You don’t have to be a professional spelunker to explore hundreds of ancient Beit Guvrin-Maresha caves between Beit Shemesh and Kiryat Gat in central Israel. Just put on a good pair of walking shoes.

Always a popular family destination, this 1,250-acre national park Israel was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in June 2014.

The main attraction for some 200,000 annual visitors is the manmade chalk caves — 200 in Beit Guvrin, 200 in Maresha and 80 in between. Over the course of 2,000 years, people used these caves as quarries, stables, granaries, storerooms, water cisterns, workspaces for pressing grapes and olives, cultic houses of worship, dovecotes, hideouts and gravesites.

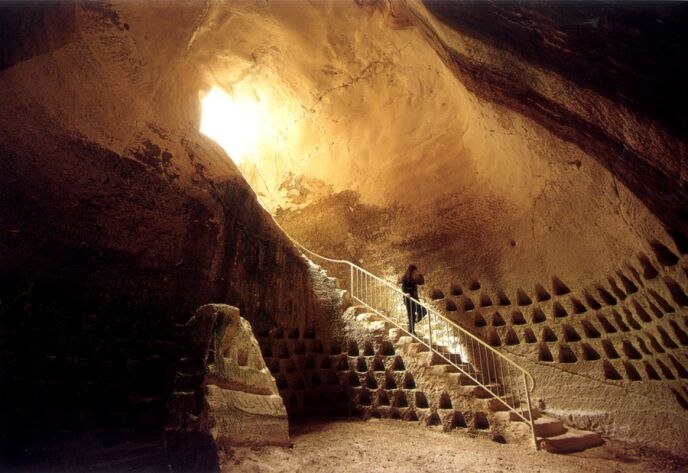

Tsvika Tsuk, chief archeologist of the Israel National Parks Authority, took ISRAEL21c through Beit Guvrin’s well-known Bell Cave complex — 70 connected bell-shaped quarry caves — on a hot summer day. The spectacular complex is as cool to see as to feel; the temperature goes down dramatically as you descend inside.

Tsuk confides that the Bell Cave is responsible for his choice of profession. In 1972, while hiking here with army buddies, he came across the remains of an ancient ossuary (human bone box). He eventually turned his find over to the Antiquities Authority, where it’s kept in storage with others like it.

The experience led Tsuk to Prof. Amos Kloner of Bar-Ilan University, who helped excavate Beit Guvrin-Maresha in the 1980s and 1990s and still is producing reports on the 480 caves. And it also inspired Tsuk to pursue a doctorate in archeology.

The Children’s Cave

Before we enter the Bell Cave, Tsuk points out the gray limestone, locally called “nari,” forming a layer over the softer chalk.

“Ancient people cut very small holes in the nari, which is approximately three meters thick, and when they reached the chalk they enlarged it and made all the caves,” says Tsuk.

“They made one bell shape and then another, and then connected them together. The ones along the sides are still preserved, while the ones in the middle collapsed.” The ruins of those collapsed caves are evident on the grounds of the park.

Arabic inscriptions from the early Islamic period and inscribed crosses from the Byzantine-Crusader era decorate the Bell Cave walls, testifying to roughly 2,000 years of activity here until the 11th century CE. Stick figures of a boy and girl, dubbed “The Twins,” appear high up on one wall, eons before the present floor of the cave was reached.

“We think that a worker on break, when his boss wasn’t looking, drew his children in low relief, and that’s why this is nicknamed the Children’s Cave,” says Tsuk. For unknown reasons – perhaps in reference to a wife of King David, given the area’s proximity to the battle of David and Goliath – the Bell Cave complex also is called the Abigail Cave.

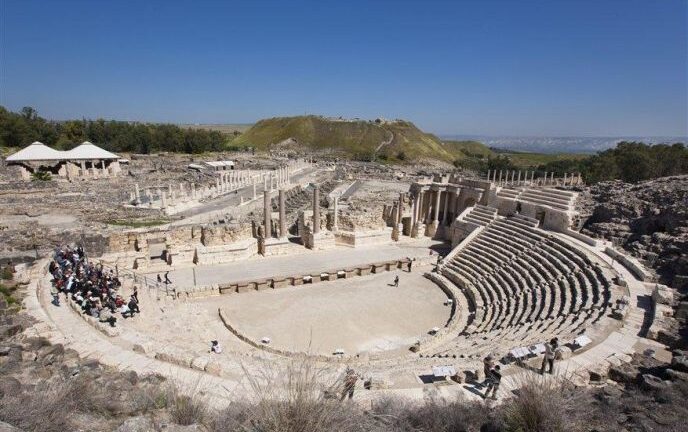

Strollers and wheelchairs can access the Bell Cave, as well as the site’s Roman amphitheater and visitor center.

World Heritage Site

The 480 caves of Beit Guvrin-Maresha are part of a wider area, reaching from the Ela Valley down nearly to Beersheva, known as the Land of a Thousand Caves. Actually, Tsuk estimates the number to be an astonishing 10,000.

The undeveloped site was always accessible to the public, and archeological research was taking place as far back as 1900.

But Beit Guvrin-Maresha wasn’t user-friendly until the Israeli government invested in a massive project from 1988 to 2002, employing many of the newly arrived immigrants from the Soviet Union to excavate and clean the caves, and build trails, signage, restrooms, picnic areas, parking lots, eateries and a visitor center in cooperation with the Jerusalem architectural firm of landscape architect Shlomo Aronson.

The caves range in size dramatically. “The largest one, No. 61, takes 15 minutes to walk from one end to the other,” says Tsuk.

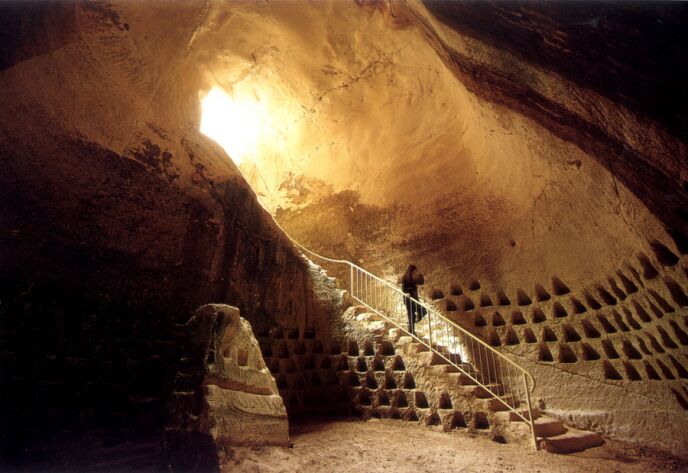

The national park is replete with 85 columbarium caves, once used for raising doves and still inhabited by many pigeons. We visited the main Columbarium, the most impressive of the Tel Maresha caves, dug in the third century BCE. Some 2,000 nesting niches are carved into the Columbarium, reflecting the ancient premium put on their meat, eggs, dung and value as sacrificial offerings.

Also of note are the Sidonian burial caves from the Hellenistic period (third to second centuries BCE); the Maze Cave consisting of about 30 interconnected caves; the Bathtub Cave that served as an ancient bidet; the reconstructed agricultural site with olive and grape presses and a wheat-threshing floor; a partially reconstructed Hellenist villa; a Crusader fortress; a Roman amphitheater for gladiator fights; and the Polish Cave, a small cistern and dovecote where visiting Polish soldiers carved an inscription in 1943.

There was a five-year effort by the Foreign Ministry, Nature and Parks Authority and Israeli World Heritage Committee behind the designation of Beit Guvrin-Maresha as a World Heritage Site. Other Israeli sites already listed by UNESCO are Tel Aviv-White City, Masada, the Biblical Tels, the Incense Route, the Baha’i Holy Shrines in Haifa, the Old City of Acre and the Nahal Me’arot Nature Reserve.

Click here for more on Beit Guvrin-Maresha.

For more about Israeli caves, click here.

Fighting for Israel's truth

We cover what makes life in Israel so special — it's people. A non-profit organization, ISRAEL21c's team of journalists are committed to telling stories that humanize Israelis and show their positive impact on our world. You can bring these stories to life by making a donation of $6/month.