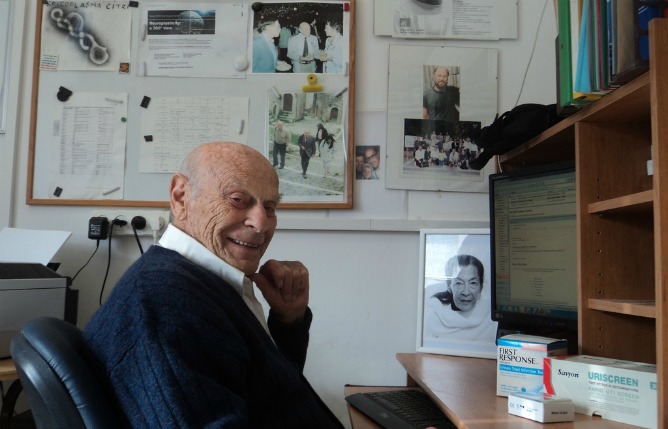

At 91, Prof. Nathan Citri offers no advice on how to achieve longevity. That he’s made it this far — with a mind so sharp he is still inventing innovative medical diagnostic kits — may be thanks to long walks or good genes.

He cannot know for sure, since the Nazis cut short the lives of his parents and his only sister.

“This country saved my life,” says Citri. In return, he continues to give Israel the best of his extraordinary knowledge in microbiology.

Born Natan Cytrynowski in Lodz, Poland, the future Hebrew University researcher was raised in a Hebrew-speaking home by Zionist educators.

“How many people spoke Hebrew at home in those days? Nobody else I know of,” he tells ISRAEL21c with a laugh. He vividly recalls visitorsmarveling that the Cytrynowski kids not only conversed in Hebrew but even cried out in Hebrew when they were upset. “I always say that my mother tongue is Hebrew even though my mother never made it to Israel.”

This unusual upbringing benefited Citri greatly when he left Poland for Palestine in 1937 through Youth Aliyah, a rescue organization in whichHadassah founder Henrietta Szold was active. He arrived at Ben Shemen youth village, a well-known training ground in the basics of kibbutzfarming.

“People always ask me if I knew [Israeli President] Shimon Peres,” he says. “But he was two years behind me and we didn’t socialize with the younger kids.”

Still searching for ways to save lives

Today Citri lives in a comfortable assisted-living residence on Szold Street, not far from the Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School atHadassah’s Ein Karem campus.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

He formally retired in 1989, but continued working at his home and university labs to answer the World Health Organization’s desperate call for a way to contain antibiotic-resistant bacteria that kill thousands of critically ill hospital patients each year.

Together with Naomi, his late wife and fulltime collaborator, Citri developed a prototype for bedside kits that detect and identify resistant bacteria from blood or urine, yielding lifesaving information within minutes rather than days.

He felt sure someone younger would replicate his idea, which he considered an obvious approach. However, nobody stepped up to the plate.

So in September 2011, seven months after Naomi’s passing, Citri went to London to show his concept to a world expert in the field. The Israeli already had consistent results obtained in Britain with prototype kits produced according to his emailed instructions.

[scrollGallery id=8 useCaptions=true]

The expert told Citri it could take two years to develop the invention. “I said, ‘Look at me. I don’t have that kind of time. We need to do this right now.’ And he gave me the names of two British companies with the technology to produce this kind of kit.”

The next day, the first rep to show up at his hotel said, “There have been countless failed attempts at solutions, and your idea is so simple and straightforward. We want it.”

The agreement, administered through Hebrew University’s tech transfer company, Yissum, has fast-tracked the process of gaining Europe’s CE Mark of approval for the kits.

Professor without a high school diploma

Citri never matriculated high school. Planning to be a pioneer farmer, he left school at the age of 15. But after volunteering in the British Army from 1942 to 1946, he heeded the call of Zionist leader Berl Katznelson to replace the lost intelligentsia of Europe.

“I felt it applied to me. My parents were intellectuals and could have contributed so much,” says Citri. “They were murdered at such an early age, and my sister wasn’t even 19.”

He was not qualified to enter the Hebrew University, but the Jewish Agency encouraged him to sit for the entrance exams anyway. In just six weeks, he managed to master the material and gained acceptance. He decided to study bacteriology.

“When I was about 10, a book called Microbe Hunters was translated into Polish and I read it. They became the heroes of my childhood,”explains Citri.

He earned his doctorate in 1954 and did research fellowships in London and Illinois before returning to the Hebrew University in a variety of posts, including academic vice dean of the medical school from 1982 to 1988.

Citri also chaired the committee tasked with translating life-sciences lingo for dictionaries published by the Hebrew Language Academy.

He met Naomi Zyk, a PhD from Montreal’s McGill University, when she was hired as his lab assistant during a stint at Harvard in 1962. For the next 50 years, she shared his life and his research.

Their son Ami, a neurobiologist, will join the Hebrew University in August with a double appointment as an assistant professor at the Silverman Institute of Life Sciences and at the Safra Center for Brain Sciences.

Miki, Citri’s daughter from a previous marriage, is a social worker at Hadassah. Her brother Yoav, a promising scientist, died in 1995.

Though the nonagenarian has known many sorrows, he remains upbeat and is working on another diagnostic kit whose details are still hush-hush. Ever fair-minded, he’s steering this project to the British company whose representative didn’t make it to his hotel fast enough to win the “superbug” kit contract.