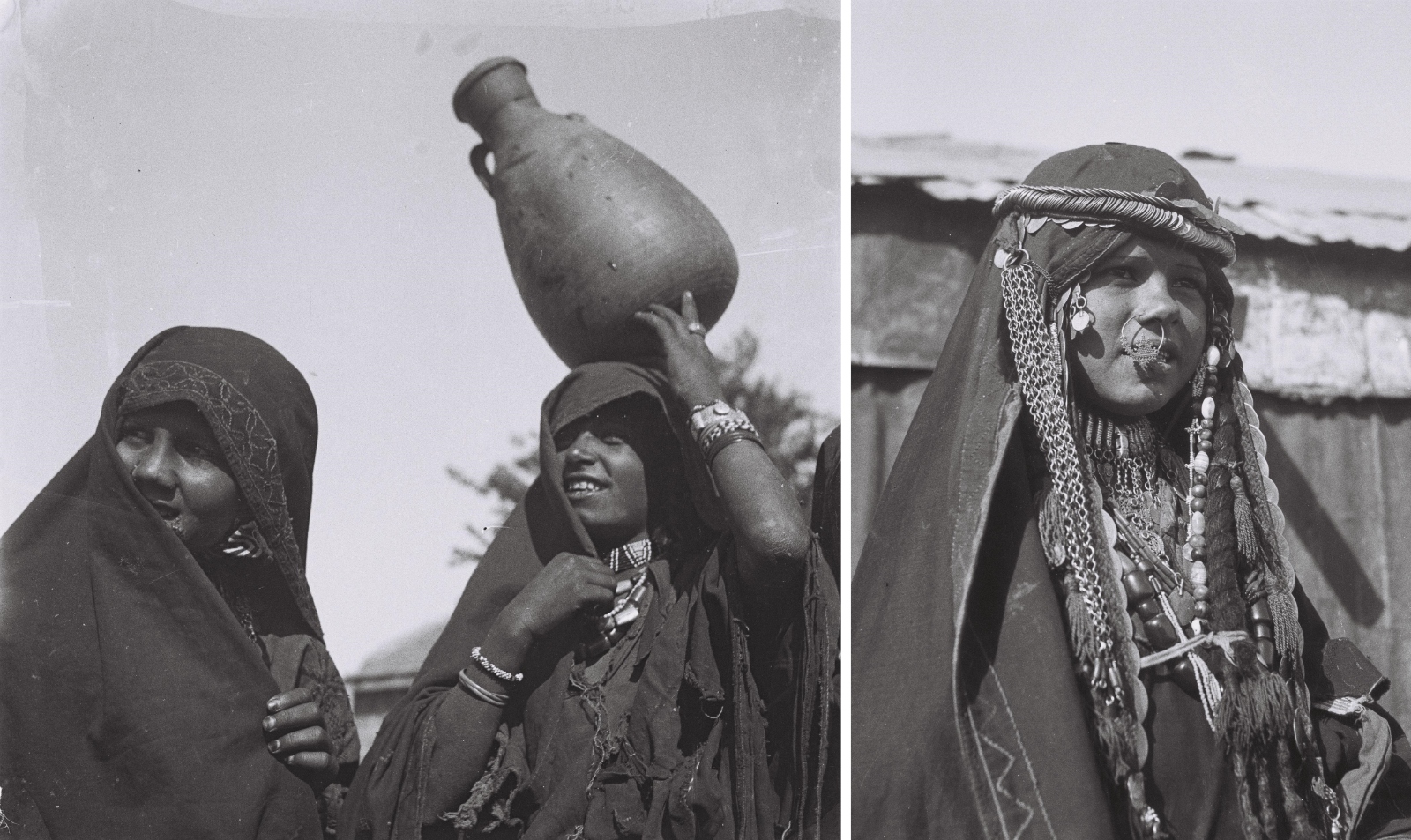

By the end of the 19th century, almost 300 pilgrims had photographed the Holy Land. In 1901, New York City-based painter and photographer Dwight L. Elmendorf made the trip. His book, A Camera Crusade Through the Holy Land, comprised 100 full-page photo plates. Many of the pastoral images, like those of Bedouin goat-herders and basket-weavers, were evocative of biblical times and were accompanied by appropriate Bible quotations.

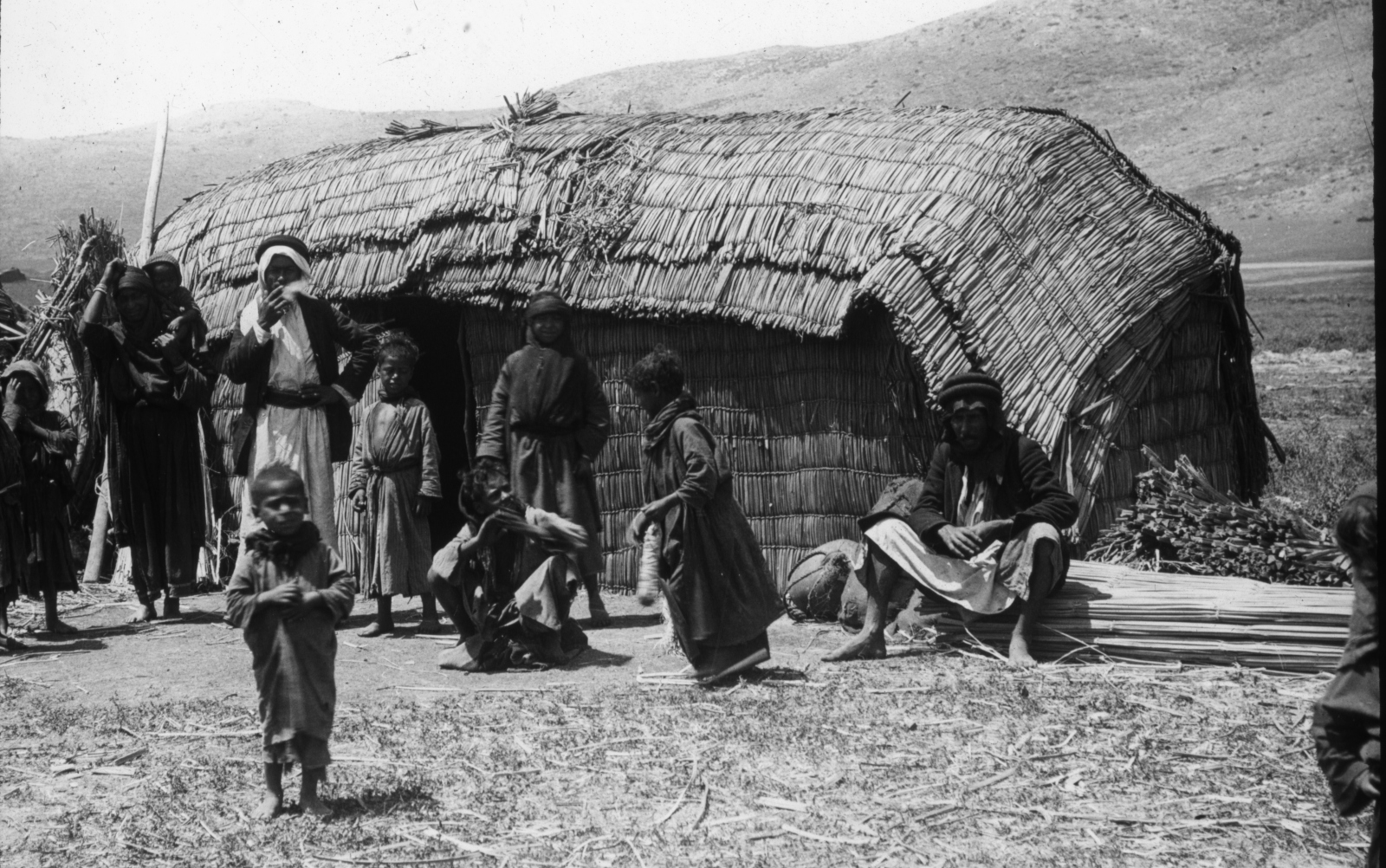

In the early 20th century, American Colony photographers traveled to the Galilee and documented the local Bedouin living in straw mat booths.

In 1940, their photographers again visited the Hula Valley Bedouin, this time producing a series of photographs about the production and marketing of straw mats.

For the Zionist movement, the Bedouin way of life was a tangible manifestation of the Jewish people’s connection to the Land of Israel. Here weredesert sheepherders, just as Moses was when he lived among the Midianites. And over there – women bearing clay jugs and wearing gold finery, just as in the book of Exodus.

The native desert dweller ideal was romanticized and many young newcomers, en route to life on a new settlement, would have themselves photographed in Arab garb to send back to their families as proof of their acclimatization.

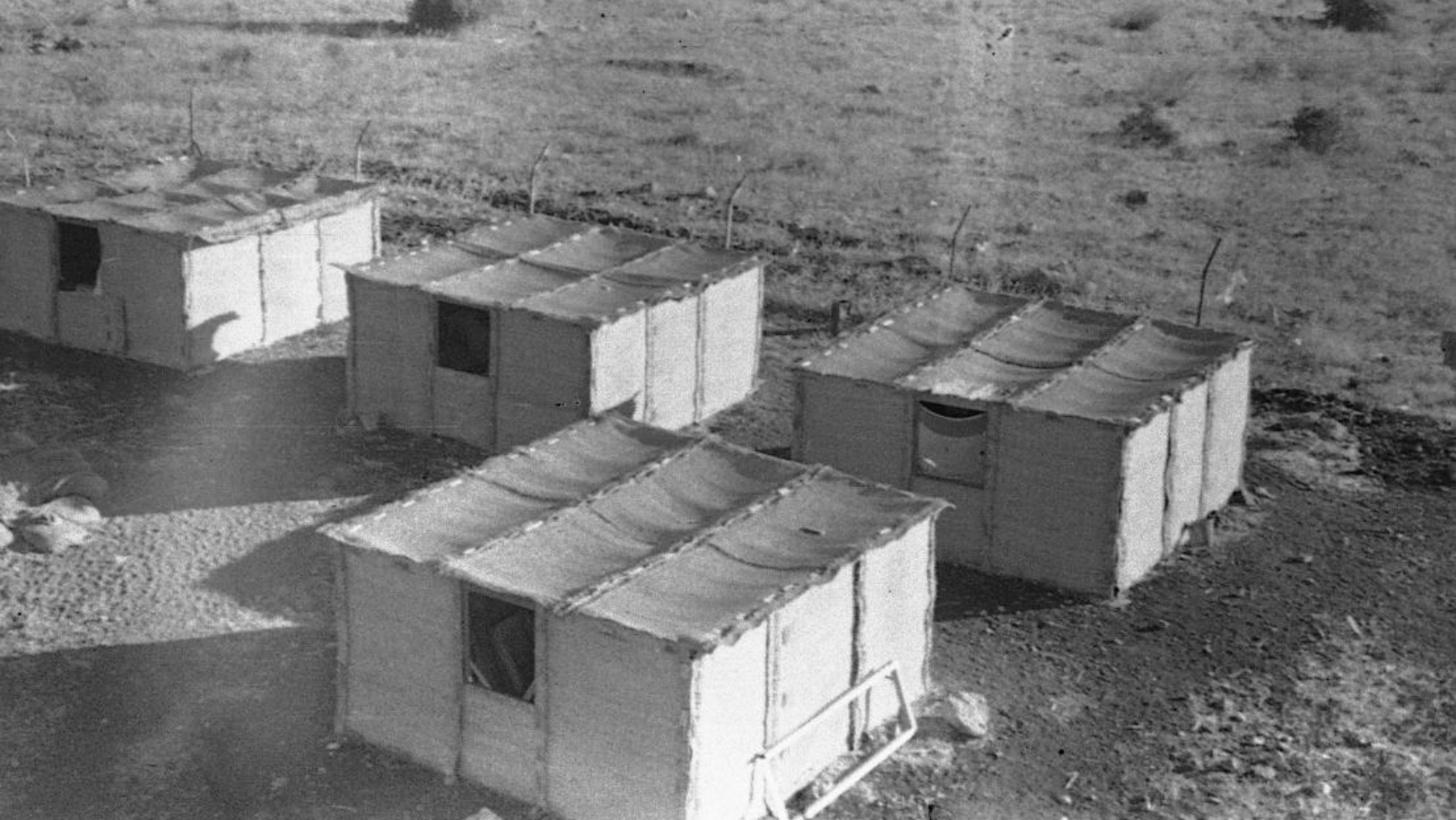

On a more practical note, the members of Kibbutz Hukok took inspiration from the Sukkot holiday “tabernacles” when building temporary housing after the 1948 War of Independence.

Initially, the early settlers looked to the local Bedouin for guidance about herding and agriculture, but ancient ways were quickly supplanted by modern methods. Photographers like Zoltan Kluger, who worked chiefly with the JNF-KKL and Keren Hayesod (United Israel Appeal), took pictures juxtaposing the old with the new.

Israeli’s romanticized love for the Bedouin ideal only intensified after Israel regained control over the Sinai desert in 1967. For the better part of two decades, Israeli flocked to places like Nueiba, Dahab and Sharm el Sheikh to hike, dive, detach and decompress while staying at the Bedouin tent camps that inevitably sprang up to accommodate tourists with activities like camel rides, festive feasts, belly-dancing, and more.

After control of the Sinai reverted to Egypt, these activities moved to the Arava and Negev regions. There, during the Sukkot holiday break, one will find Israelis in huts, tents, or zulas, and eating pita made the old-fashioned way – as it was when the Children of Israel wandered in the desert and lived in sukkot.