Afnan Abu Taha doesn’t want her two daughters feeling alienated from their Jewish peers as she did when growing up in an Arab village. She doesn’t want them to struggle with Hebrew as she did in college. Neither does she want them to lose their own identity, language, heritage and culture.

So she and her husband sent their girls to the Hagar School, the only Israeli public school in the Negev providing bilingual multicultural education.

Hagar is in Beersheva, close to the Abu Taha home in suburban Omer.

“I want my daughters to speak Hebrew fluently and to have Jewish friends and to feel we can live together and do things together for a peaceful future,” she tells ISRAEL21c in English, a language all Israeli schoolchildren study.

Hagar began in 2007 with a single kindergarten and now has 330 children from kindergarten to sixth grade. Administrators do some creative calendar juggling to provide the requisite number of instruction days despite closing for major Jewish, Muslim and Christian holidays.

“When you hear the song played to signal the start of recess — alternating between an Arabic song and a Hebrew song — the children tear outside and play together and you can’t tell the difference between them,” says Hagar Executive Director Sam Shube.

Shube previously headed Hand in Hand Center for Jewish-Arab Bilingual Education in Israel, Israel’s only network of bilingual schools.

It was founded in 1998 around a nucleus of 20 graduates of the mixed kindergarten at the International YMCA in Jerusalem. The Jerusalem Hand in Hand is the largest, now encompassing about 700 students in K-12.

Hand in Hand subsequently opened locations in the Galilee, Haifa district, Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Kfar Saba/Tira and Kfar Qara (which may be the only instance in Israel where Jewish kids go to school in an Arab village). Two additional branches are planned, says Gaby Goldman, Hand in Hand director of communications.

“In the past five years we’ve had a steady growth of about 15 percent. In the 2017-18 school year our total enrollment was 1,750 and we have at least 100 more this year. Even more impressive is the demand — 1,200 students on waiting lists all over the country,” Goldman tells ISRAEL21c. “We have about 10 communities that want us to help them open a new kindergarten or school. This is how new locations start.”

Recently, Hand in Hand cofounder Lee Gordon received the Brock International Prize in Education.

Hand in Hand operates under the aegis of the Education Ministry and adds curricular material in language, historical narratives and religious heritage. Hebrew-speaking and Arabic-speaking co-teachers are frank about their divergent views on issues, modeling the ability to agree to disagree, says Goldman.

Parents, family members and activists form organized communities at each Hand in Hand school, holding activities such as dialogues and outings supported by USAID (the United States Agency for International Development).

“It’s not fair to put the responsibility of shared living only on the children,” explains Goldman.

Shared living is a difficult goal to accomplish, especially as children grow older and more politically aware.

“We don’t live in a Disney movie,” says Goldman. “We live in a place where families may have been hurt by aspects of the conflict. Hand in Hand is not a bubble; it’s a greenhouse and we nurture those little plants to become stronger trees.”

Vicky Makhoul entered Hand in Hand Jerusalem at age four and graduated in 2017. While cousins in her Christian Arab family “tend to stay with their Arab friends in their comfort zone,” the trilingual Makhoul says “people from our school go out into the real world and make friends with those different from them.”

Had she attended a typical Arab school or Jewish school, she muses, “I’d be a different person in my ideology. I think I’d only know one side of the story and I would not be open to hearing the other side,” though she admits views from the other side sometimes can be difficult to hear.

Makhoul tells ISRAEL21c that only in her senior year did she begin fully appreciating how the school not only helped shape her identity but also her opportunities. “When you speak three languages fluently, more doors will be open for you,” she says.

Worthy of respect

Shube says Hand in Hand gladly provided guidance to the founders of the Hagar School as they worked to establish the independent institution in Beersheva, a multicultural city of about 215,000.

“We see that children from Hagar grow up with a very sophisticated perspective on what democratic society means,” says Shube. “Children go back to their own social circles at home with a more nuanced view of who they are. They are less susceptible to the ‘us against them’ attitude.”

Abu Taha says her girls, now in grades seven and five, have an appreciation of their own and their friends’ cultures and holidays.

“They deal very well in all situations. They get along well with their cousins in Arabic and when we’re with friends who speak Hebrew they also do very well. They know about their identity even better than children in the Arab schools because of the differences between them and their friends,” she says.

Ehud Zion Waldoks, father of a third-grader and a first-grader, agrees. “Hagar doesn’t try to say that everybody is the same. There are very clear distinctions between who is Jewish, who is Arab, who is Christian, who is Muslim. They just try to impart that everyone and their traditions are worthy of respect.”

The Zion Waldoks kids are among the few students from religious Jewish families. Their parents supplement their religious education at home because Hagar’s curriculum does not include prayer or Bible study. They keep their kids in the school because its values are important to them.

“At that age it can be very formative to really understand that Israel is not just Jews, that Arabs are not ‘them’ and everybody can coexist naturally as people,” Zion Waldoks says.

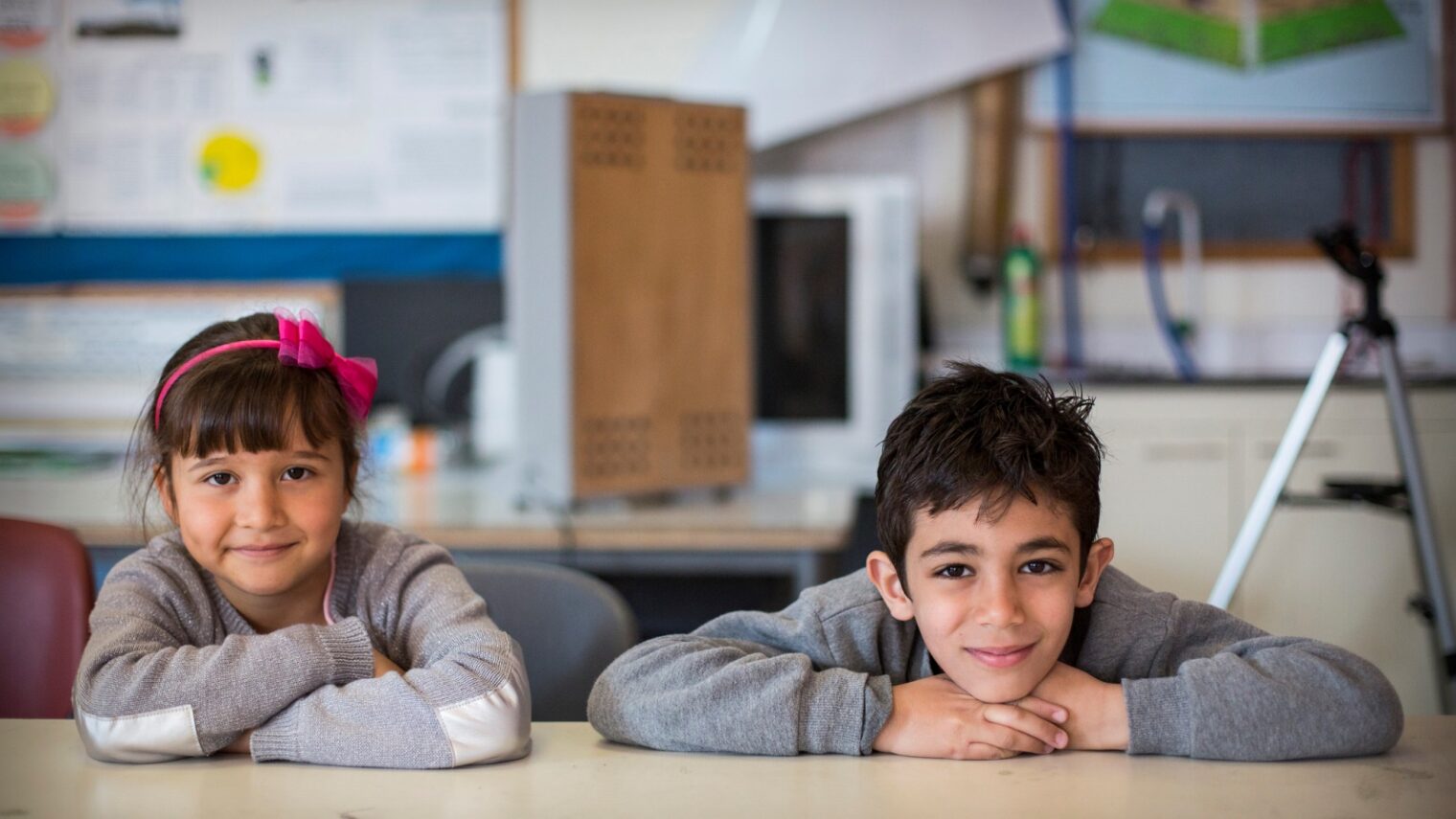

Below is a short documentary about the families of an Arab student and a Jewish student at Hagar, made by film students from Spectrum 360, a New Jersey educational institute for people on the autism spectrum.