It’s hot on Kibbutz Tirat Zvi. Blazingly, unbearably hot. On June 21, 1942, the thermometer hit 54 degrees Celsius (129.2 Fahrenheit), the highest-ever recorded temperature in Asia.

Even if Tirat Zvi has never surpassed or equaled that world record since then, during a typical summer the daytime thermometer hovers around a sizzling 40C (104F), “cooling off” to about 38 in the evening.

“I’m plotzing here. The air conditioner is already on at nine in the morning,” says Shelly Ganiel, who moved to Tirat Zvi in 1970 from New York as the bride of a kibbutz native. When she volunteered there several years earlier, guest quarters were so sweltering that they threw water on the wooden floors to cool the rooms down.

Tirat Zvi was founded in July 1937 by religious German and Polish immigrants who had no idea that the Beit She’an Valley, in which Tirat Zvi and several other kibbutzim are located, lies 220 meters (722 feet) below sea level, making it not just one of the hottest places in Israel, but also one of the hottest places on Earth. And that July, says Ganiel, was among the hottest on record.

When she asked her father-in-law why they settled in such an extreme location, he replied, “We were young and stupid; we didn’t know where the Beit She’an Valley was, and we were very idealistic.”

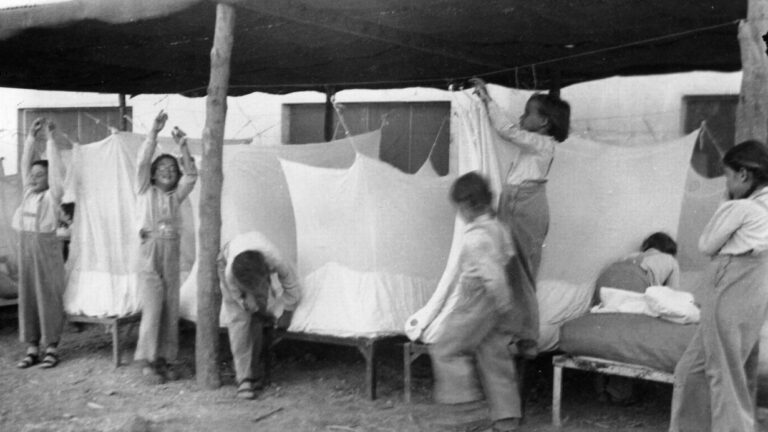

The early kibbutzniks began farming the fields and orchards well before dawn every day but Saturday, broke for showers and naps midday and then returned to work in the late afternoon. They cooled themselves in pools of water gathered from underground natural springs – the official name of the Beit She’an Valley is Emek Hama’ayanot (Valley of the Springs) — and on the worst nights they slept outside, covered with mosquito netting.

In the 1950s, each tiny kibbutz house got a fan to help cool the main room by day and the bedroom by night. Withstanding the heat became a sort of badge of honor.

When air conditioners slowly started to be installed in 1968, “There were people who said air-conditioning was too bourgeois and the kibbutz would fall apart,” Ganiel tells ISRAEL21c wryly.

Today, Ganiel says, “You go from your air-conditioned house to the air-conditioned synagogue to the air-conditioned dining hall to the air-conditioned tractors introduced in the last 20 or 25 years.”

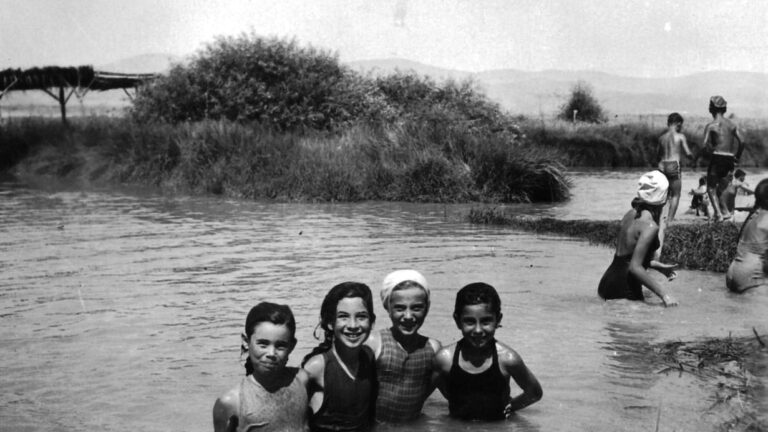

Once the kibbutz installed a swimming pool, it became a favorite summer hangout. Ruchama Seliger grew up on Tirat Zvi and recalls that although swimming on the Sabbath is normally forbidden, the kibbutz rabbi made a blanket exception for the children.

“Being in the water part of the day was a given, and we learned not to be outdoors during the hottest hours,” she says. “But children react very differently to heat than adults. I don’t remember it being awful, though I do remember nights being sweaty and hot.”

When Seliger was a teenager in the 1950s, the kibbutz invented the taftefet (dripper). Installed on the little houses’ outdoor windowsills, the system consisted of two screens filled with wood chips or straw, with a hose dripping water on the filling. Occasional breezes would go through the wet straw and enhance the cooling effect of the electric fan in the room. “It brought the temperature down to 90 from 100,” says Seliger.

Ganiel notes that kids raised on the kibbutz, including her husband, do not seem as bothered by the heat. What’s more, Tirat Zvi’s 27 vacation rooms (air-conditioned, of course) are booked through the summer.

She finds the heat more oppressive these days. “It used to be very dry here so it was like going into a sauna, but over the years every kibbutz and moshav in the Beit She’an Valley built at least one reservoir to use the natural springs for drip irrigation, and that introduces a tremendous amount of humidity.”

However, Tuvyah Gross, the unofficial weather-keeper on nearby Kibbutz Ein Hanatziv, says the moisture from the agriculture and fish ponds of the Beit She’an Valley assure that the mercury will never again climb as high as it did in 1942.

“The water evaporates and takes the heat with it,” he explains. “The average humidity here is 30 to 40 percent, which is considered comfortable. Eilat is usually a degree hotter than we are and it feels more oppressive because it’s so dry.”

Watermelon, the liquid savior

Other Beit She’an Valley communities are slightly higher in elevation than Tirat Zvi so their summer temperatures are a degree or two lower, but still beastly hot.

Ken Goldman, a world-renowned conceptual artist who grew up in Brooklyn and moved to Kibbutz Shluchot 30 years ago, jokes that he copes by keeping his head in Fahrenheit mode. “Forty-three degrees Celsius may be 109 Fahrenheit, but in Fahrenheit 43 is cold. That makes it easier.”

For the hundreds of children from Israel and abroad who come to his summer camp, Kayitz Bakibbutz, a Fahrenheit mindset won’t help.

“We have installed huge cold water coolers all over the kibbutz since our camp began 16 years ago, and our campers must carry water and wear hats at all times,” says Goldman. “Our secret weapon is cold watermelon. We grow our own here, and we go through so much of it at camp. It’s like a liquid savior.”

Camp days are scheduled so that the hottest times are spent in the air-conditioned gym or other indoor spaces, Goldman tells ISRAEL21c. “We try to do trips where they get wet, and if we go hiking we go at 5:00 in the evening. The kids never complain about the heat.”

Gross, from Ein Hanatziv, points out that Israel’s Arava and Jordan valleys can get just as hot as Beit She’an. Indeed, the thermometer hit 46C in the Jordan Valley’s Kibbutz Galgal in July 2012. “There are days it’s an absolute blast furnace and you just have to deal with it,” he says.